When most interviewees for Dust & Grooves are chosen, they come highly recommended via word of mouth from the ever-expanding vinyl community—a friend of a friend of a friend. Eduardo Gregori’s connection with us came through a stroke of luck and being in the right place at the right time, when Dust & Grooves founder and boss at large Eilon discovered him working the mail orders at Brooklyn’s Human Head Records. The two struck up a conversation about Brazilian jazz, and the two came out with a vague plan: “if you ever want to go digging in Brazil, I’ll show you around,” Eduardo promised.

And so it was forged, when Eilon conceptualized a journey through the South American country to take stock of the modern record scene there. Legend had it that the country had been picked clean by record aficionados looking for their own piece of Brazilian music history, so he needed someone with a deep knowledge of the best spots to dig. He knew just who to ask for guidance. Eduardo Gregori, a New York acquaintance, became Dudu, Dust & Grooves’ close friend and Brazilian music genius. Thus, an investigation was launched into the scene for Dust & Grooves Vol. 2, complete with endless digs, sketchy hotels, and forever friends. “Letdowns and Jackpots: Holy Grails in Brazil” will be coming soon, but for now, I met Dudu for an interview to learn his insights into Brazilian digging and his music history.

Clever, casual, and self aware about the constantly shifting record scene, Eduardo’s music path came from family road trips through Argentina and Canada, where he wistfully listened to Joni Mitchell and initially antagonized the sprawling sounds of Dark Side of the Moon. It wasn’t long before turning into a bonafide record enthusiast, thanks to his early copy of The Offspring and a budding love of playing the drums.

This love came to a peak when he decided to move to New York to study jazz performance, occasionally DJing in his free time and supplementing his income through a stint working for the aforementioned Human Head Records. It was a combination that furthered his music knowledge, “Because I went to school for jazz, and worked in a record store after graduating, that opened up my mind a lot to go deeper into soul music.”

From there, he moved back to Brazil, where he continues his obsessive record digging to make extra money and occasionally guides curious minds like Eilon through the best places in the country to dig.

O General and Dudu soak in a mural of the legendary Brazilian soul icon, Tim Maia, in Vila Madalena, São Paulo. Off we go!

Getting things started, could you tell me a bit about who you are and your background with music?

I graduated first in filmmaking, then in music performance focusing on jazz. I divide my time between performing as a drummer, teaching, and digging. I’ve performed as DJ when I was in New York, and some jazz gigs as a drummer both there and in Brazil, but together with all of these things, I think music curation is what I do.

Could you tell me a bit about why you think film and music play well with each other?

It’s almost like they are inseparable, right? I think even before recorded sound in movies, there was music. It’s almost like music expresses more than words in film, and sometimes more than the image itself. But the application of movies into music is more abstract…I like to think there is a noose into music, but storytelling in music is much more abstract, and you’ve got to take those elements that are so abstract so seriously. Sometimes it’s just a sound that has a higher pitch and you have to create all of this storytelling because of these two elements.

It’s very similar to jazz, that improvised nature and moving a story.

Yeah, exactly. I think in jazz it’s even easier to see that storytelling sense than in groove-based music. It’s more delicate in the groove sense, even more abstract.

Dudu, Eilon and General taking a breather from digging in a messy garage

Going back a bit to your origins, what was the earliest memory that you had with music?

I forgot the year, but it’s funny because when I was young, we lived in a part of São Paulo where me, my parents, and my brother could just get a car and go down to Argentina. It would take like a week, and then we would go to Patagonia for two months. Music was everything we had in those trips, so in my recollection that was it—the Patagonia trip and tapes my dad made of mainly Joni Mitchell. But when I talk to my parents about that, my parents are like, man, you’re mixing it up, the Joni Mitchell tapes were from a much earlier trip to Canada, like Banff National Park with the big lake. Because it was Canada, my dad was like, okay, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, that stuff. Then after some years I remember him putting Dark Side of the Moon on for us to hear. My first reaction was like, ‘Turn that shit off!’ Because it was just noises from the introduction of “Time.” I was like, ‘That’s not music!’ But a few years later, that got me going.

I love that. I also have an origin story with Dark Side of the Moon, I feel like that’s something that every music obsessed kid has to go through. What was the first record you bought yourself?

That answer is not as pretty as Joni Mitchell. It was the Offspring CD—Americana is the record. I have an older brother, and he had the CD, or I had the CD, and we kept fighting because we both wanted to listen at the same time. So I ended up just buying another one.

Good sharing tip. Going more into your modern music appreciation, do you have any music specialities? You mentioned being a music curator, what worlds do you curate within?

My forte of music knowledge—which is not that big compared to some people I’ve met—is mainly popular Brazilian music from the 1960s, 1970s, and a bit of 1980s. But because I went to school for jazz, and worked in a record store after graduating, that opened up my mind a lot to go deeper into soul music.

Tim Maia’s spirit has been guiding us throughout the entire trip. In Guaratinguetá, some signs are clearer than others

Can you expand a bit on the kinds of drumming and DJ gigs you had?

I performed as a DJ for about one year at Jupiter Disco, Ore Bar, and Human Head Radio. I’ve also performed with Eduardo Brecho group, Freddie and the Freeloaders, and other jazz gigs. My genres have mostly been Brazilian, funk, and jazz funk.

I’m really interested in the idea of Brazilian versus American digging cultures and how they might be different, and because you lived in New York, you have two worlds that you can put together for your knowledge base. Can you tell me about the differences between digging in America versus Brazil, and how living in America might have helped you dig in Brazil or vice versa?

For starters, the obvious is that Discogs is not as well known in Brazil. It’s getting known at a fast pace, but in the United States it’s something that has already changed the market. Not only Discogs, but the whole internet—Ebay then Discogs, then maybe some other platforms, but it changed a lot of the game and, of course because of the pandemic everybody felt a push in the market there. In Brazil the difference is mainly the delay in technology and the delay of the consequences technology brings in. That’s really interesting, because it’s very costly information for those that dig now, but the difference in technology is also what makes some records in Brazil more expensive. In the 1990s, records in the United States were almost up, they were no longer producing those. But in Brazil and some other countries, even Europe, records were still being produced a lot during those years, when CDs started booming in the United States. There are many titles with a lot more volume in Brazil from that time, or they didn’t even come out in the United States. A perfect example is Nevermind. Nevermind is an extremely expensive record for an original pressing…I think it’s around $600 in good shape, it’s crazy! In Brazil, it was so popular and we were still pressing a lot of records, so we pressed a lot of Nevermind. There were only two pressings at the time, but the volume was big. That was a big gap in the years before. Now, people know about the 1990s pressings from Brazil, so even those are already disappearing and the price is going up. There are so many people coming into the record scene that records that were always so cheap are unpredictable. I support my income with records so I can do what I love, and I make a lot of my living in those records that are 1990s titles. It’s music that I started to really appreciate, like I discovered for instance that I really like one record from Alice in Chains, which is something I never expected. But most of it is not stuff I love, which makes it a bit easier for me to move.

That’s a great insight. As a Nirvana fan—who’s not, I guess—it’s very interesting to hear about different pressings because that’s something I didn’t even consider.

I think I have like, 30 copies of Nevermind. I mean, I’m gonna sell them all, I’m not gonna keep one.

Uncertified chauffeur Dudu and his co-pilot, O General, looking ahead.

Well, I’ll keep an eye out! Thank you for giving me some insight into how you collect these records to sell. I know Eilon mentioned that during the Brazilian digging trip that was one of your biggest goals, to find those Brazilian pressings. Did you find any on the trip? How was it digging?

The thing is with these 1990s pressings is that they are not that common, but when we do a dig like that I’m almost sure I can find one or two. Maybe not for a price that I can make a lot, because it’s also music that is popular in Brazil, you know, people love that stuff here. So I’m also competing with people that want to own the records. But I did find some Soundgarden, and I remembered that their original press goes for a lot of money because—somebody told me this and I don’t know if it’s 100% accurate—it’s the only totally analog press from the tapes…It’s pricey in the United States, that pressing. It’s funny, Eilon was like, “Really? Soundgarden at that price?” I was like, ‘Yeah, man, I don’t know. Chris Cornell, I guess.’ But for me the main goal is always Brazilian rarities, preferably ones that I already own or something that’s really pricey that I don’t care much about. I’ve realized that that stuff goes first, the main problem with those crazy Brazilian titles is that even here, prices aren’t low. You can’t make a lot as a reseller, because they are also sought after here in Brazil…Even here people ask for prices and I’m like, ‘Man, I’ve seen this cheaper in New York.’

Victor found this crazy Marcos Valle Garra record. That was great! We avoided any conflict because he found it and it’s a record I already own, so I was like, great, I didn’t find it, because it would be harder for me to deal with. But I found a cool 7-inch that is very rare, Tony & Som Colorido. Tony is actually Tony Bizarro, a Brazilian singer composer that recorded a few other sought after records. He were friends because of Tim Maia, so it’s very influenced by him. It was great because the next day Victor found the Garra, so I felt like, okay, now we each found heavy stuff for the first time in the trip, now we are good, whatever happens.

I know that you started curating this essential collection of Brazilian music for Eilon, can you tell me what you found that you knew needed to be in his collection?

Of course there were great titles, but we were like, these titles at this value, you have to get it. It’s not a fancy or expensive record but we found Secos & Molhados, which translates to dry and wet and is what we would call grocery stores back in the day here in Brazil. It’s a group that lasted only a few years, the lead singer was Ney Matogrosso. He’s a singer and still alive and performing. It’s a classic record that we used to find every time we dug, so we could really choose the best copy, because it is a great record, that’s why it came out so much and that’s why we used to find it. That was a record we felt the price would raise with a little time. Wf we had any sense in our mind we would follow that instinct because it’s just good and they are going to sell out because everybody needs one—anybody into records anywhere in the world, in my opinion, needs one…and now we are seeing it go from 20, 30—and I’m not talking like an old man, like, five years ago, ten years ago—I swear to god, it was like three months ago! And now I see it going for almost $100. No matter the price, this is a great record, beautiful. Also one of Brazil’s most expensive records, Arthur Verocai from the same year, is so rare because they took it out of the stores and melted it down to make this record, Secos & Molhados.

O General with one of the greatest findings of this trip, Marcos Valle’s Garra. Angels are everywhere.

They melted it down? What’s the story here?

Secos & Molhados was a record that sold a lot. That and Arthur Verocai’s Self titled were released by the Continental label, but Arthur Verocai’s album did not sell well at all and was misunderstood at the time. So, Continental pulled copies that hadn’t sold yet and they melted them all down in order to produce more copies of Secos & Molhados.

The vinyl circle of life. Moving a little bit further into the trip, can you tell me about your relationship to Victor and how you decided who got what records?

Yeah, that is one of the hardest things about it. With any of my friends it’s difficult, it’s not the first time I’ve done it and it’s not the first time I’ve done it with Victor, but I think Victor is a good person to do it with. His family is Brazilian-German, his father is German, his mother is Brazilian, so he’s got a bit of both. He’s got the emotion, but also wants to be precise and fair. It’s his personality to write down all the costs of the trip and be right to every cent, which I really appreciate. That’s the way he connects and I wouldn’t have it any other way. From the beginning of the trip, I was like, we have to find a way to not turn this into what I would call a crazy race—let’s act in favor of both. We would separate the records into criteria: records we don’t want were not even considered, records we both wanted and didn’t own yet, records that both of us already owns and are good to make money off of, and then there are the records we find that one of us don’t own and wants it. That person calls dibs. At the time, Victor wasn’t thinking about reselling, that was more for me, so that made things a bit easier.

Eilon said that you two had some arguments during the trip. Was there any debate over who got what, or was this unrelated?

Of course, there is that, but I think it wasn’t related. It was more like an old couple, when you know each other that long and make a week long trip together, of course you’re going to fight over anything. Deciding who gets what was in the background of that, but we found other things to fight about. It was funny because it was the two of us in the front, and Eilon always in the back of the car. I do all the driving because Victor doesn’t want to drive, which is okay by me, since he is good at doing most of the research. I saw that we were getting into an argument at one point so I told Eilon, ‘We’re gonna need like 5 minutes. Nevermind whatever happens in these 5 minutes, we will be good.’ So we went on, and it took 8 minutes, instead of 5. But when we could laugh about it, it was funny. We looked like a couple and he was our child in the back.

Dudu leaving no crates untouched

O General comes up for some air.

Did having Eilon there as this third, kind of stranger, make any impact on how you and Victor got along? Did that impact how the two of you dug? Was there any pressure created by his presence?

No, at first he was really low maintenance, even though I called him Barbie. Traveling through these smaller cities we have to sometimes sleep in places that are not that great, and I think Eilon knows the deal so well and was trying to get the best without spending more, which is a great thing to do, but there were a couple instances were we couldn’t find a decent place to sleep. That worked out fine, but if there was any pressure at all it was me, like, ‘Man, we need to find something.’ So that’s why after we found some nice records, like sexy stuff to show off I was like, Okay, we’re good, and we’re gonna be able to find stuff. We had a lot of fun.

Well that’s good to hear, I think he had fun too, obviously. You mentioned that Victor did most of the research and I wanted to know how much research goes into a trip like this, and whether you mostly use the internet or word of mouth to find out where to dig.

I did a bit of research as well, but Victor, man, he did most of that. He started giving me paths and I followed through, but he has a bit more patience with that. What I mean is that, for a trip like this, he started about one week before looking only at the internet, using the criteria of what cities we wanted to stop at. We take into consideration the size of the city, we like medium-sized cities. The only time we stop in really small cities is when we get a vibe or some kind of signal that someone in that city is a record crazy person that accumulates stuff. If not, we just go, we don’t lose time. To get to Rio from São Paulo usually takes five hours. We took a week. We stopped a lot, there’s a lot of places to choose from. On the internet, I think that’s where Victor has a great mind. He diversifies a lot, he tries to think of different perspectives of where he’d be able to find record people. Not only people who are active with their own online shop, but those harder to get people. Brazil is very active in using Facebook groups, so you can get some leads there.

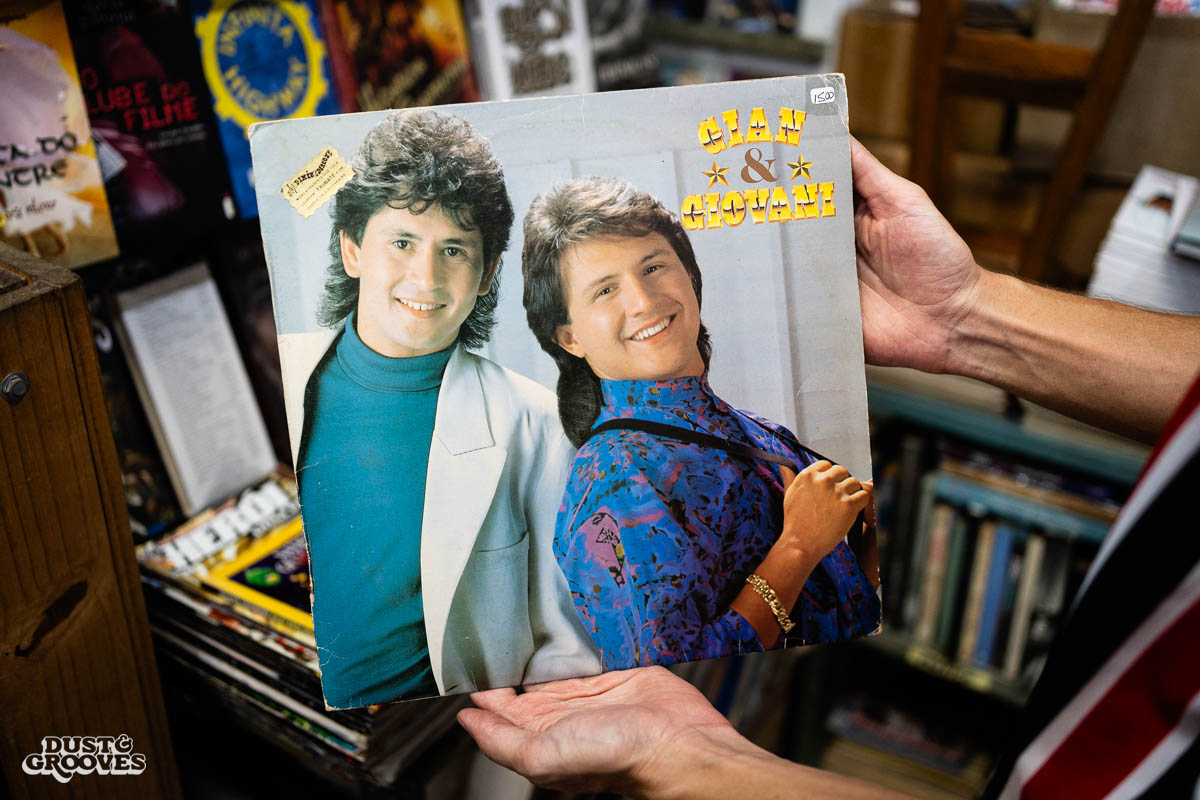

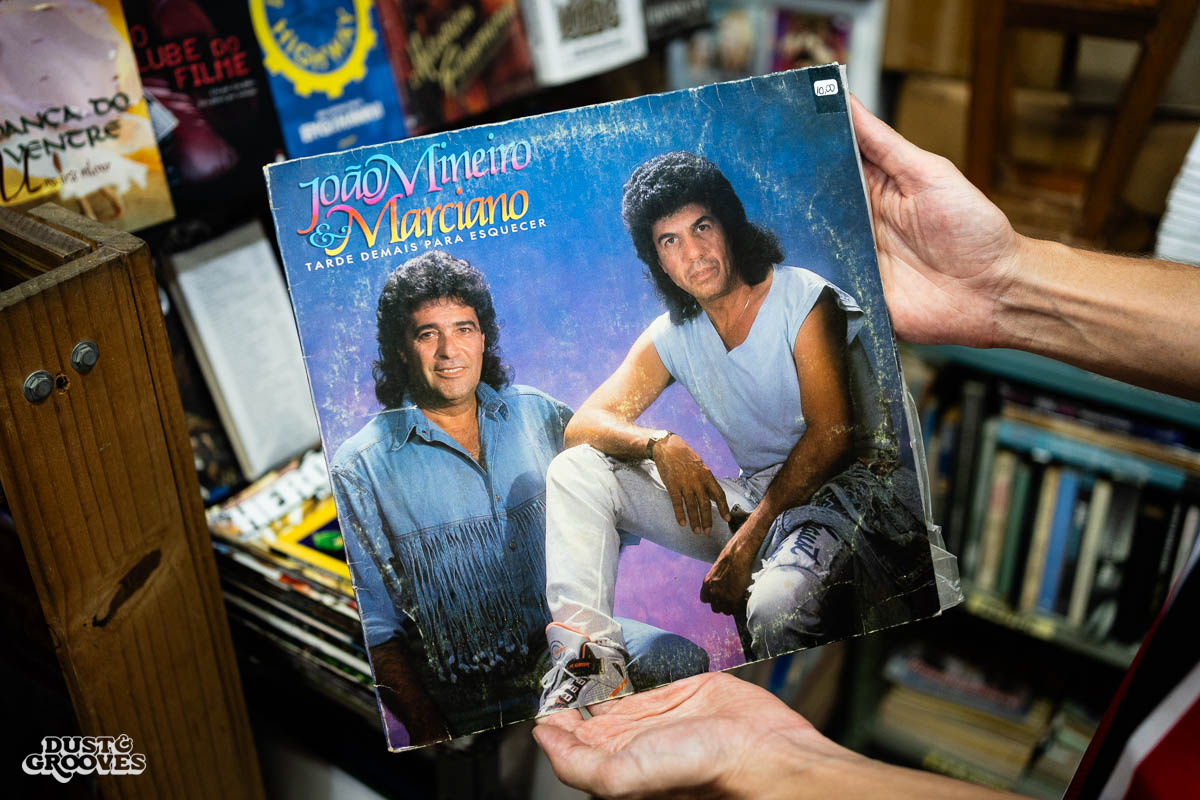

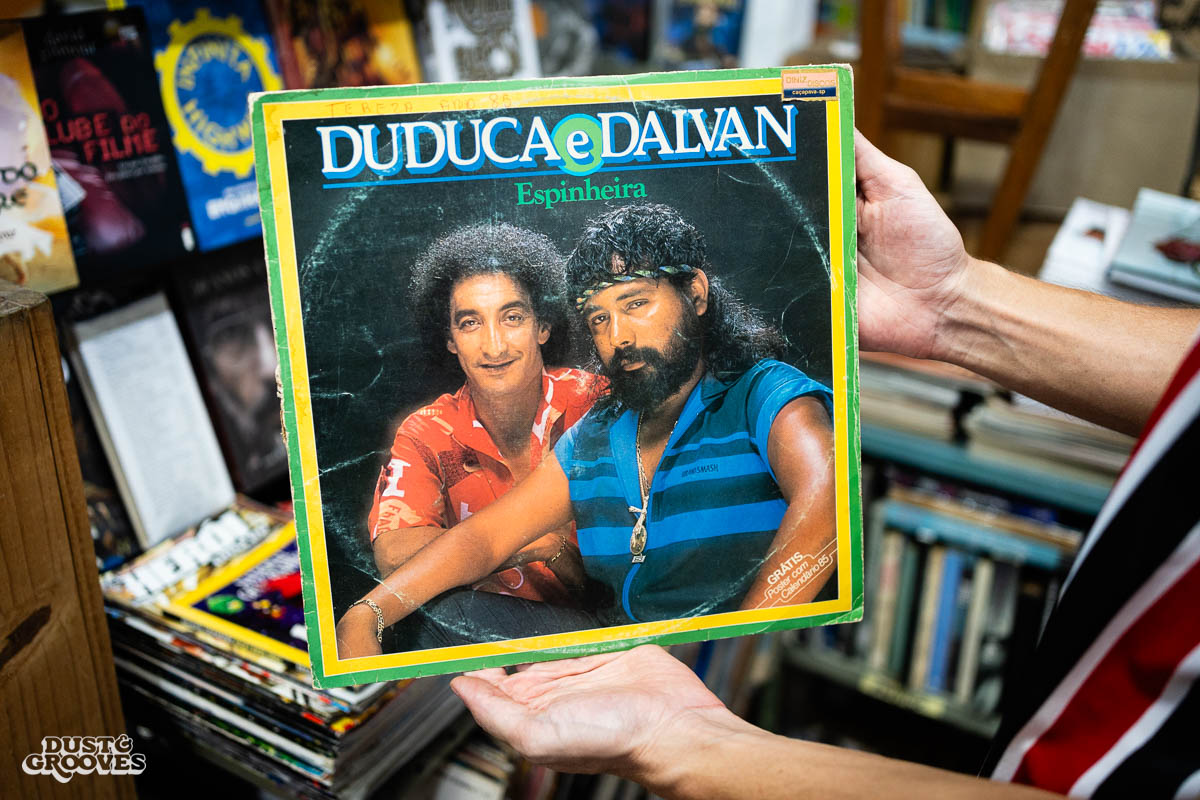

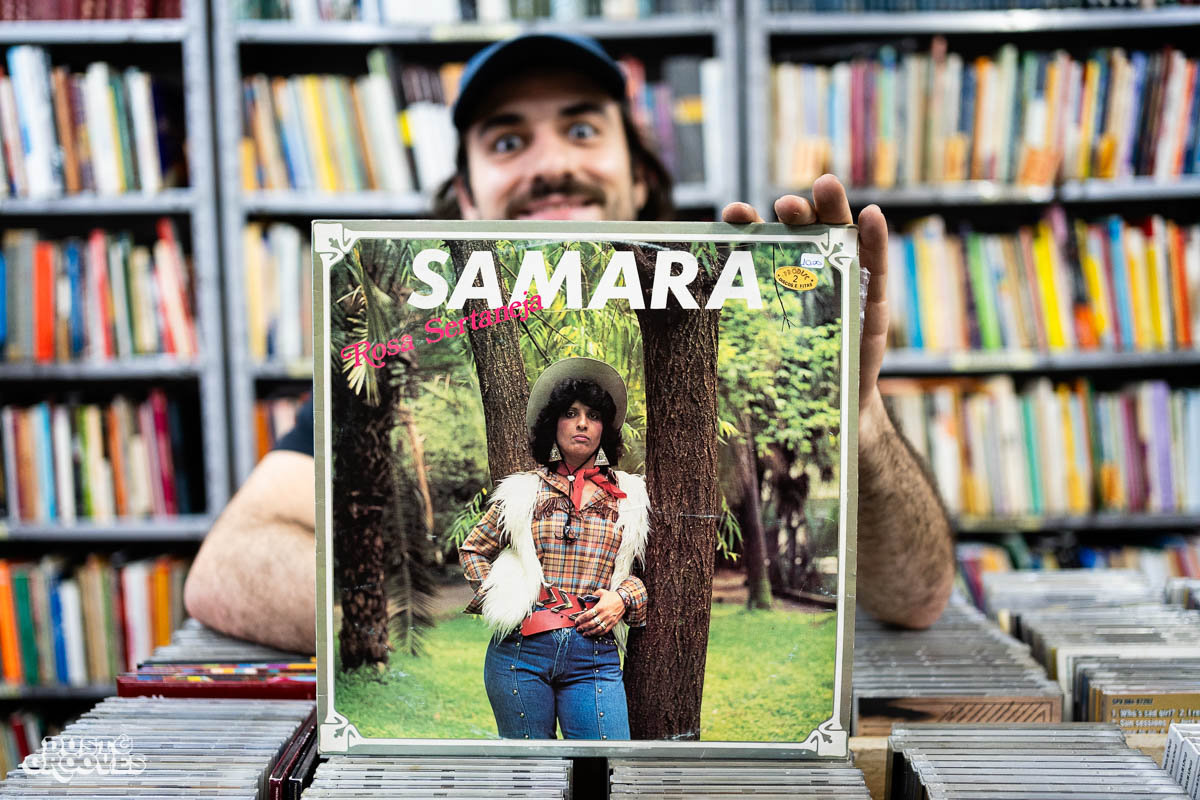

Mullets galore! Sartanejo music is full of beautiful duos, much like Dudu and O General.

Along a similar line, I heard somewhere that Brazil has been picked over, with all the record diggers flocking to Brazil to dig. Do you feel like that’s true?

I feel like that theres a lot of true to that, but we proved you can still find good records. Like everybody that’s into this thing of records, I have the same speech, like ‘Oh, I wish I started doing this before.’ I started flipping very recently and I’m not able to make a crazy lot of money on it, but if I’m able to do anything now, two years ago I would’ve been able to make a lot more. It’s been dug for sure, you can feel it sometimes when you go to places and think ‘Okay, nobody has been here, no way, this is butthole-nowhere’. Then when you look at the records you can feel it, like there was some good stuff here and now it’s only scraps. If it’s 2000 records and it’s only crap, somebody has been there before. I’d say the way to go nowadays is to really diversify your research. I don’t rely only on these trips…like I’m always actively looking on Facebook, I’m actively looking on Instagram. Here in Brazil we have a lot of dealing through Instagram, you find opportunities everywhere. And, try to broaden your knowledge of genres. You don’t need to like stuff to sell it. I deal with a lot of records I have never listened to fully, I just listen to parts to play test it.

It’s always a good idea to ask for records in furniture stores. This time in Jacareí, the owner looked at Dudu like he was from another planet.

That’s a great tip for how to find good places to dig. Once you actually find a place, what tips do you have for digging in those bins? Seeing things pass by, how do you figure out what you’re looking for?

It’s a no-brainer, just look into everything, don’t miss anything. Like the 7-inch I found in Aparecida. It was funny because we got into the guy’s house and he showed us a little cellar, with like 50 records. We looked for like 5 minutes, nothing. We were like, that’s it? Then he said, Actually, I have a bunch of my collection up there, but they’re not really for sale. You guys would have to convince me—that’s the words this guy used—you gotta convince me. ‘Okay, let’s look at it’ we replied. When we got there, he had his collection divided in two, the part that was totally untouchable, better not even look, and then the part that’s not for sale but “you could convince me.” We didn’t have all day, so we went really fast, but I found the 7-inch in a box in the middle of a room that had nothing to do with the other music I found. I could tell that someone had looked through the records but that box must have been forgotten because it’s a known sought and after record, it’s not hard to recognize.

O General and Dudu show some of their finds: Elis e Tom (1974) and Os Catedráticos (1972)

That’s a great story. Do you have any other particularly memorable stories from the trip?

I mean, I’m sure we are going to tell this in more detail, but by the middle of the trip we were almost getting to Rio, and we were mostly sleeping in not so nice hostels, like bed and breakfasts. One day, although, we found a very affordable, very nice, simple place on top of a mountain with a lot of nature—we loved that place. So Eilon woke up even earlier than us at like 6 am to run because it was nice. When you woke up it was this big, dense fog, and some horses just outside of our room had appeared. He was taking pictures of the horses and he went to take his run. Then, two days passed and we slept again in bad places. And that day Eilon was like, “Man, let’s try to find another place like that one, we deserve a nicer place, you know?”. ‘Okay, let’s do that’ we answered. We were in a not so nice kind of military city on the coast between Rio and São Paulo, thinking ‘There’s not going to be any nature or nice place here, let’s go to this little village on the bottom of like Penedo in the bottom of a big mountain, I’m sure they’re gonna have nice cottages and since it’s the off season they are probably going to look into filling the space.’ We go, but when we get to Penedo, the worst rain starts, really crazy, really crazy. We went to have dinner first and we found online a place in the mountain nature, not cheap but affordable for us that day. We were eating pizza and thought ‘Nice, we found a place!’. We finish and go up to the mountain, but it’s night, you can’t see anything and the rain is pouring down when we get there—everything’s closed and dark and doesn’t seem to have any concierge or anybody to talk to us. I said, ‘man, I don’t think it’s open’ but Eilon was not wanting to give up so we looked everywhere. I remember there was a very small pool already flooded from the rain and we really tried but there was nobody there. We got down from the mountain and found the first place we could find. The hotel we found had something to do with a train ride for children, so it was kind of colorful but it was very late at night and we were just wanting to sleep so we got the room. When we woke up, man. The place was for children and had a sea theme like SeaWorld. They had these janky statues of animals like spitting water into the pool, like a dolphin and stuff. I didn’t know this kind of place existed outside of Disneyland. So we woke up, we took some pictures of Eilon riding a dolphin, it was great.

Sounds like you were stuck in the Twilight Zone or something.

Yeah, I’m sure Eilon has the pictures that will illustrate it very well.

The Twilight zone hotel. Waking up at the waterpark hotel

On the trip, it seems like you met a lot of different people. Are there any favorite people you met while digging?

We are all going to give the same answer, and this is a good example of how we made connections on this trip. We went to a Sebo, which is a store that sells mostly used books, CDs, and records, but they make a living by reselling school materials. They had almost no records, but people in these small cities are really nice and love to talk. Victor is really good at talking to them. I can do it too, but I get more like a muppet—I get very excited and gotta move fast, whereas Victor takes his time talking to people. Sometimes it makes me crazy because I’m like, ‘Dude, stop talking about the weather.’ But it’s great because we started talking to the people at the Sebo and asked if they knew anyone in the city that has records. They told us about this guy that used to own a record store in the city, and that they didn’t know what he did with the records but they closed ten years ago. They said nowadays he owns a perfume store downtown. So we went to the perfume store and he wasn’t even there, but the worker told us no, he doesn’t have any records anymore, but he was a music lover. His name was Boeuri and we went to his house in the afternoon. He was by himself and older, like 60-70 years old. He got along really well with Victor, and he was an expert, even helping produce and support a specific music genre in Brazil called choro, which is a pre-samba style of music. It’s very good to play in bars here in Brazil because you don’t need a big group. The main figure in choro is Pixinguinha and people relate to him; he’s like a Brazilian Louis Armstrong. He was very important for this genre, him and Chiquinha Gonzaga.

Boeuri loved this music, and helped put choro music festivals together, so that was something that connected us. We started looking at his records and separating what we liked. I remember that because Victor is taller than I, he reached the top shelf and found a Clube da Esquina record and I was like, ‘Wow, shit.’ Boeuri started saying “Yeah, I have that, I actually don’t care that much for it but there was a time when everyone was listening so I had it.” Then he pointed to something else that he loved, a choro compilation. The market value was not much, but he loved it more than anything. We talked to him for a long time and he offered us a bit of coffee. When we were about to go we asked how much money he wanted for it. He was like, “No, no, you guys like music like I love music and I want to pass it along. I won’t charge anything.” That really broke us. I think he was the last guy we went to that day and then we went to eat, and I remember being like, what do I do? I can’t do that, I’m not gonna get these records and then sell them. Victor and I came to Eilon and told him we couldn’t flip the records, and he was like, “Yeah, you don’t want that karma!” So I told him, ‘Because Victor and I each had the record and we couldn’t sell it, to avoid any problems between us we’re going to give you the record.’ He was like, “What? I didn’t come for that, I came to document.” Every time we found something we wanted him to have he would be like, “Are you sure you don’t need this?” He was always careful about not getting in our way. The decision was the best one. Boueri is a very special person.

Boueri passing down the knowledge.

I love that story because the way that music connects us to each other is really highlighted, and now there’s a story behind them. Records with a story behind them are super special.

That’s the main thing, man, it’s the connection. You asked me about tips for digging, but I think in the end everything is about connecting. Nowadays, we are connecting through Facebook and all of that, and that’s cool, but when we are dealing with records it’s all about the digital and analog world. It’s so important to connect in person as well and take advantage of both universes.

One question I love to ask people is: Why, in this digital age, do people still want a physical record that they can hold in their hands?

I don’t know if I have much of a different input but in my opinion it’s pure fetishism. I was privileged that my parents had records at home and showed me so much good music, especially Brazilian stuff. I was lucky to be given all that knowledge. I remember there was a record they had that I was very into, probably prog music because I was very into it at the time, it was probably Genesis or something. But I listened to it on my iPod, and that’s where I had most of my deepest dives into music, with my headphones and iPod. At some point, you love that record so much that it’s weird having it just as some data, because it has the same emotional value as everything else. We desire a record because one can hold it, the music is physical, encrypted there, with the artwork and insert. It’s pure fetishism. We are anxious for a way to give more value to the music that is just abstract in the end. That’s how I see it, but my father and I argue about this all the time [laugh].

The end of our journey. The money shot in Rio