A transplant to the Bay Area in the mid-2000s, Adam Mansbach received his early musical education as a kid in the Boston area, obsessed with hip-hop. Like many caught up in hip-hop’s tidal surge across the U.S. in the 1980s, Adam was inspired to MC and DJ, but he also found a calling in writing as a journalist and novelist. While still a college student in the mid-90s, he started the hip-hop journal/magazine, Elementary, before launching himself as an author. Best known for his profane children’s book, Go the Fuck To Sleep (2011), Adam has written over a dozen literary novels, YA books, humor books, and genre fiction, with his latest novel, The Golem of Brooklyn, published in the fall of 2023.

Adam and I met when he first moved to the Bay Area, and since then, I’ve had as many conversations with him about records as anyone I know. Every so often, I’ll get a random text from Adam, usually accompanied by a phone pic of an LP cover: “Yoo, you know this? Any good?” Over the years, we’ve debated the ethos of digging in terms of how much one should ever pay for a record or whether condition really matters to DJs. Our conversation this time dips back to how he got started digging through dollar bins for records to rhyme over, to going on the road with drummer Elvin Jones, to maxing and relaxing at home in front of his custom record cabinetry.

“I wasn’t much of a record thief, but I definitely ran with cats who had mastered the art of stealing records, so that was occasionally part of the program.”

Adam Mansbach Tweet

What’s your earliest memory of being interested in records?

My parents had records, but there wasn’t a working turntable in the house. So the memory had to be hip-hop-related, like catching Jam Master Jay behind Run DMC, going back and forth on records. It would have been around ’85 or something. Pretty quickly after that, I set about saving money to buy turntables.

Elvin Jones – Coalition. “This album is one of many excellent post-Coltrane outings, where Elvin is figuring out how to achieve the sound he wants: a flute, a bassist who can keep up, a muscular tenor, and a percussionist who contributes while still letting Elvin handle the business of polyrhythm unimpeded. I was Elvin’s drum tech and roadie for 7 years. From 1997 to his death in 2004, not a year went by that I didn’t spend weeks on the road with him. I got to know Elvin and his wife Keiko very well, both of whom were tremendously profound influences on me. For 2 or 3 hours a night, everybody else was on stage and I was backstage with Keiko, hearing her tell stories, and drinking tea. Keikio wrote a beautiful tune called ‘Shinjitu,’ which Elvin played a lot during my time with the band.”

What kinds of records were you buying back then?

By ’88, I was 12-13 and actively seeking out records I could rhyme over because I was primarily an MC. Some of the earliest records I bought were the Simon Harris breakbeat records. They were just loops—his loops—of things like the “Amen, Brother” break and sound effects at the end. I remember buying a copy of the Herbie Hancock Headhunters album and rhyming over “Chameleon” and “Watermelon Man,” stuff like that. It was very utility-based, buying shit that I could that I could rhyme over and make a basement demo tape.

I started high school in 1990 and was around a crew of kids whose parents had real record collections, some of whom had the Ensoniq Mirage and ASR 10. My world really opened up, and I was going to record stores in Boston, looking for breaks, funky records, hip-hop albums, and 12-inches on vinyl, under the tutelage of these older kids. I remember spending an entire weekend recreating the Das EFX “Mic Checka” beat. That would have been like ’92. We’re sitting around, “we got the drums, we got the loop, let’s see if we can exactly recreate the beat.”

At that time, I was a big fan of the stuff Boogie Down Productions was putting out. I’d probably say Criminal Minded is my favorite hip hop album of all time, or, you know, the greatest hip hop album of all time. It was so rugged, powerful, and unexpected when it came out. “I’m Still #1” bridged the gap between BDP’s second and third albums. The A-side, “Jack of Spades,” was dope; it was in the movie I’m Gonna Get You Sucka and got a lot of run. But the b-side, “I’m Still #1,” was tremendous.

By the late ‘90s, I was way into MF DOOM because I knew him from KMD. If I had the liberty to do a documentary on anybody in hip hop, it would be DOOM: the story, the reinvention, the tragedy, all of it is just very poignant to me.

Boogie Down Productions – Criminal Minded, “Jack of Spades.” “I’d probably say Criminal Minded is the greatest hip-hop album of all time. It was so rugged, powerful, and unexpected when it came out. Even the album cover, it’s poorly lit, it looks mad low budget but the dudes are holding fucking grenades and ammo belts. KRS One rhyming his ass off like nobody else in hip-hop, declaring that he was a poet, flipping into Patois to tell a story about shooting up drug dens and then escaping in a BMW with his DJ. It was ill on every level.”

Boogie Down Productions – “I’m Still #1.” “This 12-inch bridged the gap between BDP’s second and third albums. The A-side, ‘Jack of Spades,’ was dope; it was in the movie I’m Gonna Git You Sucka and got a lot of runs. The B-side, ‘I’m Still #1’ was tremendous. It was a remix for a song that had already been out for a year, but it was a total reimagining, not just a different beat but with new lyrics too. It was the most original remix I’d ever heard. I used to run it back again and again. It was so masterful and one of my earliest experiences with a remix, as something that was in dialogue with the original.”

“If it's got multiple percussionists, that's a good sign. If it's got a string section, that's a bad sign. If it’s after 1975, it’s going to be questionable, but if it’s ’69 to ’74, it’s probably going to be dope. You just start figuring all this stuff out.”

Adam Mansbach Tweet

MF DOOM Mask. “Zev Love X of the group, KMD, disappeared for a few years after experiencing multiple tragedies and setbacks in his life. He re-emerged as the masked supervillain, MF DOOM, wearing a mask like this one. It was a legendary second act as an MC and producer, and the mask was a key; he never took it off in public once it was on. This was a gift from J Period. He knows that I’m a big DOOM head. I always felt a personal connection to DOOM because I know so many people in his orbit, and I have heard a lot of stories about him from KEO over the years. DOOM was sleeping on his when he was recording, and KEO made the original mask. If I had the liberty to do a documentary on anybody in hip hop, it would be DOOM: the story, the reinvention, the tragedy, all of it is just very poignant to me.”

What was the Boston record scene like in the early 1990s?

It centered initially on a particular area in the Back Bay, around Newbury Street, where four or five record stores were within walking distance of the T stop. There was Tower Records, Looney Tunes, Mystery Train, Planet Records, and Biscuitheads Records.

I was very broke, so I deliberated thoughtfully about what I bought and passed on. Some of these stores did these grab bags where you get 10 records for $1 in a sealed bag you couldn’t look into. It was always a scam, I fell for that maybe once or twice, but it was also a path towards racking records because you could buy one of those and then linger in the store and switch a couple out. I wasn’t much of a record thief, but I definitely ran with cats who had mastered the art of stealing records, so that was occasionally part of the program.

How or who were you learning about records from, especially as someone who had to be deliberate in what you bought?

I was learning alongside a good friend, Eugene Cho, who lived around the corner from me and was a budding musician then and a professional musician now. We would dig together and make tapes. He and another two friends, Eli Epstein and Chiwale Shannon, we put our heads together to figure out what labels we should be looking for, what instrumentation is going to yield some funky shit, the names of drummers and bass players, what years the good records arefrom. Like, if it’s got multiple percussionists, that’s a good sign. If it’s got a string section, that’s a bad sign. If it’s after 1975, it’s going to be questionable, but if it’s ’69 to ’74, it’s probably going to be dope. You just start figuring all this stuff out.

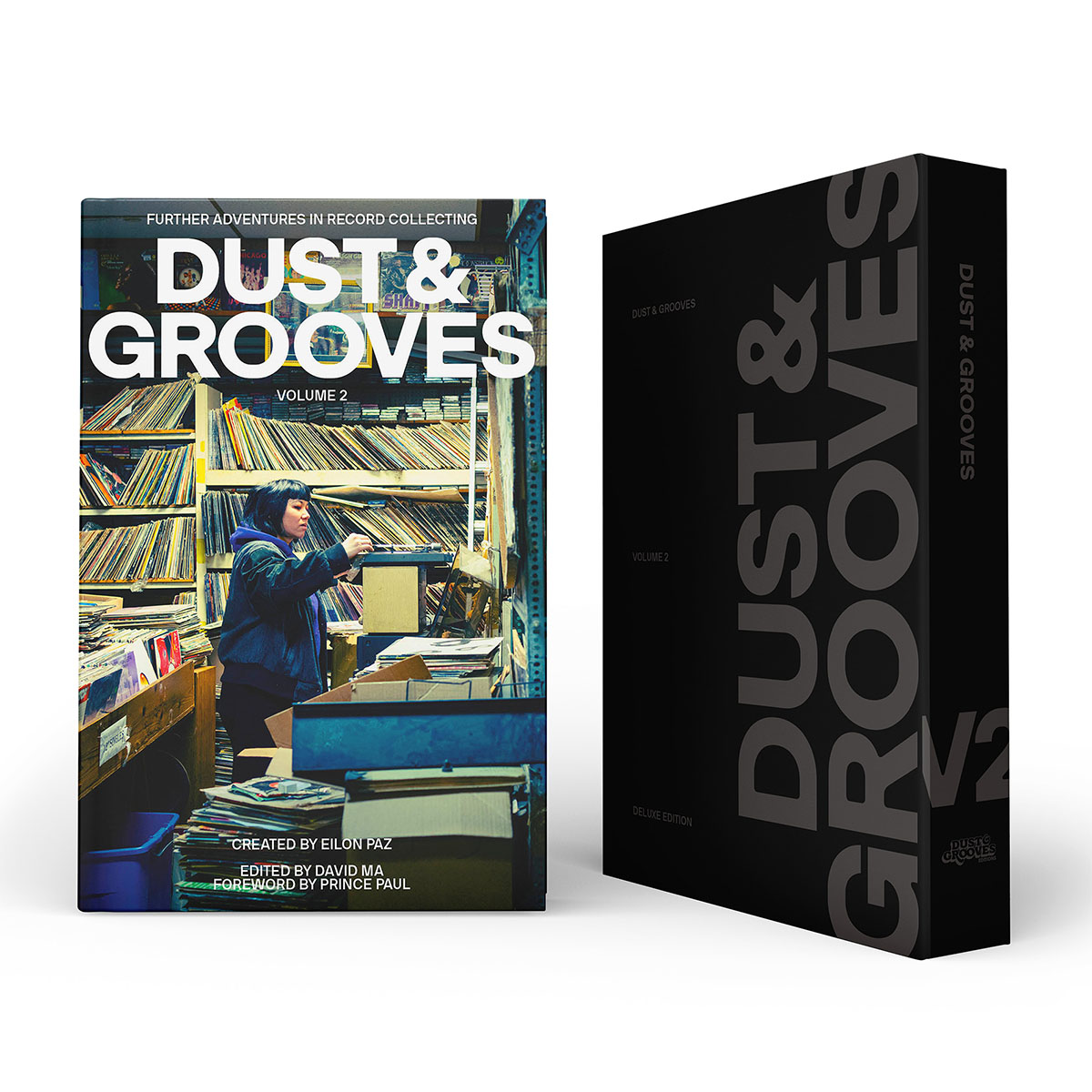

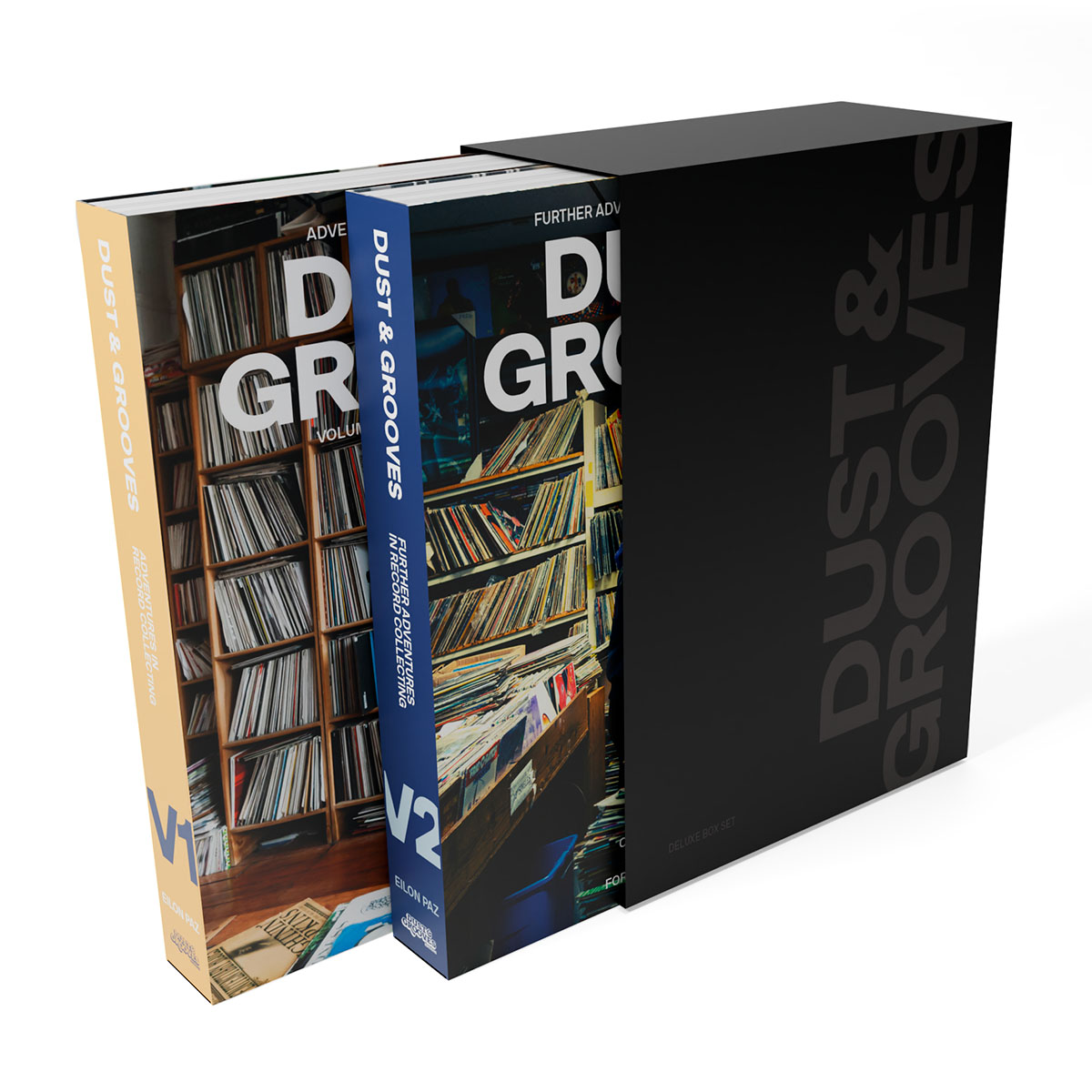

Further Adventures in Record Collecting

Dust & Grooves Vol. 2

Adam Mansbach and 150 other collectors are featured in the book Dust & Grooves Vol 2: Further Adventures in Record Collecting.

The Heath Brothers – Marchin’ On! Strata-East was one of those record labels where musicians got to stretch out and do their thing. They’ll be interesting and adventurous. This album is mostly known because Q-Tip sampled it for ‘One Love’ by Nas, but the entire four-part ‘Smilin’ Billy Suite’ is incredible and dedicated to drummer Billy Higgins. To me, the Heath brothers are one of jazz’s most important families. I’ve met the brothers over the years, with Elvin. I like Jimmy’s individual work. I really like Tootie Heath as a drummer. Stanley Cowell, Billy Higgins, these guys all orbit the same legacy jazz world that Elvin was a part of, so I feel a sense of connection. I went to see Tootie at the Blue Note in 2014 or ‘15. I stayed afterward, I wanted to just say hello. The set ended, and Tootie, who was probably 85, immediately made a beeline to chat up two women in their mid-50s. I was now this fucking weirdo standing there waiting for him to be done. So I bounced.”

After high school, you moved to New York City, and while Boston was hardly a cow town, I imagine being in NYC in the 1990s must have been an incredible experience.

I definitely was in the downtown stores: A-1, Gimme Gimme, Jammyland, Sound Library, all those Manhattan spots. I wasn’t really digging in the outer boroughs. Those were very fruitful times when I started to gain an understanding of the landscape of record culture and digging culture. New York stores were totally different from the Boston stores. None of the Boston stores were owned by anybody with a foothold in hip-hop culture or who understood what the young guys in the store might be digging. They were crusty old jazz, rock dudes. New York stores were from-and-of the culture, which was a mixed blessing because those guys weren’t sleeping on anything.

“Bro, you see me down here on my fucking hands and knees in the dollar crate? Stop handing me $60 records.”

Adam Mansbach Tweet

We have to talk about Elementary because early in your New York years, you started up this magazine/journal, which, I think, might have been the first time I became aware of your byline.

I got to New York City in 1994 as a Columbia University student. In the fall of 1995, author Tricia Rose was teaching a hip-hop course at NYU, the first time she taught this class. And I knew Tricia because she had recently married a very old friend of mine, Andre Willis. She invited me to come down to NYU and audit the class and it was fucking brilliant.

I met Alan Ket, who was about to put out the first issue of Stress Magazine. He was a graffiti writer from Queens, and he and I started connecting immediately in the front row. Martín Perna from Antibalas, now a very dear friend of mine, was in that class. Siah, of Siah and Yeshua Da PoEd, who were soon to release a record on Fondle ‘Em, was in that class.

I had the conviction that there were incredibly important and high-level conversations about hip-hop to be had that connected forces outside of the culture and challenged it; however, they weren’t happening in the pages of the hip-hop media as it was currently constructed. I had grown up reading The Source, but by this time, it had kind of fallen off. There were some indie magazines, but they didn’t include the conversations I wanted to have.

So, at the age of 19, with my only journalistic experience being running my high school newspaper, I just decided fuck it, I’m starting this magazine. Ket was like, “I published one magazine…I’ll publish two magazines.” I didn’t know shit about running a magazine but I knew what I wanted in it and I knew how to reach out to the writers I wanted. I called Upski — he had just published Bomb The Suburbs — got him to write for me. I convinced Joan Morgan to let us reprint something from When Chickenheads Come Home To Roost. Gave Jon Caramanica his first assignment ever.

My faculty advisor was Ann Douglas who was super hip and super into what I was doing and super willing to give me three courses worth of independent study every semester for the next two years so I can fucking run this magazine. That’s Elementary.

Elementary Magazine. “Elementary was the hip-hop magazine/journal I started while I was a student at Columbia University. The idea was to expand the conversation by putting hip-hop thinkers in dialogue with jazz artists, academics, and public intellectuals. I marched up and down Manhattan, hand-selling magazines to newsstands, hustling for ads. I threw parties to raise the money to go to print. We got Jeru to write his essay for the cover story. That portrait of Jeru is an oil painting done by Matt Doo, rest in peace. It was a bugged-out adventure to be running a magazine.”

Jimmy Smith – Root Down. “Jimmy Smith was always a monster on the B3, and he was always funky. A lot of organ players are, because of the unique place that the instrument holds in the culture. In 1997, I met DJ Force in Dubrovnik, Croatia. He had an encyclopedia of hip-hop that he was writing just for himself, just a loose-leaf binder, where he wrote down the names of every member of a given group and all their albums. He gave me this record, which I proceeded to carry around in my fucking backpack for the next six weeks as I toured the country. I don’t know how that shit survived intact.”

How did you end up working with jazz drummer Elvin Jones? You were his roadie for quite a number of years, right?

I started working for Elvin in 1997 when I was still a college student. I got the job via overlapping connections to the band. So when the opening emerged, they needed a roadie, and I got a shot. It didn’t involve any knowledge of the drums; it mostly involved being personable enough that people wanted to spend time with you.

You were already into digging for jazz records before this, so I’m wondering if your many years working with Elvin influenced your taste in records at all?

It challenged some of my assumptions about who or what was hip. One time, we were in Oslo, and Elvin walked right up to someone having lunch, lifted him off his feet in a bear hug. It was Dave Brubeck. From a record digger’s perspective, you might be inclined to flip past his records without giving them a second thought, but seeing Elvin’s respect for Brubeck made me think of him in a different light.

Also, for a lot of hip-hop-oriented diggers, you’re looking for the funky shit and the drum breaks… talking to these musicians who I knew only for the two funky records they made, gave me an appreciation for a lot of those guys, those records are like an aberration: they were chasing a trend or they got a big budget to do it. But it wasn’t an evolution into that [style], it was a money grab or departure. Nine times out of ten, they went back to playing bebop or straight-ahead music.

“If Kool and the Gang had been a bunch of West Indian dudes living in London, Cymande is what it would have sounded like.”

Adam Mansbach Tweet

You obviously have a long, deep relationship with jazz music and jazz artists. Who are some of your favorites?

One name that comes to mind is Pharaoh Sanders. I owned Jewels of Thought, and I remember playing it really loud every Sunday morning in my apartment in Fort Greene. If my downstairs neighbor, who was also a DJ and a record head, didn’t hear it by 11 am, she might give me a call and be like, “Yo, when you playing that Pharaoh Sanders?”

I interviewed Pharoahe Monch and asked him about his biggest inspirations, and he immediately said Eugene McDaniels’ Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse. He is another guy whose sound is so important.

Lou Donaldson, and his album Hot Dog, also stands out. By this point in Donadson’s career, he was perhaps the king of the soul-jazz scene. On a lot of soul-jazz albums from guys like Sonny Stitt or Rusty Bryant, you’d often get one or two funky tracks, but also a straight-ahead one, and a ballad. Donaldson was putting out records that were all heat. If there were six tunes, five of them would be super funky.

Pharoah Sanders – Jewels of Thought. “This is like the crown jewel—no pun intended—in Pharoah’s entire discography. Every album in this run of Impulse records yielded something sublime. There are a handful of albums that constitute a spiritual experience. The tune on here, ‘Hum-Allah-Hum-Allah-Hum-Allah,’ with Leon Thomas on the vocals, is just a gorgeous, searching tune. I probably got this record in New York in the late ‘90s. I remember playing it really loud every Sunday morning in my apartment in Fort Greene. If my downstairs neighbor, who was also a DJ and a record head, didn’t hear it by 11 am, she might give me a call and be like, ‘Yo, when you playing that Pharaoh Sanders?’”

Lou Donaldson – Hot Dog. “By this point in Lou Donadson’s career, he was perhaps the king of the soul-jazz scene. On a lot of those albums from guys like Sonny Stitt or Rusty Bryant, you’d often get one or two funky tracks, but also a straight-ahead one, and a ballad. Donaldson was putting out records that were all heat. If there were six tunes, five of them would be super funky. I got a chance to interview Lou when he was probably in his 80s, and he was like the hippest grandfather you’d ever want to meet. You’ll notice the top two inches of the cover are missing, which is probably why it was $1 at A1 Records in 1996. It evokes memories of digging, that possibility that existed in record spots at that time in New York when you could find all manner of extremely fly shit in those dollar bins. I didn’t have a lot of money to spend on records. So at that time, dollar bins were not a matter of principle or being a thorough digger. It was a matter of not being able to afford anything up top.”

Eugene McDaniels – Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse. “This record has such a unique sound. It’s a very interesting case of a dude breaking out and just doing whatever the fuck he probably always wanted to do after like 20 years in the business. McDaniels was producing and arranging, making pretty conventional music. It’s his bugged-out political album. ‘I remember interviewing Pharoahe Monch and asking him who his biggest influences were, particularly around vocals, and he immediately said Eugene McDaniels and this album. I was like, ‘Oh, of course, I hear that in him.’”

You play out in the Bay Area now and then; what are some of the records you usually toss into the crate to spin later?

Gene Russell’s Talk To My Lady isn’t amongst the most sought after or interesting in the [Black Jazz] catalog, but there’s one joint on here, “Get Down.” I’ve been playing it at gigs and putting it on mixes for years.

If Kool and the Gang had been a bunch of West Indian dudes living in London, Cymande is what it would have sounded like. I love spinning their album Promised Heights.

Pieces of a Man has some of my favorite Gil Scott Heron songs on it. It’s got “Lady Day and John Coltrane” which is such a beautiful joint. The title track is also incredible. It’s a classic Flying Dutchman record with a super tight band, with Pretty Purdie on drums, I believe, and Hubert Laws on flute. This one hits from beginning to end.

“To me, a digger is somebody who is about the rewards of putting in the work, the idea that there's more joy to be had, not just getting the thing that you desire, but coming up on it.”

Adam Mansbach Tweet

Gene Russell – Talk To My Lady. “Everything on the Black Jazz label is guaranteed to be interesting. There’s at least one breakbeat-jazz joint on each record that’s worth the price of admission. This Gene Russell album isn’t the most sought-after or interesting in the catalog, but there’s one joint on here, ‘Get Down.’ I’ve been playing it at gigs and putting it on mixes for years.Early in college, I was digging in a shop in Waterville, Maine. I pulled a few things, and the owner was like, ‘I just bought a record collection from a local radio station.’ And I was like, ‘Word?’ All the records were categorized through this weird system of spraying some paint on it and then writing a number. For a collector rather than a digger, that would drive you insane but I don’t give a fuck. Anybody could look at this cover and know that this is some hip shit to buy. Nobody in their right mind turns down that cover with Gene Russell, sitting there with a big ass hat.”

Gil Scott Heron – Pieces of a Man. “Pieces of a Man has some of my favorite Gil songs on it. It’s got ‘Lady Day and John Coltrane’ which is such a beautiful joint. The title track is also incredible. It’s a classic Flying Dutchman record with a super tight band, with Pretty Purdie on drums, I believe, and Hubert Laws on flute. This one hits from beginning to end. I met Gil a few times, but the first time was a pretty wild experience. He was playing at the Regatta Bar in Cambridge, MA, near where I grew up. I was a senior in high school. I ran up to Gil as he was exiting the stage, I said some shit about how dope he was, and handed him a sheaf of poetry I had written, with my phone number at the top. He didn’t even break his stride, but he took the shit. At 12:30 that night, my parents’ landline rang, and it was Gil. I had a two-hour conversation with Gil Scott Heron that night.”

Bernard Wright – “Haboglabotribin’.” “It’s funny to me that Bernard Wright was, I think, a recent graduate of the Music and Art High School in New York when he made this, but then, of course, Dr. Dre sampled it. And it kind of became this G-funk record. It’s a great record, unique, and goofy. I’ve been doing a weekly residency at Victory Hall in San Francisco with Martin Perna, Mara Hruby, and a couple of other folks. We had a great time, and we played whatever we wanted. I threw this single on, and the restaurant started dancing. This woman started throwing money at me. I’m like, ‘Yo, ma’am, it’s seven o’clock on a Wednesday night.’”

Cymande – Promised Heights. “If Kool and the Gang had been a bunch of West Indian dudes living in London, Cymande is what it would have sounded like. They just had such a unique sound. It’s this deeply spiritual, funky, dubbed-out, ethereal, stretched-out sound. This is probably my favorite of their albums.”

One thing that you and I have talked about, for years, is the ethos of what you spend on records. And I’m not trying to say you’re “cheap,” but more than most people I know, you’ve always seemed to follow a code about not “overspending.” It’s not because you can’t afford them, but because you feel like there’s a principle to follow.

I remember going to A1 with D Butters, a New York City prep school kid, and he would just hand me these $30, $40, $50 records, “you got this? You got this?” I’d be like, “bro, you see me down here on my fucking hands and knees in the dollar crate? Stop handing me $60 records.”

To me, a digger is somebody who is about the rewards of putting in the work, the idea that there’s more joy to be had, not just getting the thing that you desire, but coming up on it. For me, it was born from initially not having money to spend on records. So initially, it was like “here’s this record I want, but I don’t want to pay this price, so I’m going to put it back, make a note of it, and wait until I see it again for cheaper.” That becomes a mind state, this value-for-money kind of proposition.

I’m not like this in any other aspect of my life. I’ll go to a restaurant and spend whatever on dinner. My children are in fucking private school. But do I want to pay $5 in shipping for one record? No, I do not. Will I buy a bunch of other records that I may or may not really want or need, so that I feel like I got over because the shipping was free? Yes, I will. Should I see a therapist about this? Probably.

“It’s those moments when you take a quantum leap, like ‘now I got some shit!’ I had a pretty good reggae collection. Now I have a great reggae collection.”

Adam Mansbach Tweet

Ok, so what’s one of your favorite “I came up!” stories?

In the early 2000s, I was on my way to Academy Records in Manhattan on 12th Street. There’s a woman just pulling up in front of the store with an SUV full of records to try and sell. Dude comes out of the store and starts going through the records, but buys nothing. Okay, maybe it’s garbage, but I’m like, “Hey, do you mind if I take a look?”

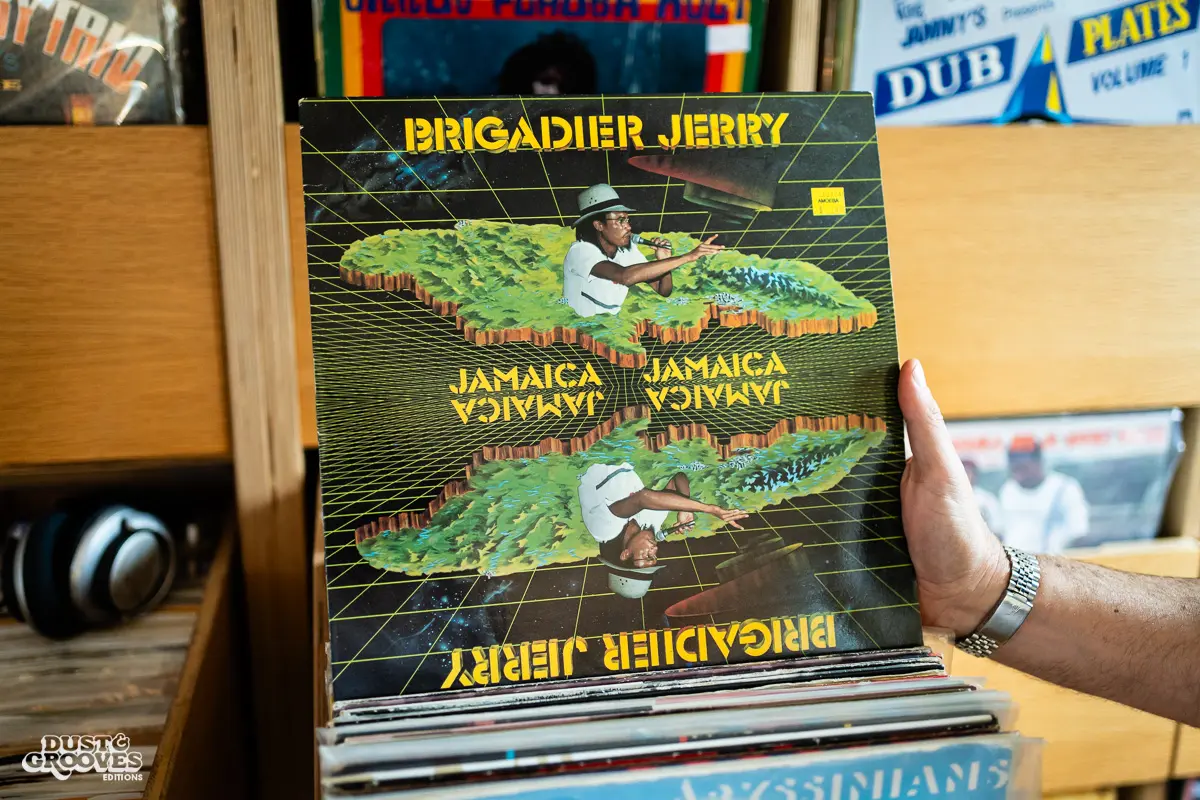

She had crates of reggae. This woman was Jamaican, had lived in the Bronx since the early ‘80s, and had been buying records steadily as they came out. Bronx, Brooklyn, Miami, Toronto, that’s where reggae records went and where the distribution was. She’s got incredible shit. Every Sugar Minott album from ’79 to ’87, every Barrington Levy record from that era, just tons of shit. $2 a record. I’m like, “You got more?” “Yeah, I got more at my crib. Do you want to come up and see?” I jumped in the car with her and drove up to her apartment in the Bronx.

I bought a lot and took a car back to Brooklyn with crates of reggae: the bedrock of my burgeoning reggae collection. It’s those moments when you take a quantum leap, like “now I got some shit!” I had a pretty good reggae collection. Now I have a great reggae collection.

Brigadier Jerry – Jamaica Jamaica. “Jerry is probably the most universally respected, and paradoxically, one of the least recorded guys in Jamaican music, because he was a sound system guy. He was killing shit, but there’s not much recorded output that reflects his genius. This is the only full-length album that captures him at his finest. I’m a huge fan of a ton of Jamaican music, but there’s a special place in my heart for the early ‘80s rub-a-dub sound when the toasting had achieved a level of sophistication and flow. They rhymed at a level that American MCs did not come close to in terms of flow. The melody, the improvisation, they were killing it.”

What got you interested in reggae to begin with?

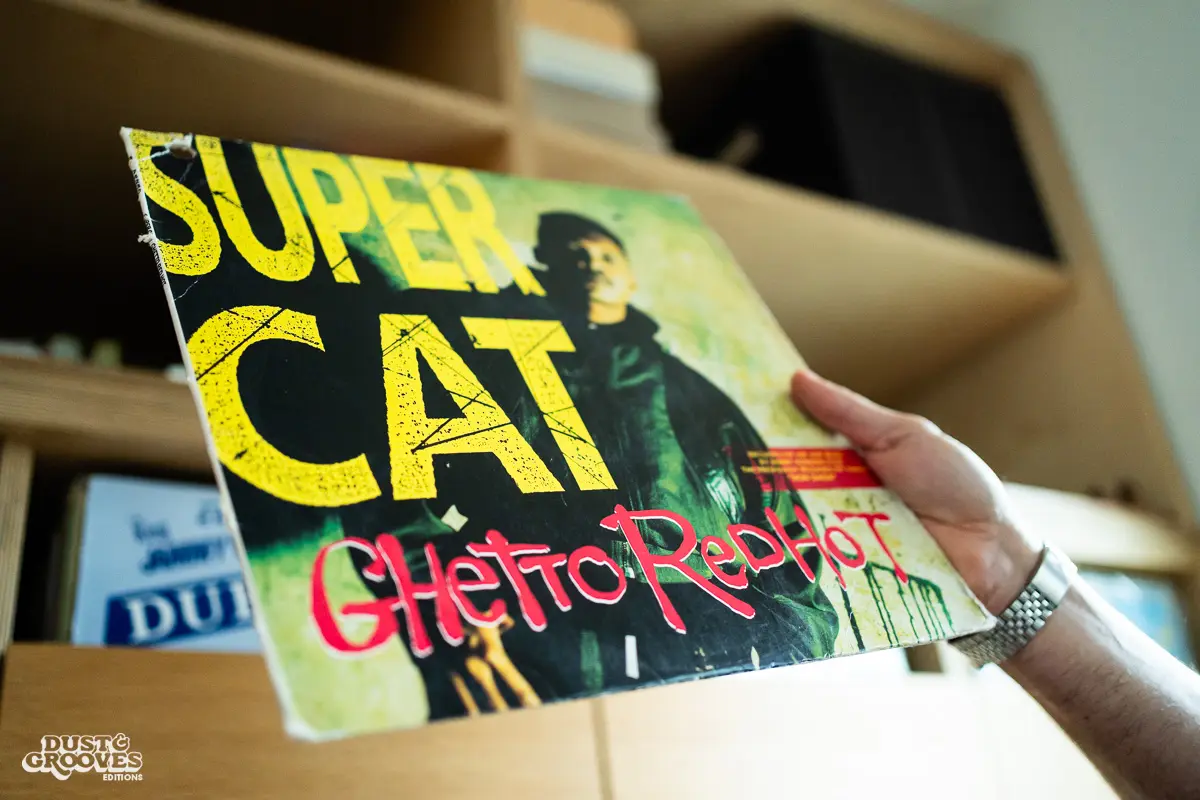

There were two pivotal moments. One was that early ‘90s moment when reggae was crossing over into hip-hop, when a bunch of early ‘90s dancehall artists were getting exposure with American record deals. Suddenly, Super Cat and Shabba Ranks were doing records with KRS-One and Heavy D on an American label, so their music was easy to find. I didn’t know much about it, but I dug it.

But really, when I moved to Brooklyn in 2000, that’s when I really got into reggae because it was just more ubiquitous. You heard it more, you heard it out, in your work, at stores. That’s when I started really buying reggae and educating myself, when I could walk to Beat Street and listen to 45s or buy a Barrington Levy’s greatest hits record.

Super Cat – “Ghetto Red Hot.” “‘Ghetto Red Hot/Don Dada’ was a monster 12-inch that completed Super Cat’s crossover from a Jamaican superstar to an international one. These songs were ubiquitous, and generations of DJs have copied Cat’s flow. Depending on how well they understand patois, American audiences who danced to Salaam Remi’s impeccable, Lou Donaldson-sampling ‘Ghetto Red Hot’ remix may have realized that it’s a deeply incisive commentary on political violence in Jamaica. Super Cat is one of my favorite artists of all time, and he is the greatest MC of his era. He’s one of the first reggae artists I became aware of when hip-hop and reggae were fusing. He embodies a lot of what I love about dancehall culture. That Salaam Remi remix of ‘Ghetto Red Hot,’ still bangs and it had the fucking clubs and the streets and everywhere else on smash.”

Who are some current artists whose music you ride for?

DJ Frane is a very dear and old friend of mine, and, for my money, one of the greatest DJs in the world. There’s so much technical proficiency, but also deep conceptual artistry. “Christmas At the Iceberg” is very special to me because it features my daughter, The Jazz Wolf, rhyming on the A-side.

Another group is Sault, one of the most interesting groups making music right now. They’re Black and British and maintained anonymity through a run of really original albums, each of which has its unique sound. Some are straight funk, some are disco, and some are Afrobeat. All of it feels essential and of the moment, while being very connected to the history of transatlantic Black music.

DJ Frane – “Christmas At the Iceberg.” “DJ Frane is a very dear and old friend of mine, and, for my money, one of the greatest DJs in the world. There’s so much technical proficiency, but also deep conceptual artistry. This record is very special to me because it features my daughter, The Jazz Wolf, rhyming on “Christmas At the Iceberg.” I think Frane originally hit me up to see if I wanted to drop a quick verse on it, but I was more invested in promoting my nine-year-old daughter’s rap career at the time. I wrote a verse for her, and she knocked it out into the studio. I’ve been rhyming for 30 years, and I have never been on a record, and my nine-year-old gets on wax before me. I’m tickled by the fact that this record exists. Just the fact that one of my friends and my daughter made a record together is amazing.”

Sault – Untitled (Black Is). “Sault is one of the most interesting groups making music right now. They’re Black and British and maintained anonymity through a run of really original albums, each of which has its unique sound. Some are straight funk, some are disco, and some are Afrobeat. All of it feels essential and of the moment, while being very connected to the history of transatlantic Black music. I think Cosmo Baker put me onto this. He’s a cheerleader for all the music he loves on Twitter and he’s never wrong about some shit that’s dope. This was in heavy rotation for me during the pandemic. Super interesting, conscious funk. They go in all kinds of different directions. Sometimes it’s more of a disco joint. Sometimes it’s an extended suite, like you don’t know what you’re gonna get with them.”

Ok, last question. A few years back, you decided to graduate from the same Ikea shelves all of us have owned at some point for records, and you had some beautiful custom shelves made for you. Technically, it’s the custom record drawers that make them especially notable. What’s the story behind those?

I found a local woodworker, a company called Oak and Wood, which is kind of a weird name in retrospect, since oak is wood. My initial thought was to build a more sturdy version of the IKEA cubes, but I always wanted a system where you can dig like it was a crate. They designed something that was just super fucking ill and super fucking expensive. They’re very deep; each drawer is two crates worth. They also built this custom shelf for the turntables that slides in and out. It spans the whole wall, so it’s visually striking and beautiful, but still intensely practical. It allows me to be meticulous in my categorization and know where the fuck everything is. I’ll never go back to cubes.

You’re very well connected across a whole swath of different people…who would you like to see featured in Dust & Grooves?

I’ve got a residency right now at Victory Hall in SF, so I’m talking records with my fellow DJs there every week, so I’d say all of them: Martín Perna, Mara Hruby, and Weyland Southon. Torrance Rogers and Dug Infinite are two other great DJs with great knowledge and stories.

Adam Mansbach is a New York Times best-selling author of the book Go the Fuck to Sleep. He has also written The Golem of Brooklyn and Rage is Back among others, and has a deep history as a music journalist.

Website

Further Adventures in Record Collecting

Dust & Grooves Vol. 2

Adam Mansbach and 150 other collectors are featured in the book Dust & Grooves Vol 2: Further Adventures in Record Collecting.

Become a member or make a donation

Support Dust & Grooves

Dear Dust & Groovers,

For over a decade, we’ve been dedicated to bringing you the stories, collections, and passion of vinyl record collectors from around the world. We’ve built a community that celebrates the art of record collecting and the love of music. We rely on the support of our readers and fellow music lovers like YOU!

If you enjoy our content and believe in our mission, please consider becoming a paid member or make a one time donation. Your support helps us continue to share these stories and preserve the culture we all cherish.

Thank you for being part of this incredible journey.

Groove on,

Eilon Paz and the Dust & Grooves team

2 Comments

Tony Smith

hey dust and grooves, this is major Don west, better known as Tony Smith! just wanted to say you guys are doing the damn thing totally, I am in love with vinyl collecting and anything else that goes along with it! you guy's only enhance the awesome feelings that go along with finding great records. you all keep bringing it, I love you cat's!!!!!!!!!!

Eilon

Dear Tony, Thank you !! You made our day :)))