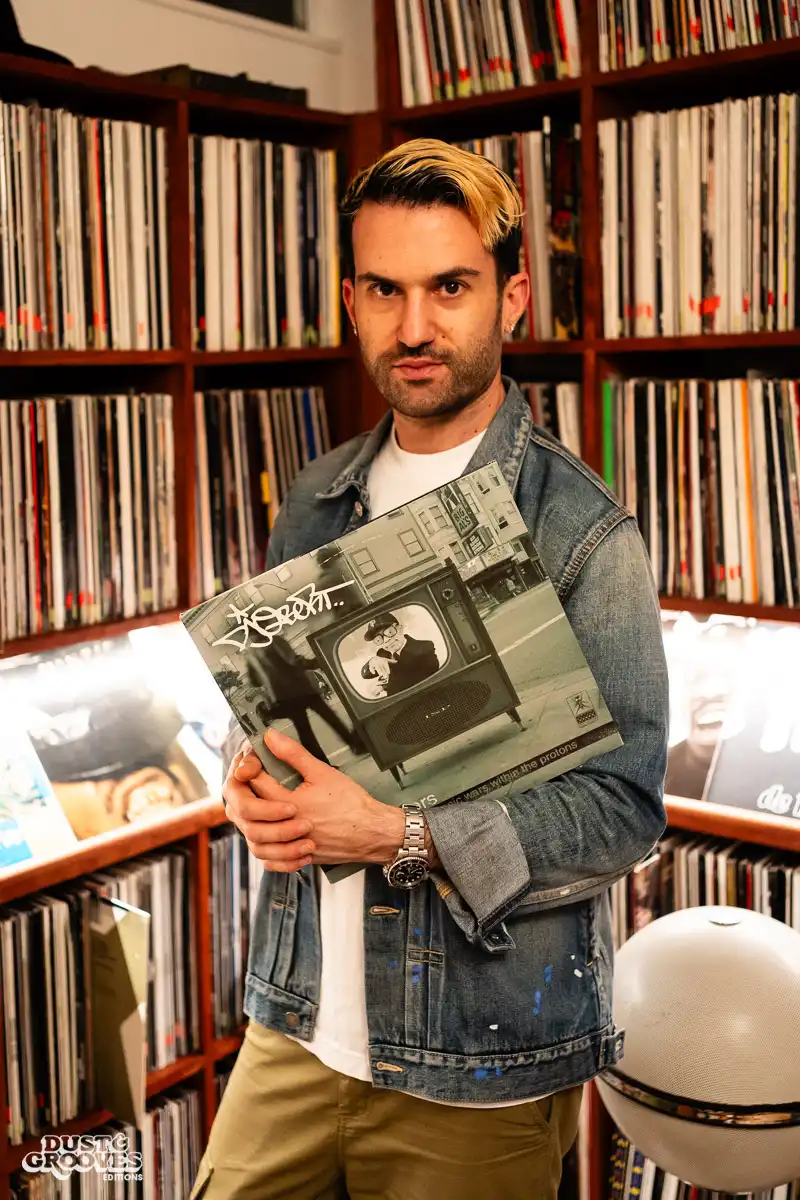

Smooth transitions are paramount in DJing, and few DJs have transitioned through the phases of their career as gracefully as A-Trak. He first rose to prominence as a turntablist wunderkind at the DMC World DJ Championship in 1997 at fifteen-years-old, founded his first record label Audio Research when he was still in his teens, and then became a tour DJ to the stars, such as Kanye West and John Legend, before diving headfirst into the world of house music and founding the influential label Fool’s Gold, all the while maintaining a hectic travel schedule and a thriving career as a recording artist, both solo and as an in-demand collaborator and producer.

Originally from Montreal, A-Trak was photographed with some significant records from his life and career in Los Angeles and spoke with us about them later from his studio in Brooklyn. For such a busy and successful person, he radiates a distinctly Canadian pleasantness. His love of music and reverence for other artists of many genres and mediums is readily apparent here, as he recounts his past as a battle DJ, significant mentorships, jazz fusion, and his gradual move toward the primal rhythm of house music.

“Most music that I make or play is digital, but I still think that records are irreplaceable”

A-Trak Tweet

You began your career quite young, as a battle DJ. How has your view on records and record collecting evolved since then?

It’s changed a lot; on a day-to-day basis, most music that I make or play is digital, but I still think that records are irreplaceable, and I think there’s something to the intangible charm of buying records, collecting records, or having records somewhere in your house.

Eilon came by my place and saw my record collection and, I would say three-quarters of the collection he saw and shot was in storage for years while I was traveling heavily. Eventually, I got to a point where I just missed having them around. I missed that feeling of having these generations of brilliant musicians, and even cover sleeve artists, close by.

During those years, all I had access to was what I was buying, as opposed to what I had previously accumulated. I would sometimes go to a friend’s house where they had their full collections, and I’d be like, “damn, I missed this.”

It’s not even that I needed any particular record, but just the thought of having those records on the shelves is reassuring; knowing that you could just walk over, and pull something at random summons all these memories. I could pull the record out, and right away I would remember when I bought this album, in the same haul as when I bought this other one, and I remember the joy that I got when I discovered something in the liner notes.

You’ve traveled quite a bit in your career. Do you make it a point to look for records when you travel?

Not always. My travel schedule is pretty fast-paced. A lot of times I’m rarely in a city for more than a day, and just staying on top of my work or dealing with emails and my label and planning for events I’m organizing, that kind of stuff. And then I go over the music for whatever set I’m playing that night, that takes up most of my time.

As much as I love the romance of digging, you know there are a lot of our friends and peers who get into the city and go straight to the record shop—I’d be fronting if I said that I’m that guy. Buying records is this thing that I’ll do in spurts. After some time, I miss it. I’ll be like, “I haven’t bought records in three months, that’s so weird. Let me go to the shop and buy a bunch of shit, or go online and grab a few things.”

I’m also fortunate to have friends who put out great records, and they send me their stuff. And, with all that combined, I try to keep the collection going.

Do you keep an archive of your own records? Do you make it a point to make sure you have copies of every 12-inch you put out, or, as an example, the 45 you did with Stone’s Throw when you were a kid?

Oh, yeah, definitely. And even a few extra copies to give to friends who come over. Right now, you’re talking to me at my Brooklyn studio and even here, which isn’t where I have the main collection, I have a little stash of my own records with extras for when friends come by.

I try to not be the guy that’s like, “let me go buy a copy of my own record from 10 years ago because I didn’t think to keep it.” Nothing wrong with it, but I always crack up at that. I do have pretty much everything I’ve put out myself.

Do you remember what your first record was? Did you steal your parents’ records? Or did you go out and buy your own?

It’s a combination of things. My parents had some records at home, not a very big collection, but two or three crates worth of favorites that they kept, and some sort of belt drive turntable. I got into music by hanging out with my older brother Dave, so a lot of my music discovery was from hanging around him and his friends—whatever they got into, I absorbed.

"I got into music by hanging out with my older brother Dave, so a lot of my music discovery was from hanging around him and his friends—whatever they got into, I absorbed.”

A-Trak Tweet

I started accumulating a few records, a combination of having a few of my dad’s records that I liked, stuff like Songs in the Key of Life, or whatever. And then Dave and I initially went to the shop together and bought a few things. At this time my brother was also getting interested in figuring out how to make beats. One of the first things that I remember buying together was a breakbeat record, just one of those producer tools that had drum loops. I also remember buying a break record that had the sample for Nas’s “One Love.”

It was something that was kind of a big event in my life, the first time that I went to the record store without my older brother at the age of 13 when I was starting to mess around, trying to scratch a bit. My brother and I had the cassette for Pete Rock & CL Smooth The Main Ingredient. So I went to the shop by myself and bought a single for “Take You There,” and that had an acapella. So that was really precious to me because I could try to scratch words, as opposed to just trying to figure out how to scratch on an entire piece of music.

Let’s talk about some of your records. Let’s begin with Jaco Pastorius’s Self-titled, a breakbeat classic. What can you tell us about that record?

That’s a record that, if you flip to it in the bins, you have to stop. If you see that record, you’ll be drawn to it. So, I remember that my brother and I got it early on, when we first started to buy old stuff and started to understand where samples came from—hip-hop was the gateway.

So you’re listening to hip-hop, and you have a vague sense that sampling is being used but there’s still the x-factor of “what are these records?” Because you go to a record shop and there are thousands of records. Which are the important ones?

The other thing is, as my brother and I were discovering music together, he was also learning the guitar, and he had a guitar teacher who was really into fusion, and who would show him Chick Corea type of records. So both of us developed a palette for jazz fusion early on.

The way I describe it is that you have nostalgia for something you’ve never actually heard. It just immediately evokes that feeling.

Yeah, totally. Like you yearn for this thing that you’re not even sure is out there.

“Donuts is given a lot of importance now, whereas, in real-time, it felt a little bit like a curveball or footnote. We didn't see that coming.”

A-Trak Tweet

Yeah, it’s great when it locks in. Can we talk a bit more about the Dilla Ruff Draft EP? You’ve said how his records were kind of hard to track down sometimes when they first came out. The releases were on different labels, and there were sometimes questions about the legitimacy of the pressings.

The whole Dilla thing is interesting because posthumously he became such a hero, and I’m glad he did. But I think a lot of the Dilla fandom now is a very different experience from the Dilla fandom when he was alive. Donuts is given a lot of importance now, whereas, in real-time, it felt a little bit like a curveball or footnote. We didn’t see that coming. If anything, I would say that Fantastic, Vol. 2, and Welcome 2 Detroit were probably the big monuments when he was alive.

But also, there was this sort of scavenger hunt of trying to seek out his records. There would be sort of hearsay about something that was coming out, but it was never through the same distributors, never through the same labels. Dan Charnas’s Dilla Time book explains the business reasons behind all that. But at the time it just felt like a scavenger hunt where you would hear that the next Busta Rhymes album would have some Dilla beats, and then as soon as it came out, you’d have to find it.

When Ruff Draft first came out, it was through the German distributor Groove Attack. One of the cool things about growing up in Montreal is that we got imports from overseas as much as we got stuff from the US, so a lot of stuff trickled in. Ruff Draft was just such a cool EP where every track felt experimental and futuristic. It felt like he was reinventing himself again and again. He was starting to reach many reinventions, which was really impressive.

“It was that time in the late ‘90s … when turntablists as a community proudly declared that we could perform and make records by ourselves…People used the phrase “art form” a lot in those years, and likened it to jazz; Q was very visionary.”

A-Trak Tweet

Let’s get into DJ Q-Bert Wave Twisters, a record where the artwork is inextricably tied to the music because it was also released as an animated movie. Such an impressive project, especially at that time.

It’s certainly one of the pinnacles of scratch music. The Skratch Piklz kind of gave me a cosign, brought me into the crew as what they called an Honorary Member, right around the same time that I won my first DMC championship. And it was this sort of gold star that I had on that meant a ton.

It was that time in the late ‘90s and approaching the millennium when turntablists as a community proudly declared that we could perform and make records by ourselves. We didn’t need to be paired with rappers. Within hip-hop, there was this branch of experimental, kind of trippy weirdos, and we could stand on our own feet. At the time, I would say Q-Bert and the Piklz were very vocal about that autonomy and the legitimacy of scratching as an art form. People used the phrase “art form” a lot in those years, and likened it to jazz; Q was very visionary. Comparing scratch DJs to Miles Davis and Jimi Hendrix and people like that, I don’t think hip-hop heads were thinking that broadly before that era.

When Q made Wave Twisters, it felt like a team effort to birth that. I think it’s important to credit the whole Skratch Piklz crew. Mix Master Mike produced a few of the beats and DJ Flair was on there, and I think his scratching styles were very influential. But Q was definitely the figurehead to sort of hatch the egg, in a sense. They created this sort of Yellow Submarine-esque accompanying animated album. It just felt so visionary. I think a lot of scratch DJs that followed Q looked at that like, “damn. I didn’t even realize we could do that.” There was a real vision there.

"My first foray into DJing was as a turntablist, and Q-Bert was the visionary leader of our scene. He brought scratching into psychedelia.”

A-Trak Tweet

“They created this Yellow Submarine-esque accompanying animated album. It felt so visionary.”

Did you want to make that kind of symphonic, multi-layered, scratch music yourself?

For sure. After my first championship, it felt like the natural next step was to either make a four-track mixtape, or some sort of scratch music project. But producing, in that sense, didn’t come to me right away. I would try, and I was kind of slow in my output, I remember it was frustrating for me at that time. And I ended up having the odd track here and there, like the Stones Throw 7-inch that you mentioned.

Also, prior to that, Peanut Butter Wolf was the A&R for a compilation for Strength magazine. I had a track on there, so I had little things here and there, but I never managed to actually make a full album in those years.

I suppose it shouldn’t come as a surprise that you grabbed an Armand Van Helden EP called 2 Future 4 U. When did you start to “get it” with house music, and how did you transition your sound out of hip-hop and into electronic music?

When that came out, it’s funny to think back that I was still strictly a hip-hop head. There were a couple of house tracks that had music videos that I would catch on TV. And some of them caught my ear when they were made with kind of a hip-hop aesthetic. If there was a Daft Punk video on TV or Armand’s “U Don’t Know Me,” or the odd Basement Jaxx video or song, some of that stuff would catch my ear, I thought it was cool. It didn’t feel cheesy to me without even fully clocking it, maybe because it was still made from samples and loops. And later on, I understood that it was made using the same equipment as the rap stuff I love. Whether it’s an MPC or an SP-1200, some of those samples kept the grit that I liked on my beat records.

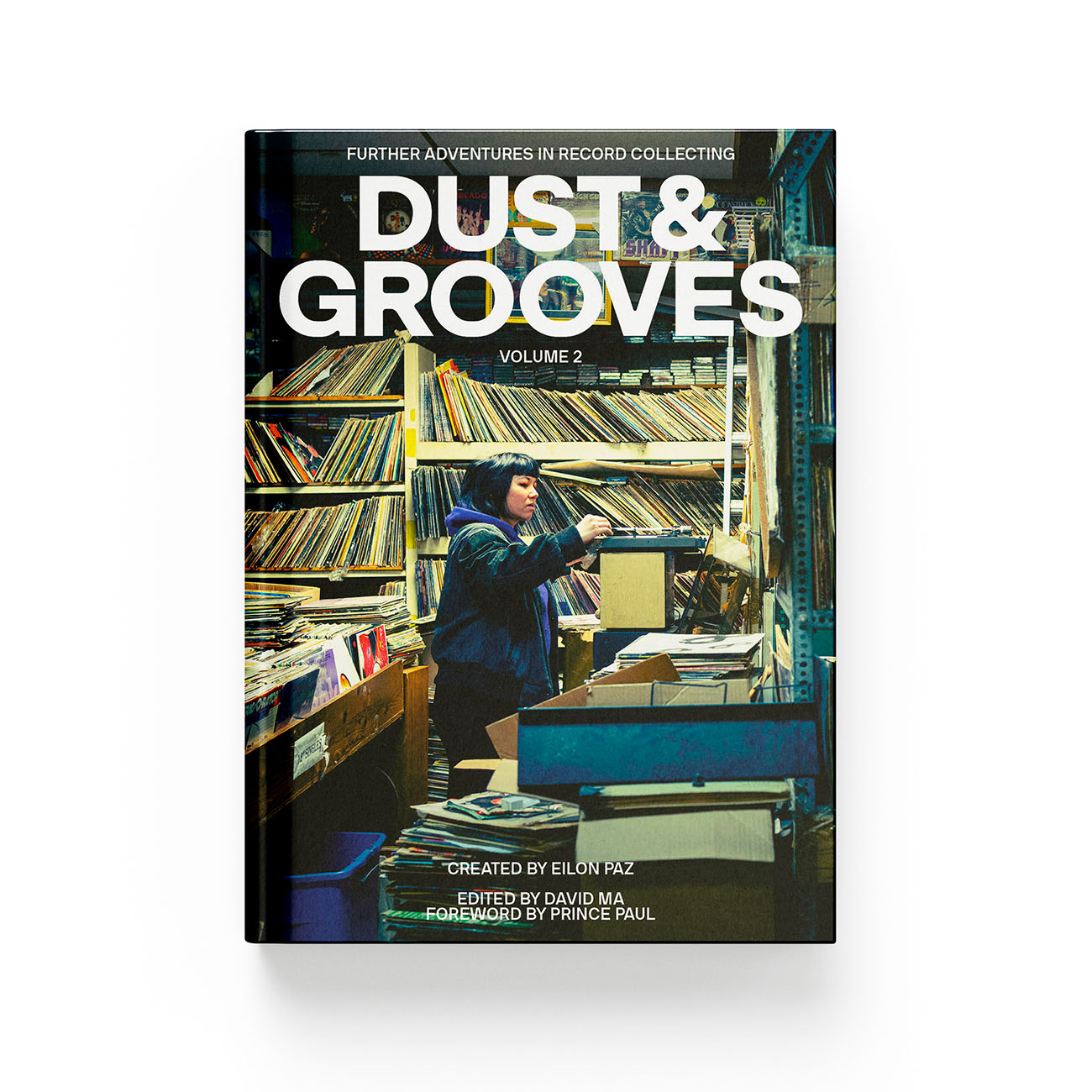

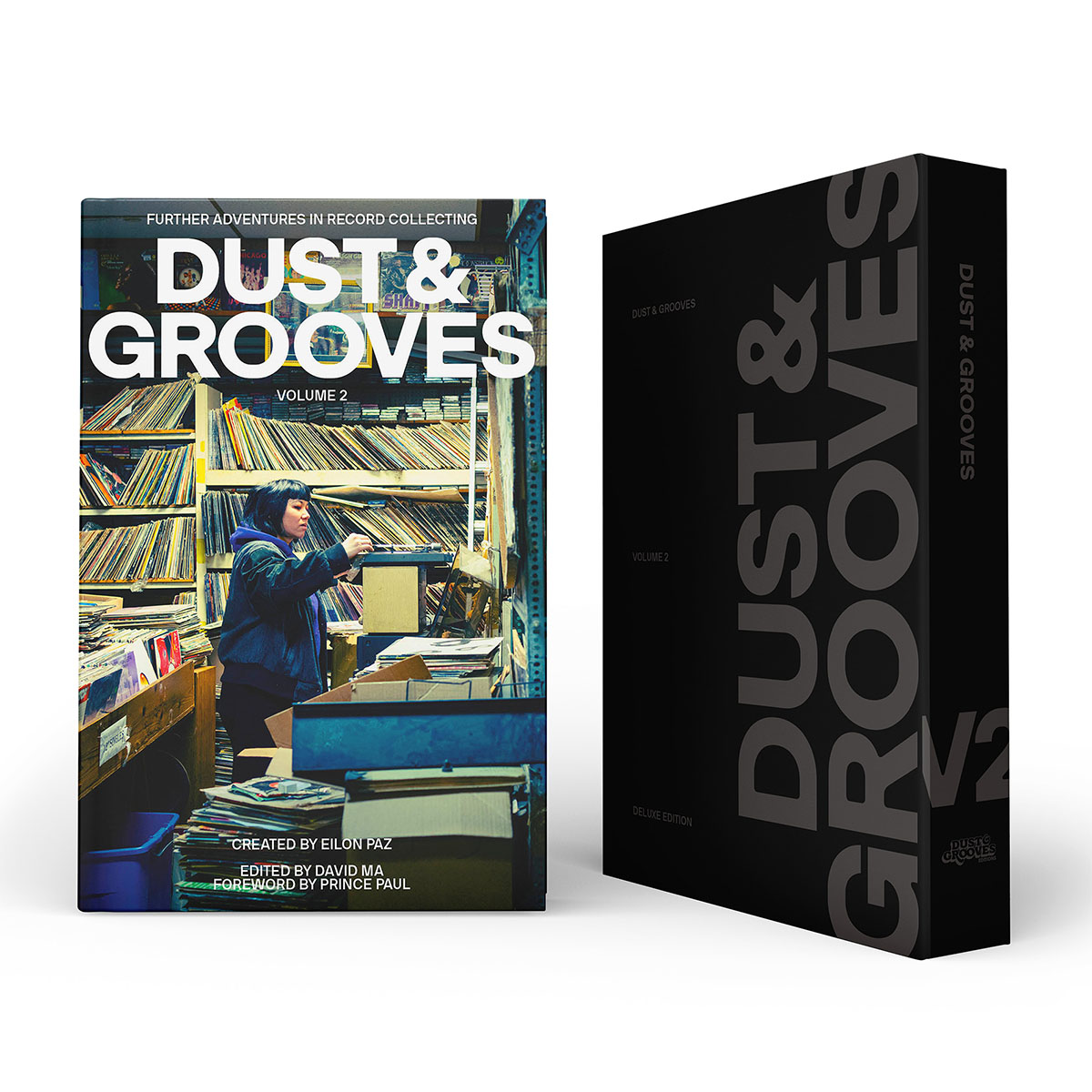

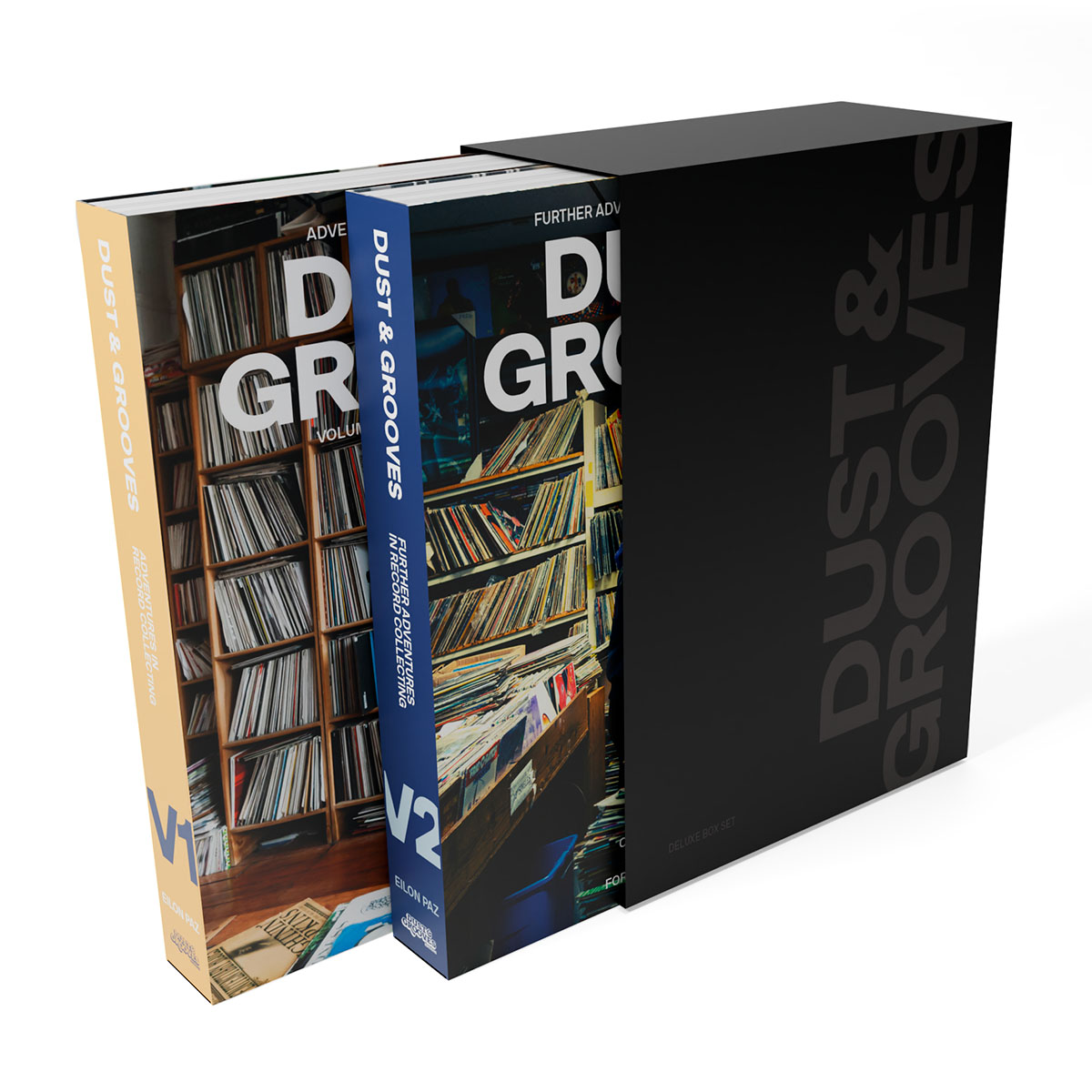

Further Adventures in Record Collecting

Dust & Grooves Vol. 2

A-Trak and 150 other collectors are featured in the book Dust & Grooves Vol 2: Further Adventures in Record Collecting.

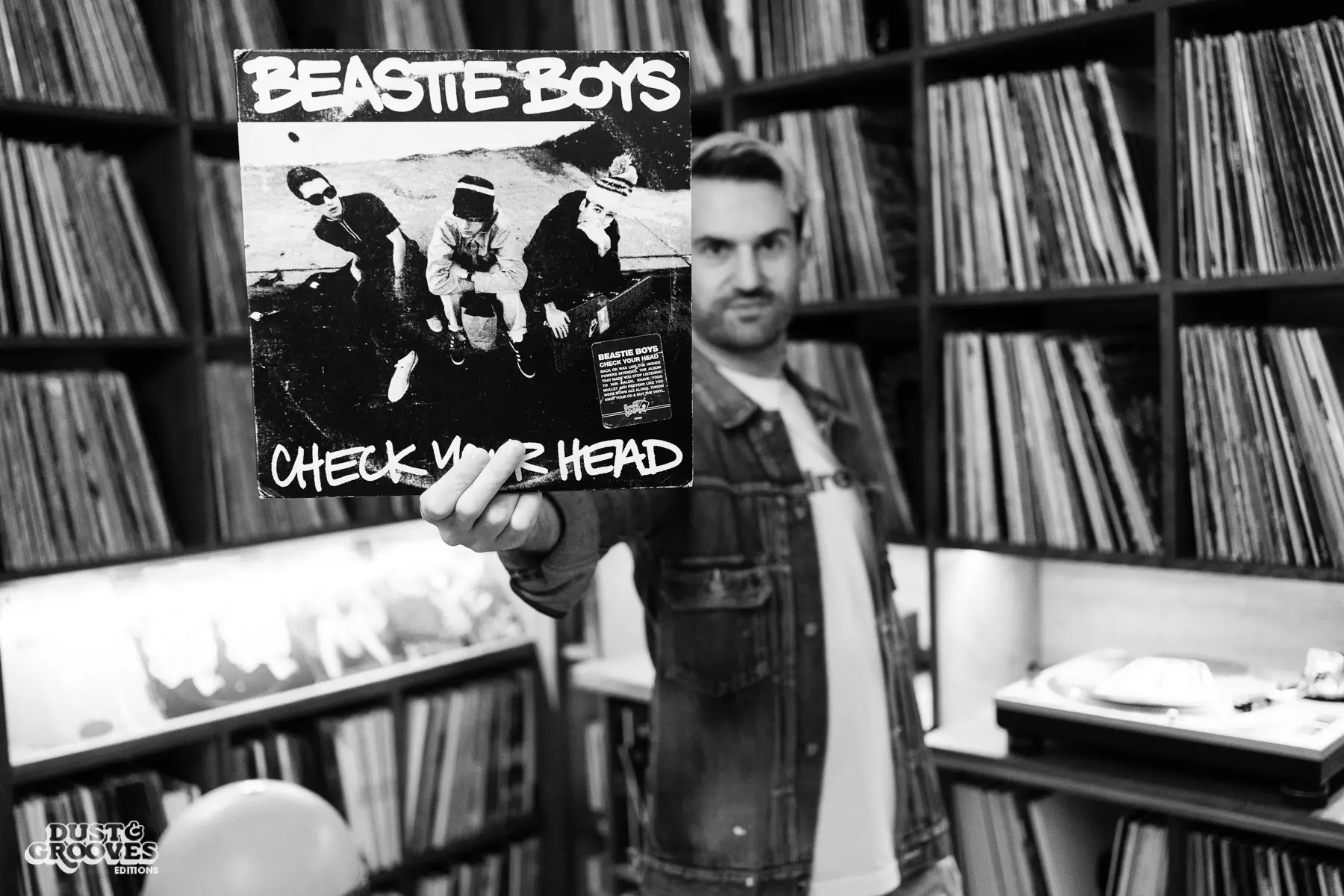

“I still try to dress like the 1992 Beasties. The photo collage in the gatefold album, which I first discovered as a cassette booklet, is still my mood board for life.”

A-Trak Tweet

Through the years, Armand became such an important figure in my life. Later on, we formed Duck Sauce, and we made a ton of records together. We’re still active now, but before meeting him, I was getting into house music, and I was getting familiarized with the full scope of this enormous catalog that he already had. It was sort of dawning on me that this guy might be the GOAT. You know what I was saying about Dilla, about the amount of reinventions? I would just hear all these eras of Armand tracks and remixes. In his case, he would have all these different aliases, too. Like, how does someone churn out so much music, how does someone have so many reinventions and just stay inspired over such a long time?

As for my timeline, I’d say that by around the mid-2000s, there were a few things that coincided that made me start to color outside the lines of hip-hop. The advent of Serato catalyzed some of this curiosity, because Serato came out in 2003, and suddenly, if I was curious about other sounds, I could link up with other DJs. We were all building up digital libraries of music, and I could link with another DJ and just swap hard drives for an afternoon and suddenly have an entirely new selection, an entirely new world to explore musically.

That was happening at a point in time when hip-hop was starting to feel a little stale or less exciting for a period of a few years. That sort of rut didn’t last that long, because then Kanye came along and there was all the great Just Blaze Roc-A-Fella stuff, and a bunch of others too. But there was a brief rut in hip-hop that made me look elsewhere, and the digital DJing transition made that curiosity yield a ton of new sounds in the music I had access to.

I feel like normal people were doing similar explorations with their iPods, similar to what DJs were doing with their hard drives. All of a sudden as a music fan you could spend zero dollars and get all these new songs and then see what you liked about them, and pick and choose and delete and swap them, and it changed everything.

Limewire, Napster, and mp3 blogs proliferated around the same time too. If you had that curiosity, you could download some ‘80s classics so I can have a little ‘80s party crate. You could just download stuff, which just wasn’t possible before.

“After a while, I honed in on the magic groove of house music that's tried, tested, and true. It’s almost like all roads lead to four on the floor.”

A-Trak Tweet

So the range of my DJing started to broaden. And I went from being just a hip-hop DJ to then getting into the eclectic thing of the early 2000s and mash-ups and then going into what we now call “Blog House,” which is a mid-2000s electronic hybrid production that was super broad, fruitful, and weird, but didn’t really fit in one category. After a few years of that form of eclecticism, I kind of just landed on house music, I think just from DJing, from playing out more up-tempo music.

After a while, I honed in on the magic groove of house music that’s tried, tested, and true. It’s almost like all roads lead to four on the floor.

You have a real gift for ending your answers on a poignant note. There’s another record here I’m not that familiar with, Al Di Meola’s Land of the Midnight Sun. What’s up with that record?

There’s more of a personal story there. It goes back to my pre-digging years of discovering stuff with my brother and his guitar teacher. So the same way that I mentioned that his guitar teacher was teaching him about jazz fusion records, there were also some Al Di Meola records that I remember my brother learning on the guitar before we fully dove into buying records as hip-hop kids. I remembered this record in the back of my head for a few years.

And then a couple years later, I’m DMC champion, the scratch kid, whatever. As scratching was evolving into this more experimental thing, I was searching for different things to do with scratch routines, even just for the purpose of participating in battles every year and needing to push my routines forward. I was thinking, “what can we do to push the envelope?” And then I had this idea to emulate a guitar solo with scratching.

I went back to this Al Di Meola song that I remember my brother learning with his guitar teacher years prior, pulling out this record and being like, “I wonder if I can play along to this, but with scratching.” And that’s why I picked that record. It’s just this experimental routine that I came up with for my own experience. I liked how it tied a loop between two periods of my life.

Biz Markie Biz’s Baddest Beats. A great compilation of Biz Markie’s early work, with one of the most iconic covers in hip-hop. It’s feel-good music. Tell us about your history with the Biz.

Biz Markie, rest in peace. What a larger-than-life character. My discovery of Biz was a little off in chronology, in the sense that when Biz was putting out those records on Cold Chillin’ in the ‘80s, I was just too young to know about them. I mentioned Pete Rock & CL Smooth’s album The Main Ingredient. That’s an album that I really studied. Pete Rock’s scratching was a big source of inspiration for me. On every song, there was some sort of scratch solo. I would try to figure out how he was scratching, but also what he was scratching. And for some reason, Pete Rock was scratching Biz records on more than half of the songs on that album.

So that album, which was one of the first albums that I really studied, gave me an amplified, exaggerated importance to Biz. That album may give me the impression that everyone scratches Biz vocals all the time, and if you’re just getting into scratching, you have to have Biz records. That isn’t wrong, but maybe it was a little exaggerated. So I would go to the record shop in Montreal, and I would ask them for Biz Markie records. These are records from a whole other period, so he didn’t have them in stock. He was trying to order this compilation for me, because I was pestering him every week, going to the shop and being like, “do you have Biz Markie records?” And the guy was like, “dude, I ordered them.”

So, I was just waiting for this order to come in, and what he was able to eventually stock was that compilation. It came in and I proudly brought it home. I finally had the Biz Markie greatest hits! And I just fell in love with all these songs, like “Pickin’ Boogers” was just so funny, but at the same time, actually dope. And I was discovering Marley Marl beats for the first time, anachronistically in 1994 or so. I’m sitting here listening to “Nobody Beats the Biz” just being like, damn, that’s a great beat, which is true, but it was also a whole different world.

One of your selections was Peanut Butter Wolf’s My Vinyl Weighs A Ton. Can you talk a little bit about that?

I mean, I’m on the album and, yeah, it was amazing to witness. Wolf played a big role in the early years of my DJ career. But I would even say he’s someone who helped open my mind. Because, in a sense, turntablism was a whole universe unto itself in those years. If you were a scratch DJ in that branch of turntablism, you could almost not be aware of everything else about being a DJ, and a record digger, and a hip-hop producer. And that was the case for me because I had started my DJ career in that branch of turntablism. I began as a super-specialized battle DJ.

It was only when I met a couple of other characters who took me in almost like their little brother and showed me all these other things that come with collecting records and being a DJ, that I realized that there was more to the world than just scratching on “Aah” and “Fresh.”

A little bit before making My Vinyl Weighs A Ton, Peanut Butter Wolf was featured on a compilation called Deep Concentration that my friend Joseph Patel put together. There was a tour organized to promote Deep Concentration and PBW and Cut Chemist were the resident DJs of that tour. Joseph inquired about getting two local DJs on the Montreal show, me and Kid Koala. I was maybe 16, but I had won the DMC championship, so people in the scene had heard about me. These guys had to call my house and ask my parents’ permission for me to come and perform at the Montreal stop of this tour! So that’s how I met Peanut Butter Wolf and Cut Chemist.

Wolf and I struck up an odd-couple kind of friendship because I think we’re about 10 years apart, and I think we both have a strange sense of humor. And I think he also must have looked at me as just some weird scratch kid who was taking an interest in it. He thought it was cool that there was this sort of little wunderkind.

You were a child prodigy. I think that’s how people saw it at the time. We all wondered, “how is he so good at this so quickly?”

In hindsight, I see how strange that was. And so Wolf kept in touch with me and we stayed friends. If I was going to be in San Francisco or LA, wherever he was living at the time, I would often end up staying with him. Those trips were super educational for me because he would show me all kinds of things, whether it was where samples came from, weird drum machines, or just the lore around record digging.

I saw him build up Stone’s Throw in those years. I was able to witness when he signed Madlib. Once or twice a year, I would go stay with him and just get the download on all this wonderful stuff that he was finding. And when he made his album, not only do I remember hearing a bunch of those tracks as they were coming together, but he asked both myself and Kid Koala to feature on the mega scratch posse cut “Tale of Five Cities.”

I’d like to talk about Non Phixion, The Future Is Now. What’s your relationship with that record?

That’s a very personal story, too. As my brother and I made our way into the independent, backpack hip-hop scene of the late ‘90s, we shared the basement at our parent’s house as a kind of studio. My brother was improving at making hip-hop beats, and I was doing my scratch thing, and I was winning these battles, but back at home, it was still just me and him perfecting our craft together.

We started our first independent label called Audio Research, and we were able to get distribution with Fat Beats, which was pretty crazy for us, being in Montreal and getting the mecca of American underground hip-hop to take us on. They were featured on one of these Canadian 12-inches that we made. We had a group called Obscure Disorder that was really just Dave, me, and our friends from high school rapping on them.

We would go down to New York a couple times a year. Each time we would meet some heads from the hip-hop scene, especially at the Fat Beats store. We met Ill Bill there, he worked at Fat Beats and he had heard the records that Dave and I were putting out. He liked Dave’s beats, he was aware of my DJing, and we forged a friendship with his group, Non Phixion.

“Bill asked my brother for some beats, and he picked one beat and recorded this crazy song called ‘Cult Leader’, and asked me to do the scratches on it.”

At the time, Non Phixion were working on their opus of an album The Future Is Now, and they were getting beats from Premier, Large Professor, Pete Rock, and, of course, Necro. This was the first album since Illmatic that had Premier, Large Professor, and Pete Rock on the same album. Bill asked my brother for some beats, he picked one and recorded this crazy song called “Cult Leader”, and asked me to do the scratches on it. So, for Dave and me, being on that album was a huge honor, because it was recognition from the real New Yorkers.

We still saw ourselves as humble Canadians just trying to do it right, to try to be respectful to hip-hop and find our way into the scene. These behemoths of the indie scene in New York invited us onto this awesome album, and it’s still something that we’re super proud to have been a part of.

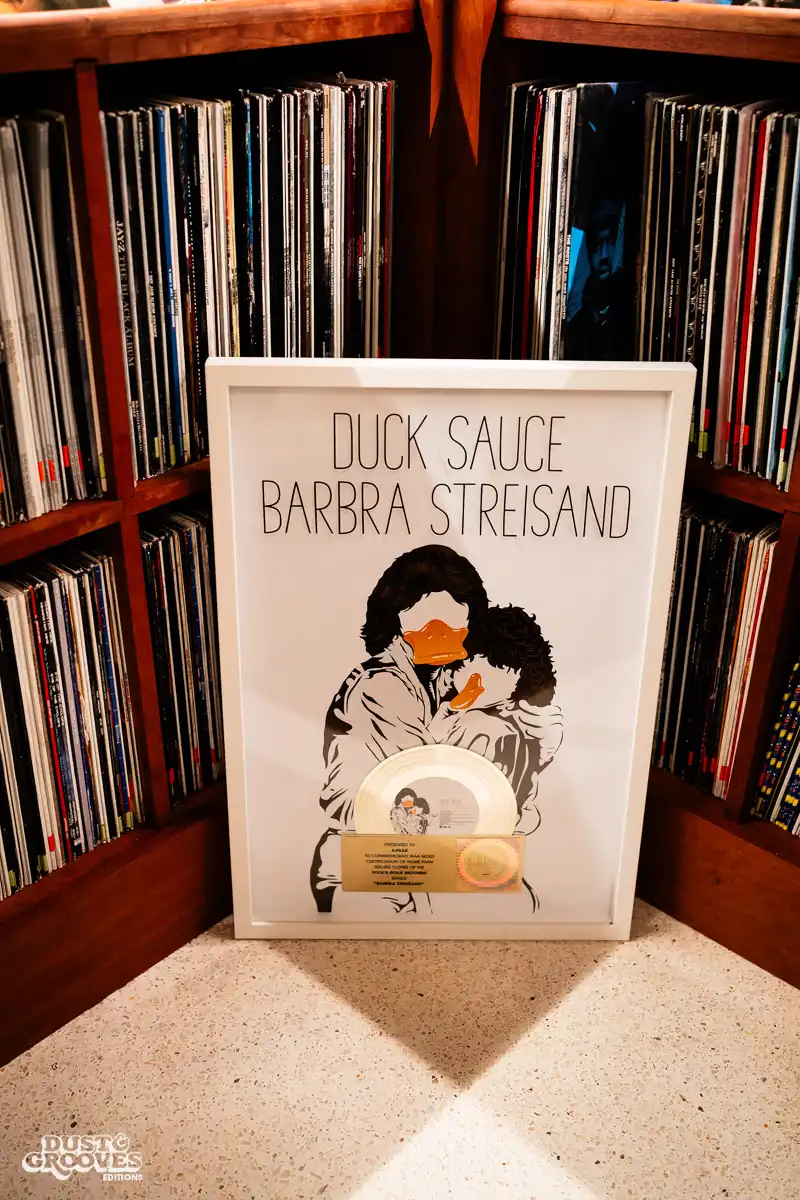

That’s phenomenal. We noticed a copy of the gold record for the Duck Sauce song “Barbara Streisand” at your place. How does it feel to have a gold record? Do you care about stuff like that?

Yeah, for sure, I care about having a gold record, especially with that one having been a record that was made with no intention of trying to make a hit, right? That’s the sweetest kind of victory where you’re not trying to reverse-engineer something to sound like other hits. It was just Armand and I being goofballs in the studio and just trying to find these little moments of earworm, but also just cracking each other up.

And that’s how the song “Barbra Streisand” came together, and it’s an absurd record. It’s illogical for it to have been a gold, and even in some countries, a platinum record, literally the number one song in a bunch of countries with no kind of chorus or verse structure. It’s just a loop that, I guess, is catchy enough, an inside joke that is too absurd to even explain, but that somehow tickled people, and you end up with a plaque. It makes no sense, and I’m proud of how it makes no sense.

“We had no intention of making a hit. That's the sweetest kind of victory. It was just Armand and I being goofballs in the studio trying to find these little earworms, but also just cracking each other up.”

A-Trak Tweet

A-Trak is a turntablist, DJ, producer, and president of Fool’s Gold.

Further Adventures in Record Collecting

Dust & Grooves Vol. 2

A-Trak and 150 other collectors are featured in the book Dust & Grooves Vol 2: Further Adventures in Record Collecting.

Become a member or make a donation

Support Dust & Grooves

Dear Dust & Groovers,

For over a decade, we’ve been dedicated to bringing you the stories, collections, and passion of vinyl record collectors from around the world. We’ve built a community that celebrates the art of record collecting and the love of music. We rely on the support of our readers and fellow music lovers like YOU!

If you enjoy our content and believe in our mission, please consider becoming a paid member or make a one time donation. Your support helps us continue to share these stories and preserve the culture we all cherish.

Thank you for being part of this incredible journey.

Groove on,

Eilon Paz and the Dust & Grooves team