For crate diggers and record collectors of the early 21st century, no magazine was more important and influential than Wax Poetics. Dedicated to covering a wide swath of groove-oriented music that touched upon everything from contemporary hip-hop, jazz and funk to old-school Latin, soul and disco, the magazine connected the dots between past and present with one deep dive after another into records both massively influential and impossibly obscure, as well as the folks who made them and the artists who were impacted by them.

“Like I always used to say: It’s not your father’s magazine,” says Andre Torres, who co-founded Wax Poetics in 2001 and served as its Editor-in-Chief (as well as overseeing its associated book and record imprints) until 2016. “It was, in a sense, because he would probably know a lot of these artists that we covered, but the way that we were framing everything was definitely from the record-digger, sample-hunter kind of perspective.”

The magazine’s very existence was a by-product of Torres’ own adventures in crate digging, and each Wax Poetics issue was deeply informed by his insatiable hunger for new discoveries of the dusty variety. Though he’s since transitioned out of the magazine publishing world and into the music industry—working for Universal Music Group and Spotify before most recently serving as Warner Music Group’s senior vice president of global catalog development and marketing—Torres still lights up like a little kid when asked about his favorite records and the circumstances that led him to them, and he graciously pulled out an impressive stack of wax for our photo shoot at his Los Angeles crib.

"I think my desire to create Wax Poetics was partially born out of this feeling that I had missed out on something."

Andre Torres Tweet

Andre, thanks for talking to us. Do you have a time limit for this interview?

Well, I’ve gotta go to physical therapy later. I have two herniated discs in my neck; they tell me it’s from many years of stress and not properly letting it out [laughs] Running Wax Poetics was pretty stressful at times, so I imagine that’s where most of it came from—but it was certainly well worth the journey.

Well, let’s talk about that journey. Tell us who you are and where you’re from.

My name is Andre Torres. I am currently residing in Los Angeles; I was originally born in New York, in the Bronx. But I grew up mostly in Florida and then moved to New York after college. I was there for about 20 years, before moving out here to LA about six years ago.

When were you born?

Born in 1969.

What’s your earliest musical memory?

Probably dancing to James Brown in my parents’ living room in the Bronx. You know, I have actually seen some Super 8 footage of me doing that, so it’s not just a memory. Evidently, I was the sort of family entertainment after everybody had a couple of cocktails; they would throw on some JB and I would do a little dance on the floor.

My father actually owned a record store in the Bronx called The Stump. That, I do not remember. I remember there being a lot of records around when I was younger in New York, though, and clearly that’s why; but when we moved out of the Bronx to Florida when I was three, he left everything. He started kind of getting back into buying records, mostly at thrift stores, when I was in high school. I’d become a hip-hop fan by then, and as I’m coming back from college, I’m like looking at his records and realizing, “Oh, wait—this is Les McCann’s Layers, I’ve heard drum samples from on here!” And he’s like, “Yeah, I’m rebuying all these records that I had.” And then I’m realizing “Wait, you had all these records in the Bronx? Like, you left them?” I felt like I’d been robbed of, you know, my inheritance. [laughs]

So I think my desire to create Wax Poetics was partially born out of this feeling that I had missed out on something, knowing I had kind of been ripped out of the Bronx. We left the Bronx in 1972; my father tells me stories about guys coming into the record store and wanting to write their name on the wall—they had like a number after it, so it’s clearly the beginning of graffiti. He and I were recently trying to figure out where we lived in the Bronx, and he’s walking me around the old neighborhood on Google Maps and showing me where everything was. “See this Chinese place? That’s where the record store was.” And the space is split with a laundromat, but back then it was a pet store, and he opened up a record store on the other side of it. He was like, “I had some of the Black Spades—” I’m like, “Wait, the gang?” And he’s like, “Yeah! They were always running around the neighborhood! There was some construction on the street, and they grabbed this big stump that had been pulled up. I told them, ‘Bring that stump over here! Put it in the window.’” That’s why they named the record store The Stump. My grandmother was evidently selling gold chains out of the trunk of her car, and he told her, “Bring some of those chains over.” He hung the chains on the stump and then they started selling jewelry out of this store. So it was basically a pet store/record store/jewelry store in the Bronx in like, 1970, ’71…

And then I put 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, the birthplace of hip-hop, in Google Maps, and realized it was literally like a five-minute walk through the projects from our home. I was like, “Wait, you moved us out like literally a year before everything started happening!” But growing up in the Bronx in the 1970s would have clearly been a different type of childhood than I experienced, so…

"The vibraphone is my favorite instrument; it’s always had a sweet spot in my heart, I heard a lot of this music growing up. This is literally where I started, and where I’m coming back to. Even with all the insanity that I deal with in this industry, it reminds me exactly why I’m still committed to this shit.”

Andre Torres Tweet

Can I ask why your dad moved y’all from the Bronx down to Florida? From what you’re saying, it sounds like a pretty sudden thing, like he had to get the fuck out of there…

Very much. I guess he would be comfortable with me telling you—though I keep telling him he should write a book. He was not a drug dealer, per se, but a “connector” of sorts, as he calls himself. And the RICO laws had just gone into effect, and there had been some federal agents coming by the house, asking around where my father was, and he thought, “I think we need to go.” So yeah, that was part of the reason why we just got up and left in 1972 and moved down to Tampa, which is where I grew up.

And that’s why he didn’t take any of those records with him.

Yeah, exactly. There wasn’t a lot of planning in that move, I don’t think. As I’ve gotten older, he’s revealed more of this story, which I clearly had no idea of when I was younger.

So you came of record-buying age when you were living in Florida?

Yeah, pretty much. I think college was really when I started getting deep into it, going around to like, every thrift store in Gainesville, where I was attending University of Florida. At that point, I was getting records for ten cents. Now when I go into Goodwill, they want four dollars for a record; I’m like, “Wait, you know that this is Goodwill, right? Four dollars?” I mean, there are dollar bins at actual record stores with cheaper records!

"Fruko was such a character; the bizarre nature of some of these sort of synth sounds that he was coming up with, we were like, ‘Yo, who is this dude?’”

Andre Torres Tweet

Yeah, I was in my local Salvation Army just today, and they had a sign saying, “All Records $2.99!” I was like, “Come on!”

Thank you! [laughs] Oh man, inflation—it’s really done a fucking job on us here. So yeah, I was buying stacks of records at ten cents apiece, just based on the cover, and just looking for samples. I found all these amazing disco records that I was like, giving away to people, and later on I started realizing, “Oh wait, this was the beginning of all the hip-hop breaks!” And I was going back home for the holidays, digging through my father’s collection and just stealing stuff right off the top.

I hadn’t quite pieced it all together at the time, but my grandfather was born in Puerto Rico and had moved to New York, and he was there for the Spanish Harlem heyday; he tells me stories about running around town with Tito Puente and all of the Latin jazzists. So that was very much a part of my childhood growing up—like, having big dinners at my grandmother’s house with pork and lots of rum and dancing, but always Latin music playing and lots of Latin jazz. And so I’m back from school digging in my grandfather’s records and pulling Lou Donaldson and all kinds of things like that out.

So you weren’t buying records before college?

Well, I think the Columbia House Record Club was where I started first buying records when I was a kid. I was obsessed with Kiss, so I had like, every Kiss record: Alive!, Destroyer, I had all of them. In our 4th grade class photo at Corpus Christi Catholic School, my friends and I decided we were all going to stick our tongues out like Gene Simmons. Then we took the photo and I stuck my tongue out, and then after I’m like, “Did you guys do it?” They’re like, “Oh, no, I got scared.” And I’m like, “Wait, what?” And of course, the photo comes out, and I’m the only one like, “Eeeh!” I had to apologize in front of the class and my teacher was all mad like, “You ruined the class photo!” [laughs]

"I remember this Kawaida record was kind of beat, but I just flipped it over and saw Mtume, Tootie Heath, Buster Williams, Don Cherry, Herbie Hancock, Jimmy Heath, and Eddie Blackwell, and I'm like, ‘It's a done deal!'"

Andre Torres Tweet

How did you go from Kiss to hip-hop?

I think in Florida at the time, the big rock station was 98ROCK, and then there was a Black station called WTMP that I used to tape from all the time. I was getting into hip-hop through breakdancing, but I wasn’t able to buy a lot of records. There was a DJ on WMNF who totally got it, Kenny K; he had the first hip-hop show in Tampa, and I used to tape the hell out of that. He actually was part of the crew that Shock G came out of; Shock G is definitely an Oakland guy, but there was some time that he spent in Tampa, and Kenny K was part of that. And yeah, that was a big part of my musical upbringing.

I was also big on going to the library as a kid, and I started getting into their cassettes. They would have all these weird jazz tapes and cassettes I would bring home, like Spyro Gyra and Pat Metheny. And hip-hop cassettes started making their way to us, so I was listening to, like, Slick Rick, Fat Boys and Run-DMC throughout high school; in 10th grade, I’d be doing my little breaking routine during halftime at the football game. I started to get into R&B stuff like Janet Jackson and Sade, because my father would be listening to the radio and be like, “Oh, this is a jam here.” He started getting me into more of that sort of smoother shit.

There was also a lot of reggae, pre-college; one of my first jobs, I was bagging groceries at Publix, and there was an older dude who did stock who lived across the street. He was already in college, and he would make me these reggae tapes. I eventually ended up going over to his crib, and it was like, “Yo, what the fuck?” There were records all over his crib, and he had these fucking big-ass reggae sound system speakers and shit. Now, I knew about, like, Bob Marley, but this dude cracked it open, introducing me to U-Roy and Eek-A-Mouse and Yellowman and the early version of Dancehall. He would make me these tapes that then I would take to school, and the homies were like, “Oh, let me get a dub of that!” And living in Florida, we would leave school and go get beer and go to the beach, so that was the soundtrack to high school. It was, like, going out on somebody’s boat with a 12-pack of Natural Light and listening to U-Roy all afternoon and smoking weed.

That all sounds pretty awesome.

Yes, I actually think back fondly now, like I should try to do that again at some point soon. But yeah, that was definitely a large part of my upbringing. Always lots of music, but it wasn’t until college that I really started collecting vinyl. I got suspended during my freshman year in college for selling ecstasy, and they told me I had to take a semester off. Now, that was transformative, because that was back around the same time as Paul’s Boutique, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, Ice-T’s 6 ‘n the Mornin,’ De La Soul 3 Feet High and Rising. I distinctly remember riding around listening to all these records, and they cracked my world open. So, that really became, like, the new obsession. Once I came back to school—I was going to art school—I was just obsessed with hip-hop, and then eventually became obsessed with finding the records that had all these samples on them, which set me into a whole ‘nother course.

"I was just obsessed with hip-hop, and then eventually became obsessed with finding the records that had all these samples on them, which set me into a whole ‘nother course."

Andre Torres Tweet

Were you DJing? Or were you just digging because you wanted to hear the source material for all these hip-hop records?

I mean, I knew people who would have house parties, and I might bring some records. Once I moved to New York, it was the early days of Williamsburg and there might be a hundred people in a warehouse space that my homie worked and lived in, and I’d put on some Serge Gainsbourg, and all the fuckin’ hipsters would go crazy and shit. But I never thought of myself as a DJ. I always knew guys who had so much more knowledge than me, and who had a better understanding about how to manipulate that equipment in a meaningful way. I loved the music and loved the records, but I never really considered myself good enough that I would ever call myself a DJ. But yeah, I love being there in the booth with the guy, looking over his shoulder and going, “What is that? Oh, shit! I gotta get this!”

You know, I think a lot of the idea for Wax Poetics came out of that, where I was obsessed with collecting all this information. This was in the beginning of the internet, and there’s these chat rooms and places like thebreaks.com, and I’m trying to go into record stores with these lists and all this stuff. I’m like, “I got to consolidate this information in some way—there’s got to be a better way!” And that was kind of where the magazine came from.

I’ve read that the magazine also kind of came out of a documentary you were trying to do on crate diggers. Can you talk about that?

Yeah. So by now, I’ve left Florida and moved to New York to get my master’s degree in painting. I was buying a lot of records; I didn’t have much money, but I was digging a lot in New York, and now I’m starting to understand, “Oh, there’s like real culture here.” I’m in the middle of where all this started. I was kind of floundering around, trying to make a living, so I cut my dreads off and turned into Corporate Andre—and the next thing you know, I’m a temp, and this guy kind of takes me under his wing. He winds up leaving the company I was temping at and says, “Hey you should come with me to this IT company; you can be a recruiter, and I think you’d be good at it.”

So now it’s like 1998, and I’m wearing a suit and tie every day and I’m working in the World Trade Center. I’m making pretty decent money, and now I’m ordering records obsessively, and getting them delivered to the office because I don’t want them coming to my crib in Brooklyn. This was the really early days of eBay, and I was finding all these great records for not a lot of money—things that I’ve since had to get rid of when I went broke. My homie Brian DiGenti, who became my partner and editor, moved to New York as well, and we would go looking for records. And then at one point, he moved out to San Diego, so we would kind of communicate back and forth and just play each other’s records and stuff. I would be asking questions on the chat boards, intellectual stuff about Black music and this period or that and these musicians and how music changed, and he would be like, “Bro, you can’t ask those kinds of questions on these chat boards—they just want to know where the breaks are.” I’m like, “Yeah, but there’s all this history and music and all that…”

I’m seeing that there’s guys in Italy, in the UK, all over, that are collecting records. I’m like, ‘Somebody’s got to do something with this community.’ I had a friend who was a filmmaker, and I just thought, “Maybe we could do a documentary.” So, I’m going to all these bookstores, Barnes & Noble and Borders, to do research. I’m going in looking for stuff about people like David Axelrod, and there’s nothing. Even the regulars, the usual suspects that we know now, like the James Browns and the Sly Stones… just nothing. There were multiple Beatles books and Rolling Stones books, but I was like, ‘Man, literally nobody has documented this shit?’

And so, that was the kind of lightbulb moment. Wax Poetics was born out of that personal desire for somebody to document a lot of this stuff, as well as stories from people who have been collecting records for a long time. And, you know, trying to kind of somehow coalesce all that information into one useful handbook where you could be like, “I’m gonna take this thing and build a record store.” At first, it was kind of just me selfishly putting something together for myself, but then I realized, “I can’t be the only one who is interested in finding out more stories about some of these guys.”

"And so, that was the kind of lightbulb moment. Wax Poetics was born out of that personal desire for somebody to document a lot of this stuff, as well as stories from people who have been collecting records for a long time."

Andre Torres Tweet

All that eventually kind of came to fruition when I realized, “Fuck, I guess it’s got to be us!” I was a big fan of hip-hop magazines, and I’d gone to art school, so I used to get a lot of art journals. And I had met Brian when I was writing music reviews for this magazine Jazziz while I was in college; we both had a common friend there who was an editor. So we kind of just started talking about this idea of like, “We should do a magazine about all these ‘breaks’ records and all the stories we hear. We could talk about, like, Madlib and them, but then we could interview all the old dudes.” I had no idea about magazines or distribution or content creation or any of this; it was really just like, “Yeah, I want to read some stories about these dudes.”

I was buying up all these hip-hop magazines, and they might have one article on a record collector or a break or a sample. And I remember, I just ripped out all these record-nerd kind of articles out of like, Vibe and Ego Trip, and pieced and stapled them all together; I said, “Here’s literally what the magazine would be: Just all record-nerd shit, but through the hip-hop kind of lens.” So yeah, that was pretty much how it all started. Again, not having any idea what the fuck I was doing—or any of us for that matter.

Practically every issue of Wax Poetics turned me on to artists and music that I’d never heard of—or at least had never really explored. Did you have the same experience while working on the magazine?

Yeah, yeah. We were kind of all stumbling our way through it together, but over time, you start to realize, “Oh shit, this is turning into something!” So yeah, it was very educational. Somebody might tell us, “Yo, Jabo Starks lives in my neighborhood,” or, “I saw this guy playing at this bar, and I started talking to him. You guys want to interview him?” And I still love the fact that some of this stuff, some of these articles, was almost like a race against time at some point. There were times when someone we interviewed would pass away before we even got a chance for them to see the article.

"I'm going to all these bookstores to do research. I'm going in looking for stuff about people like David Axelrod, and there’s nothing. Even the regulars, the usual suspects that we know now, like the James Browns and the Sly Stones… just nothing... I was like, 'Man, literally nobody has documented this shit?'"

Andre Torres Tweet

“I’m realizing in my life now, like, everything’s so mass produced and nothing’s timeless like it was, and I feel like I’m reflecting on the history of music, and it’s like, vinyl really helped people, vinyl and physical formats really helped music become timeless."

Caroline Cardenas Tweet

How did the experience of publishing Wax Poetics affect your own record collecting?

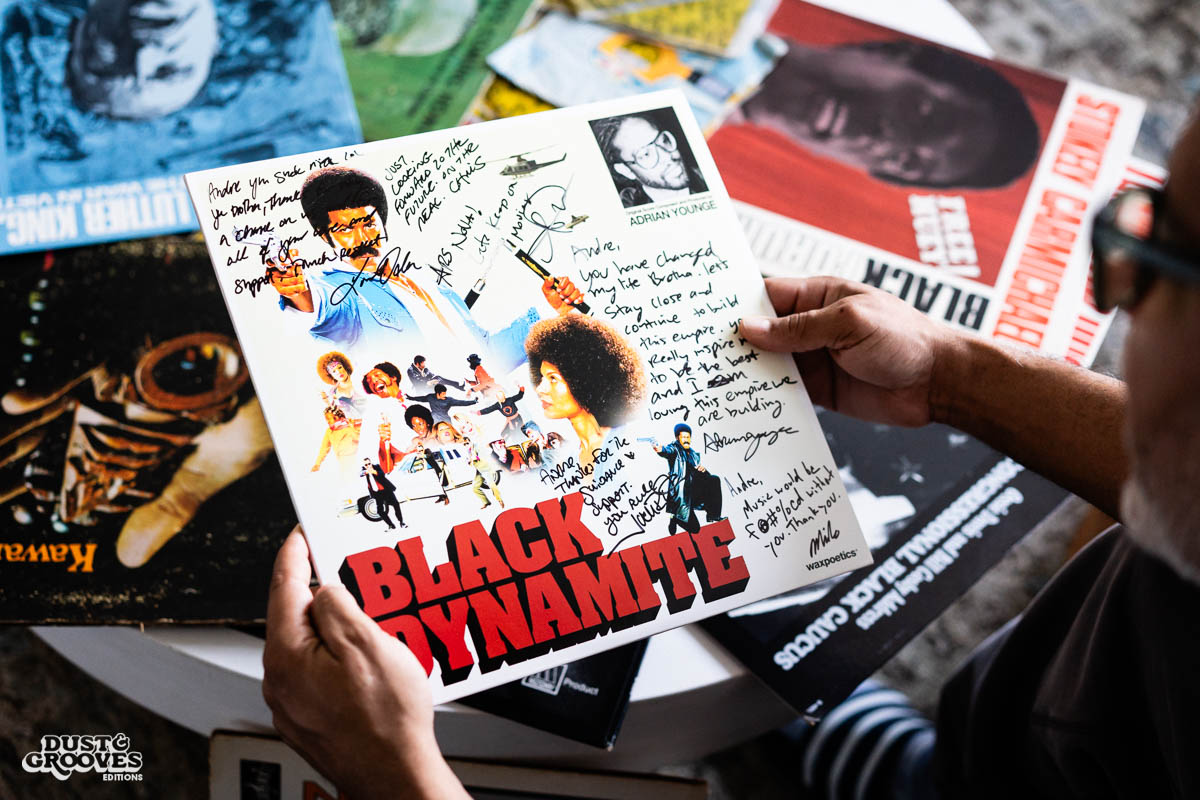

Oh my god—it became, again, a race against time. As I’m reading an article that’s going to be in the next issue, I’m on eBay looking to see if these records are accessible and available at a reasonable price point; because I know if I publish this article, this record is going to increase in value tenfold. I would see it happen with certain records; people would tell me, “Oh man, that record you guys did that article on in Wax Poetics—it’s going for $100 now.” I’m like, “Wait, what? Damn! I should have bought it.”

I started to actually try to get ahead of the curve a little and use some of that advanced intel. I’m like, “Huh, this one’s only $10 bucks on eBay? Why don’t we put a bid in on it now!” [laughs] But it was an educational thing for me, too. A lot of this stuff I wasn’t aware of until I sat down to read the article, and they were assembling all these record scans for the layout and I’m looking at the images going, ”Oh, shit!” I was reading and editing and purchasing and shopping at the same time.

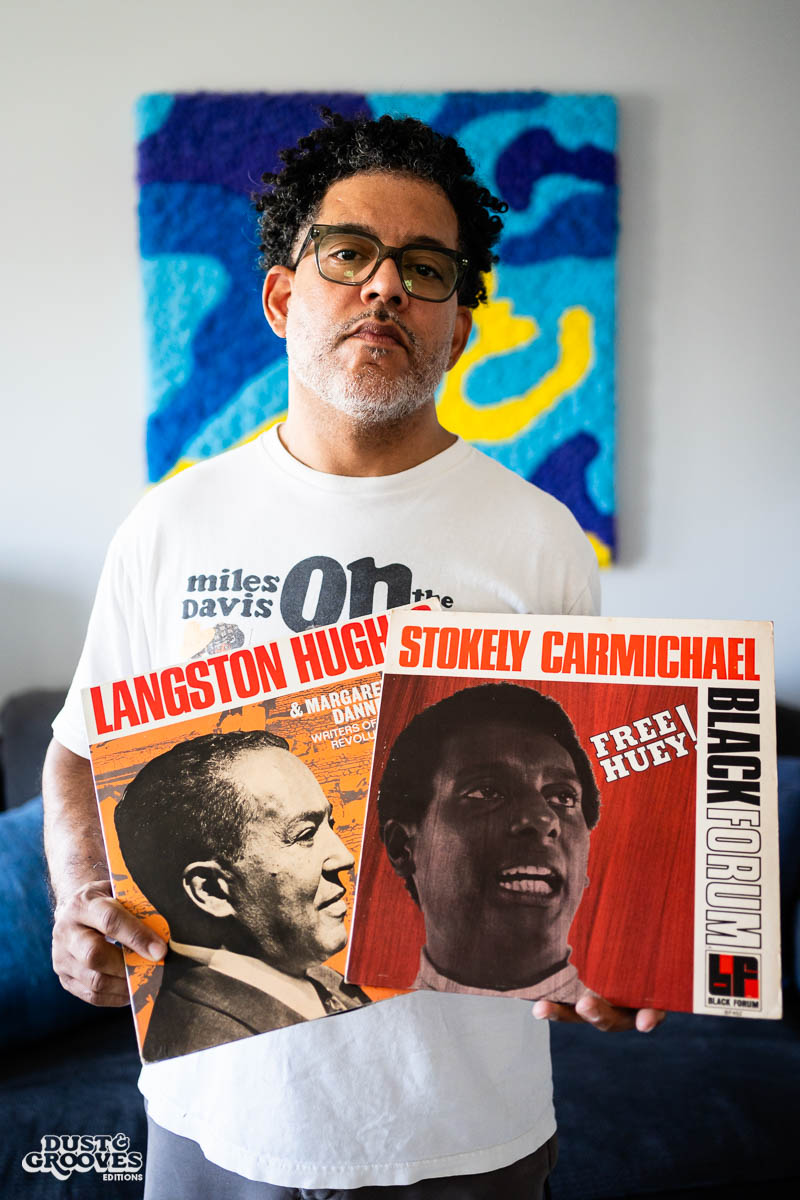

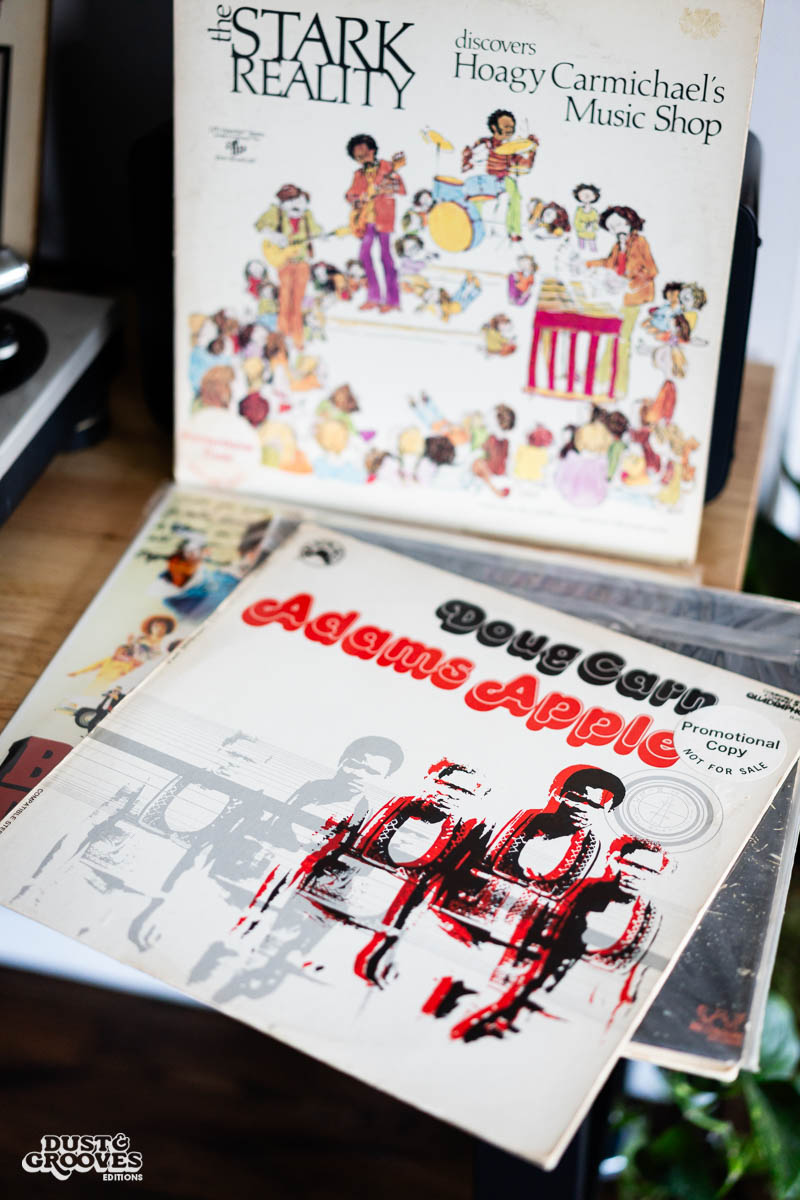

But it certainly broadened my horizons; now I’m looking for anything and everything. It completely opened up my world to Brazilian music and African music and Colombian music and Turkish shit, Persian, and I’m like, “Wait, this doesn’t stop!” I’ve got Andy Votel sending me records and I’m just like, “What is this Welsh rock thing you just sent me?” At one point, I wound up getting a chance to go to Korea with Amir; he’s buying $300 Korean records over there while I’m digging in the dollar bins coming back with stuff that I’m still holding on to that’s like, “You’ll never be able to find this now.” So, you know, it’s been eye-opening, to say the least.

And then, to be in the industry, first at Universal and then at Warner, and I’m sending my guy emails like, “Hey, have you seen this thing in the vault? Do we have the tapes for this? Can I even hear it? Is there a possibility we can reissue it?” Like, first it’s a personal thing, but then maybe there’s some commercial opportunity here—unreleased joints, things I’ve heard about but never heard, and I’ve actually had A&Rs in there who are able to go in and chase these things down. Sometimes I’ve gotta pinch myself and remind myself it’s all real.

You mentioned having to sell off records when you were broke. Fifteen years ago or so, dire financial straits forced me to liquidate most of my collection, and I stopped buying records for several years after that. I felt like I’d purged myself of “the sickness,” only for it to come back hard once I got back on my feet. Have you had the same experience?

Yeah, I’ve realized as much—the sickness may have subsided, but it never really goes away. For Father’s Day this year, my wife and oldest son bought me a tufting gun to make rugs with, but I’ve got to get all these records out of my garage so I can have the space to begin making rugs. I’ve got a call out to Amoeba to come and look at these records, but once they’re gone it’ll all just continue; I’ll keep collecting and trying to make shit, and getting rid of some records and getting some new ones.

Has what you’re looking for evolved, as well? For instance, I used to be all about buying obscure garage, psych, and funk compilations on vinyl, but now I really gravitate towards records where I can listen all the way through and not be bugged by tracks that seem out of place or vary wildly in quality.

Right there with you, man. I think it’s certainly an evolution, and I think the journey never quite ends until it’s all over. I’ve just kind of resigned myself to that fact, at this point. And I’m just going to enjoy the ride and not stress myself over it. I’ve been good about trying to keep it within certain confines, because you know how it gets to the point where it’s spilling over and it’s like, “Okay, I gotta have the guy come over here. I got too much. Come over and get some of this!”

Even with books—I still had a bunch of music books in my garage from my Wax Poetics days, and I went through them and took them into the office at work. I was like a drug dealer: “Hey, come over here, I got something you might be interested in!” (laughs) And all these people were coming in and going through them, like, “Oh, that’s my shit!” So over the course of a week, I was able to give them all new homes. That philanthropic aspect is also kind of rewarding; I started to understand how it must be for rich people to give away tens of millions of dollars at the end of the year—it’s a tax write-off, but hey, it feels good!

“Damn, these kids. They don't even understand the struggles we went through back in the old days!”

Andre Torres Tweet

Are you passing your records—and your love of them—on to your kids?

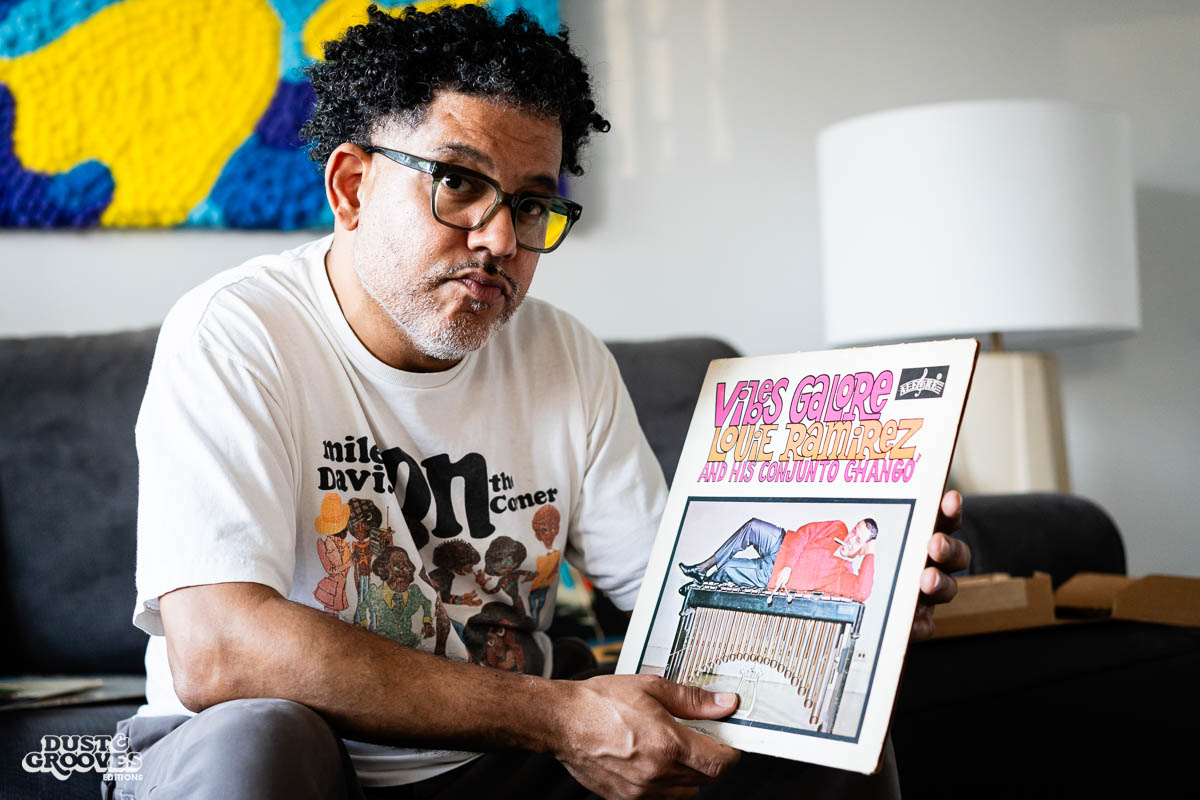

Yeah, you know, one of the prized records that I pulled out of the collection for Eilon to shoot is this Louie Ramirez album—the music is one thing, but knowing it was my grandfather’s adds a whole ‘nother level of meaning to it, especially now that I’ve had my own kids and I’ve started to share music with them and give them records. One of my kids is now buying records and collecting; for Christmas a few years ago, he asked for his first record, and I’m like, “Wow, amazing! This is dope. I love it.” So he sends me the link to it, and it’s like $100. I was like, “What the fuck? For your first record?” Like, there’s no ramping up here. I started out buying 10-cent records, and he just went right to the top. I was like, “Damn, these kids. They don’t even understand the struggles we went through back in the old days!” [laughs]

Andre Torres is the founder of Wax Poetics Magazine and a glue gun pom-pom master. He does not take pom-pom art commissions.

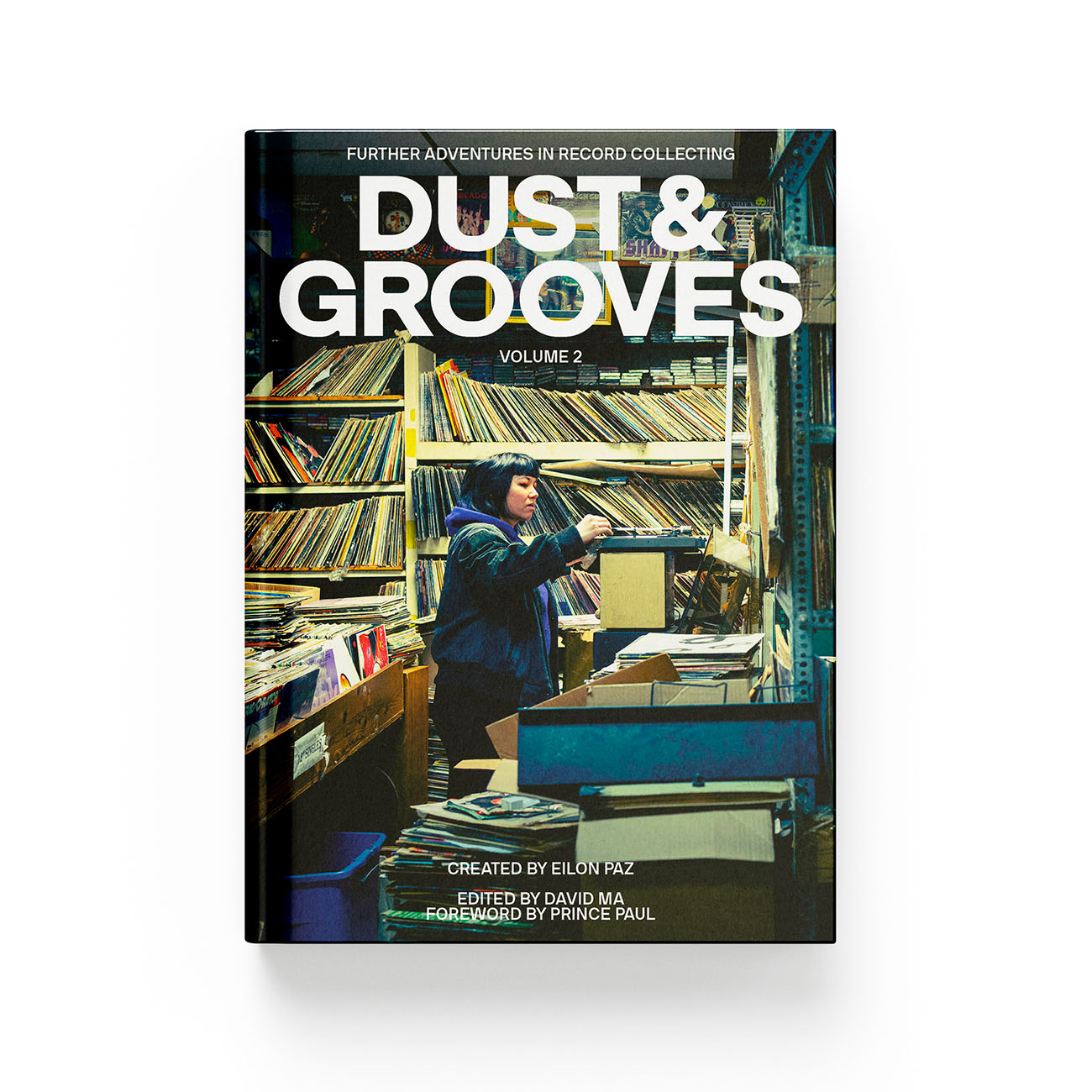

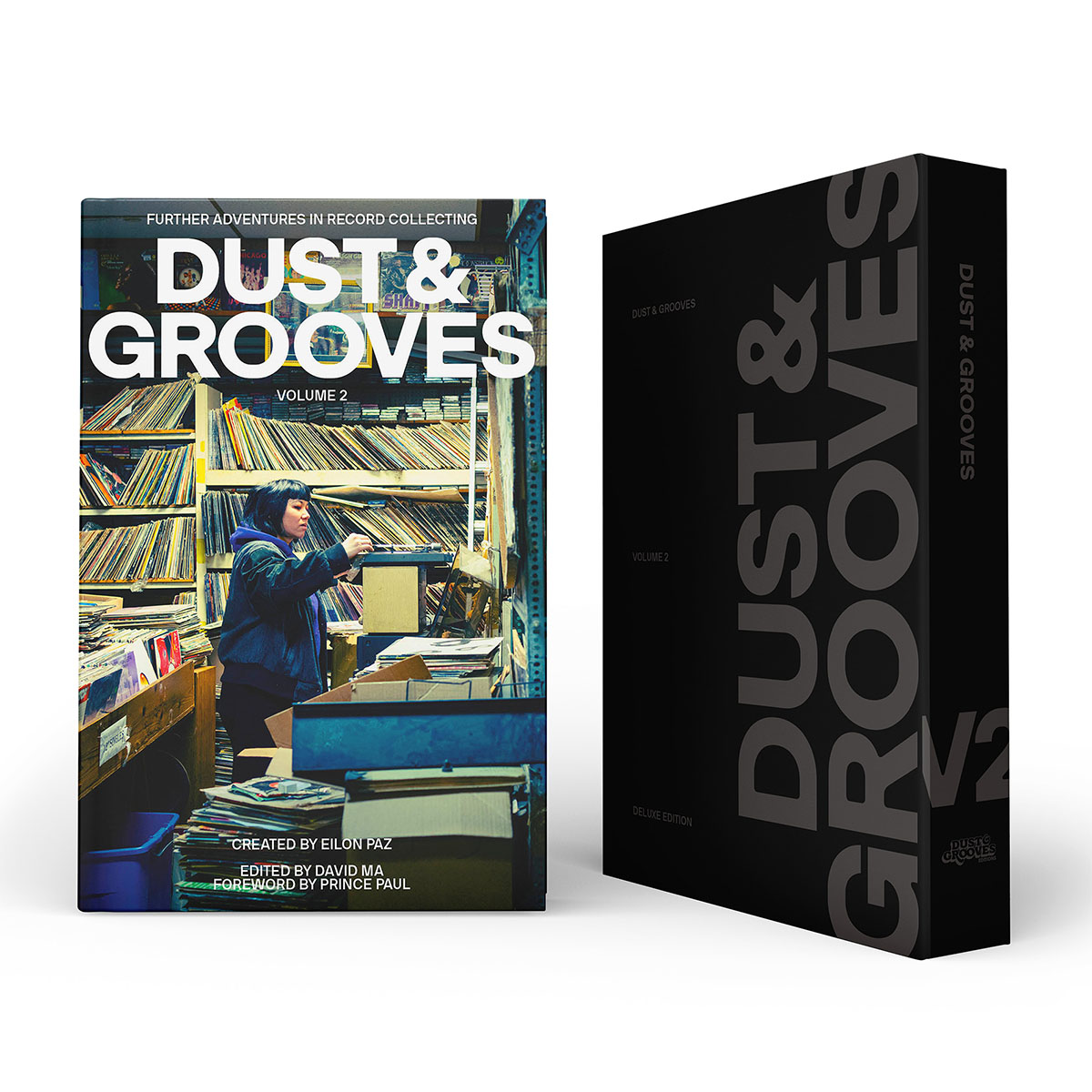

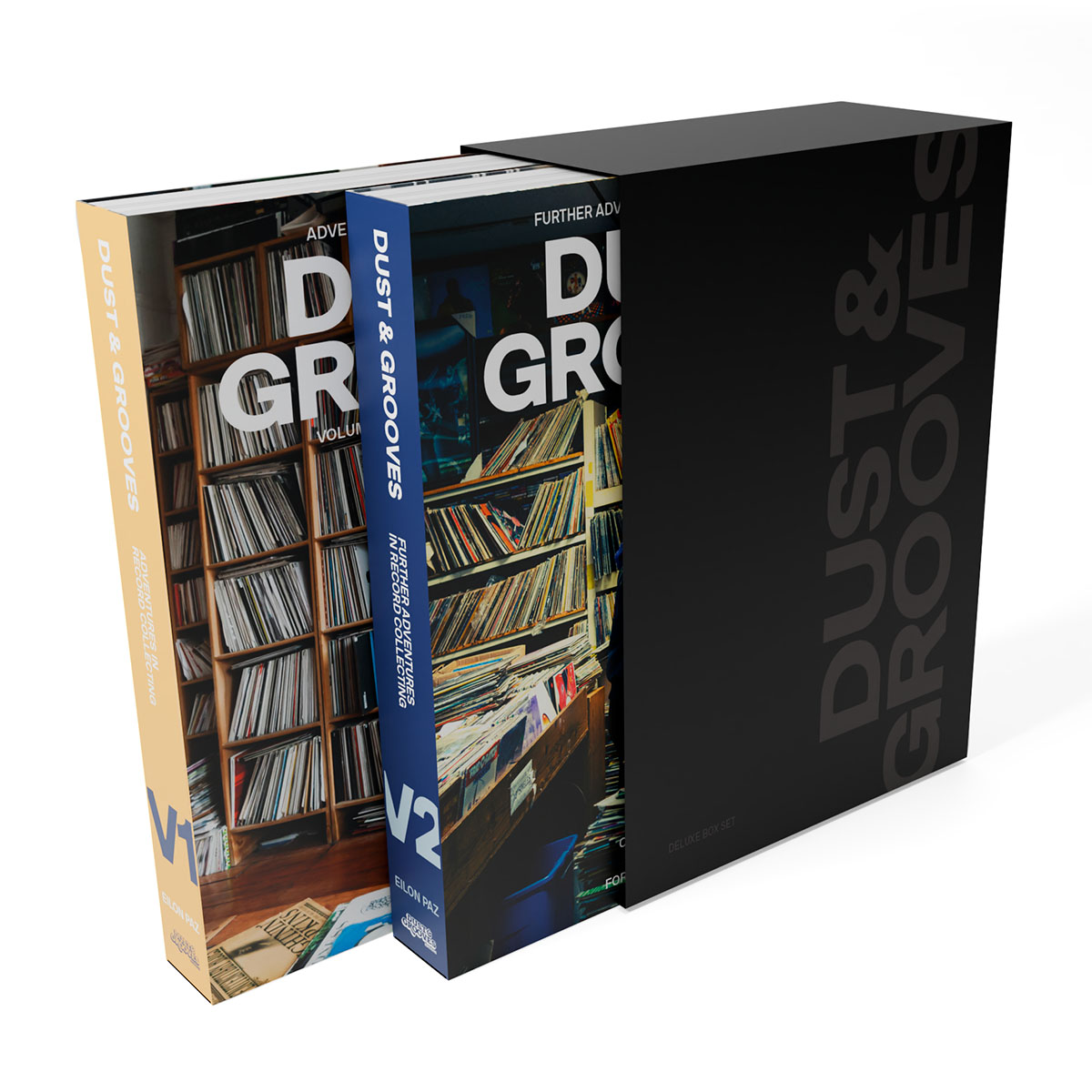

Further Adventures in Record Collecting

Dust & Grooves Vol. 2

Andre and 150 other collectors are featured in the book Dust & Grooves Vol 2: Further Adventures in Record Collecting.

Book drops October 15, 2024

Pre-order now

Become a member or make a donation

Support Dust & Grooves

Dear Dust & Groovers,

For over a decade, we’ve been dedicated to bringing you the stories, collections, and passion of vinyl record collectors from around the world. We’ve built a community that celebrates the art of record collecting and the love of music. We rely on the support of our readers and fellow music lovers like YOU!

If you enjoy our content and believe in our mission, please consider becoming a paid member or make a one time donation. Your support helps us continue to share these stories and preserve the culture we all cherish.

Thank you for being part of this incredible journey.

Groove on,

Eilon Paz and the Dust & Grooves team