Listening to John Armstrong’s stories in his room, with open cupboards full of vinyl records and books, I found to be very inspiring. Mahogany-colored shelves stretched from wall to wall. There were two other rooms crowded with vinyl in his New Victorian house, most of them in boxes he “still needs to unwrap.” I knew immediately that this interview would travel into deep and wide landscapes.

John Armstrong started DJing in the 1970s while working as a lawyer at a Jewish law firm in England. While the other lawyers were off playing golf on the weekends, he was off playing records. They had no idea they were probably working with the first UK selector to present a fully focused tropical dance set—playing a mix of musical genres such as afro, zouk, Brazilian beats, kompas, reggae, dancehall, soul, soca, salsa, Afro-Cuban, hip-hop, jazz—even Punjabi bhangra for a while.

John has been playing records in and around London since the late ’70s, after a eureka moment attending one of the first New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festivals in the mid-1970s. There, he witnessed a rare and undocumented live show by Sun Ra Arkestra together with Olatunji’s Drums of Passion Orchestra on a riverboat—a performance that would become a defining musical moment in his life. John’s first DJ residency was at the Belsize Park Town & Country Club, followed by Greek Street’s Beat Route club and the Whisky a-Go-Go. In venues where prog-rock bands were flourishing, John was pushing records and sounds from the southern sphere of the globe to new ears—and hasn’t stopped since.

Over the last thirty years, he’s put together more than 200 compilations for both major and indie record labels such as Sony Jazz, BBE, and others—covering Latin, Afro, zouk, Brazilian music, soul, flamenco, Irish traditional music, and even rockabilly, cajun, zydeco, and rock & roll—making him one of the three or four most prolific compilers in the UK. He has lived in and around Hackney for the last thirty years and used to be a partner in the set up of the late lamented Institute Of Light multimedia hub.

This interview took place at John Armstrong’s house in February 2018. Expect to learn about the early dance music scenes in London, where Princess Margaret would spend her nights dancing, and how John creates his heartfelt compilations.

“The lovely thing about an LP is what it says about the artist. You pick it up and there’s a beautiful picture and you start thinking ‘what is he doing there?’ about the musicians. You can hold it, which you can’t do so much with a CD.”

John Armstrong Tweet

What’s playing right now on your turntable?

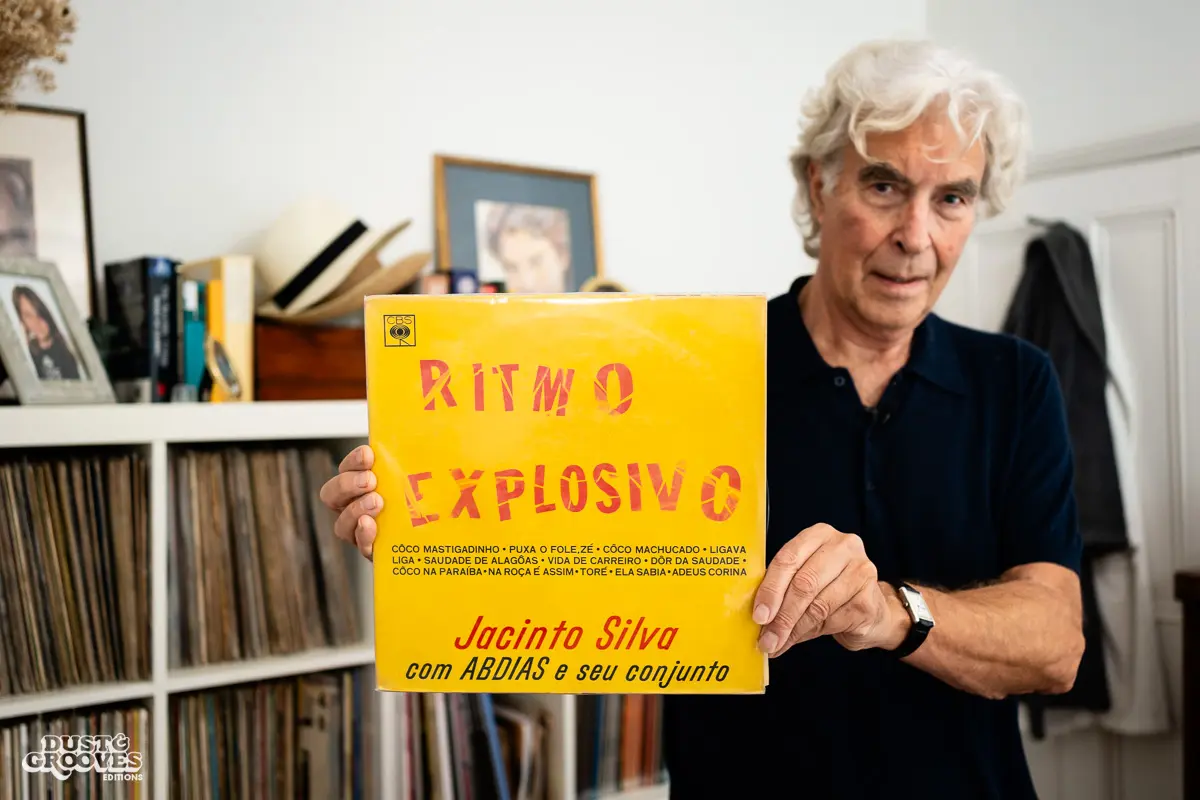

Ritmo Explosivo by Jacinto Silva. It’s a wonderful mid-1960s forró/balanço/coco LP from Alagoas. I’m obsessed with and in love with 1950s and 1960s forró. It’s like a window to a forgotten time and place.

Who’s responsible for your passion for music?

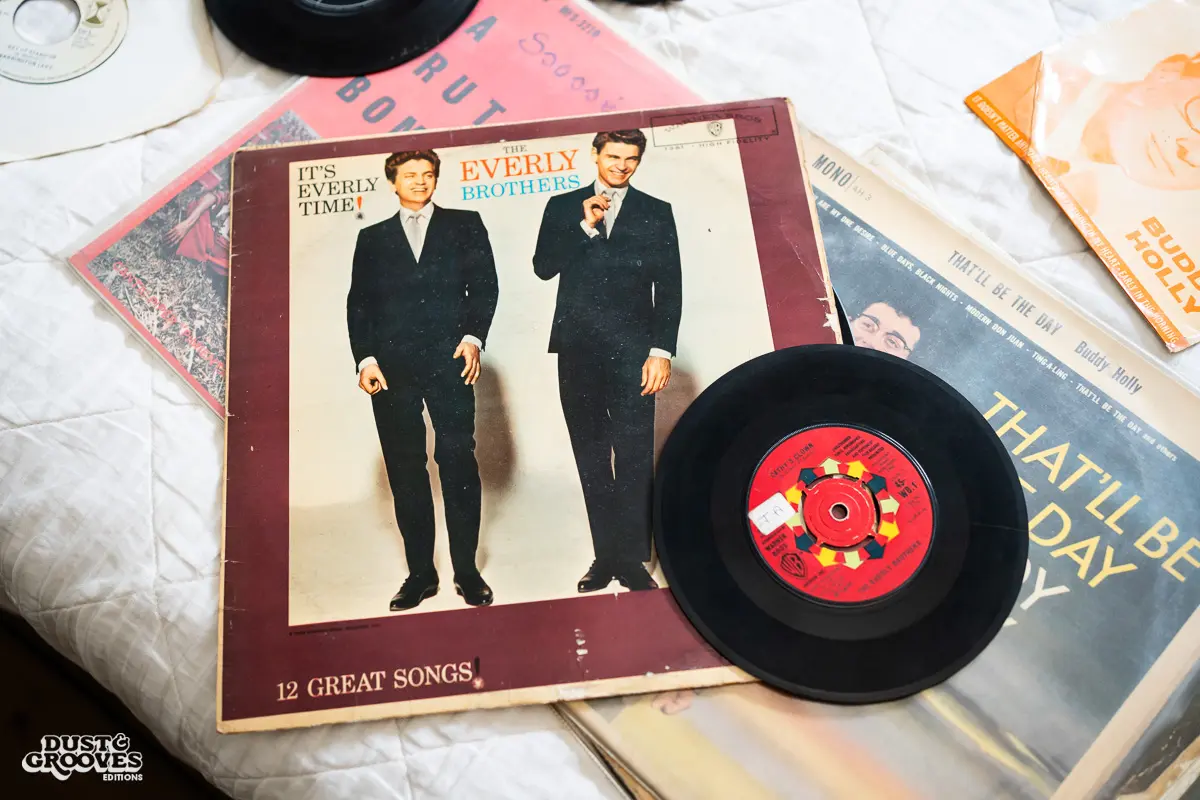

My older cousin Richard (now sadly deceased) had piles of 78s by Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran, Little Richard, the Everly Brothers, Frankie Lymon, etc. He generously let his pesky little cousin (me!) play them over and over.

A Teddy Boy [young British rock ’n’ roll enthusiast] called Mike Healey lived a few doors down from my childhood home. He was a few years older than me and my best friend Martin. He wouldn’t let us into his house, but he’d open the window at the back and we’d have to stand in his garden while he played his 45s: Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, Elvis, Eddie, Buddy, etc.

And my dad, who wasn’t exactly a collector, bought a fair few records—mostly classical music and Broadway musicals.

Jacinto Silva — Ritmo Explosivo. “I’m a Brazilian freak, no doubt about it. I love all styles, but over the last ten years or so, I’ve become obsessed with collecting 1950s through 1970s forró. Hard to find even in Brazil, where true ‘forrozeiros’ are like United States doo-wop collectors: they know who’s got the ‘only copy’ of which record.”

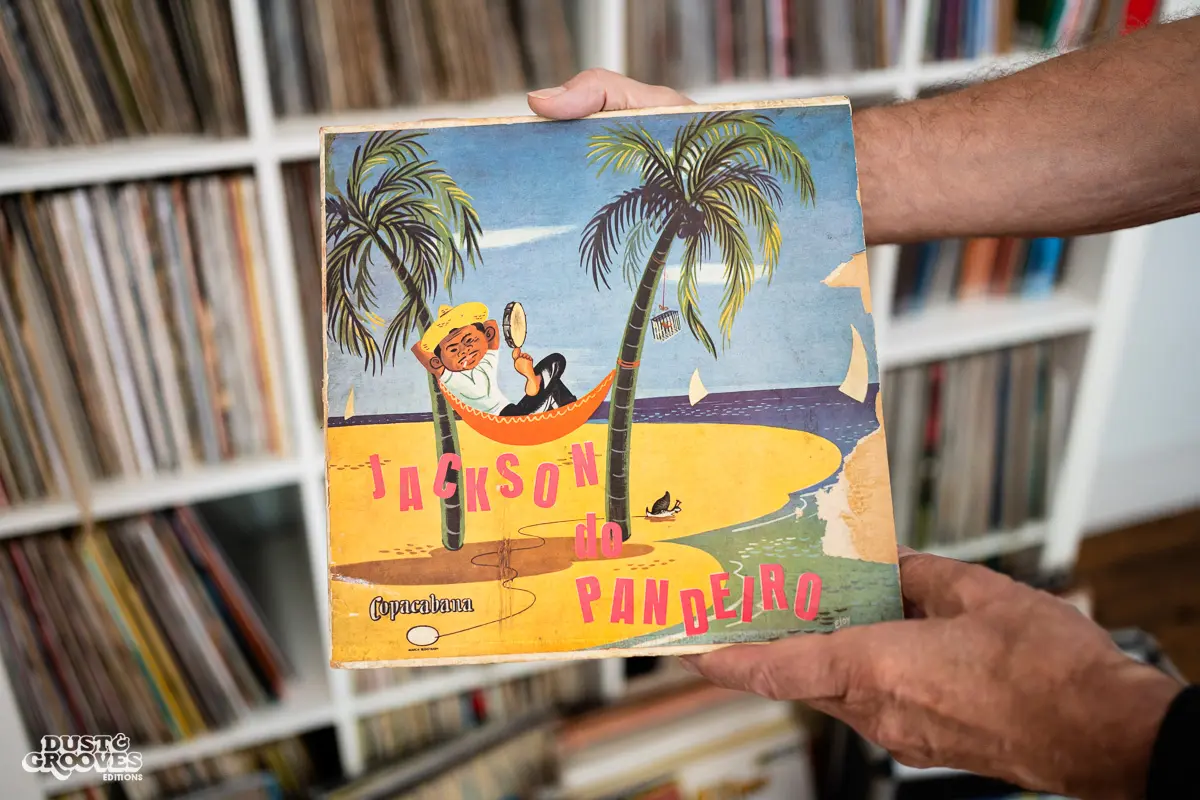

Jackson do Pandeiro – Com Conjunto e Coro. “The great king of ‘balanço’ forró, Jackson do Pandeiro. Very happy with this original 10-inch.”

What was the first record in your collection? Do you still have it?

It’s Everly Time by The Everly Brothers. I still have it and play it occasionally—perhaps the world’s first country rock LP!

Is there a record you used to play over and over again as a kid?

Fats Domino – Whole Lotta Lovin’ from the 1950s. When I was a kid, when you were invited to someone’s birthday party, you took your most recent singles and played them. And make sure you take them back by the end of the night, and write your name on them.

I remember I had a friend—he’s a well-known actor called Jim Carter, the guy who plays the butler in ‘Downton Abbey.’ He had an older brother who was buying records before we were, so he had a very big collection. We’d have these Coca-Cola and coffee parties, and we’d all bring our own records. The really funny thing was, just the other day, I found a record I’d forgotten I had with JC Carter’s initials on it. I must have pinched it in 1964 or something like that. I told Jim about it, and he said he wants that back…

What was the most influential record for you, personally and professionally?

Very hard to say. I was a keen finger-style acoustic guitarist in my teens and favored blues, jazz, folk, etc. Folk Blues & Beyond by Davy Graham was probably the record that first made me realize what a big world it is, musically. Along with blues, folk, and jazz, Davy was adapting Indian, Arabic, African, and gypsy music to acoustic guitar. With unusual tunings, he was doing “world” music about twenty-five years before the term was coined.

Then there was Nick Drake’s Five Leaves Left, which I still listen to regularly. And of course, Pet Sounds by The Beach Boys, which just blew me away. I was never much interested in The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, or that whole British beat-group thing at the time—although I came to appreciate them later in life.

The Everly Brothers – It’s Everly Time / The Everly Brothers – “Cathy’s Clown”. “My first ever records: birthday presents at 10 years old, to go with a brand new RGD record player. The Everly Brothers’ beautiful collaboration with country songwriting team Felice and Boudleaux Bryant, and the 45 is ‘Cathy’s Clown.’ The Buddy Holly is from 1957 and predates his ‘sweeter’ sound—though I love that too.”

What were your early musical influences? What did your parents listen to?

My mother was a very happy and sociable person. My father was an intellectual—he liked big Broadway musicals, and he could tell who was in each one.

If he ever got the chance to go and see a show, I would go as well. I didn’t like it much, but he knew every word. He came from that generation of working-class London, and when he was a kid, he went to musicals with my grandfather. They would go to these big dodgy halls behind bars where they would have sing-songs and comedians who had an act with dogs and juggling. There would be some impressions, maybe a magician too. It was around the 1930s–1940s.

The television finished the music halls, really—these guys had one act. I suppose I’m the way I am because of who my parents were.

Eddie Cochran – The Eddie Cochran Memorial Album. “Another one of my first-ever LPs. I loved Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, and Jerry Lee Lewis—mainly because they were all predominantly singer-songwriters, unlike so many manufactured pop idols of the time. As I grew older, I extended my allegiance to The Beach Boys. Never was a big fan of UK music of that time—the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, etc.—although I like it now. I was probably doing that adolescent ‘trying to be different’ stuff, I guess.”

Buddy Holly – “That’ll Be The Day”. “I love Buddy Holly.”

"After years of looking through records, you can sort of tell what the selection is going to be like from the first 50 LPs or something. It's just a 'feel' from experience!"

John Armstrong Tweet

Richie Havens – 1983. “I love all Richie Havens’ output, but this double LP takes the biscuit. Folk-blues live versions of Beatles etc., and his version of Donovan’s ‘Wear Your Love Like Heaven’—one of the most transcendentally beautiful acoustic arrangements I’ve ever heard.”

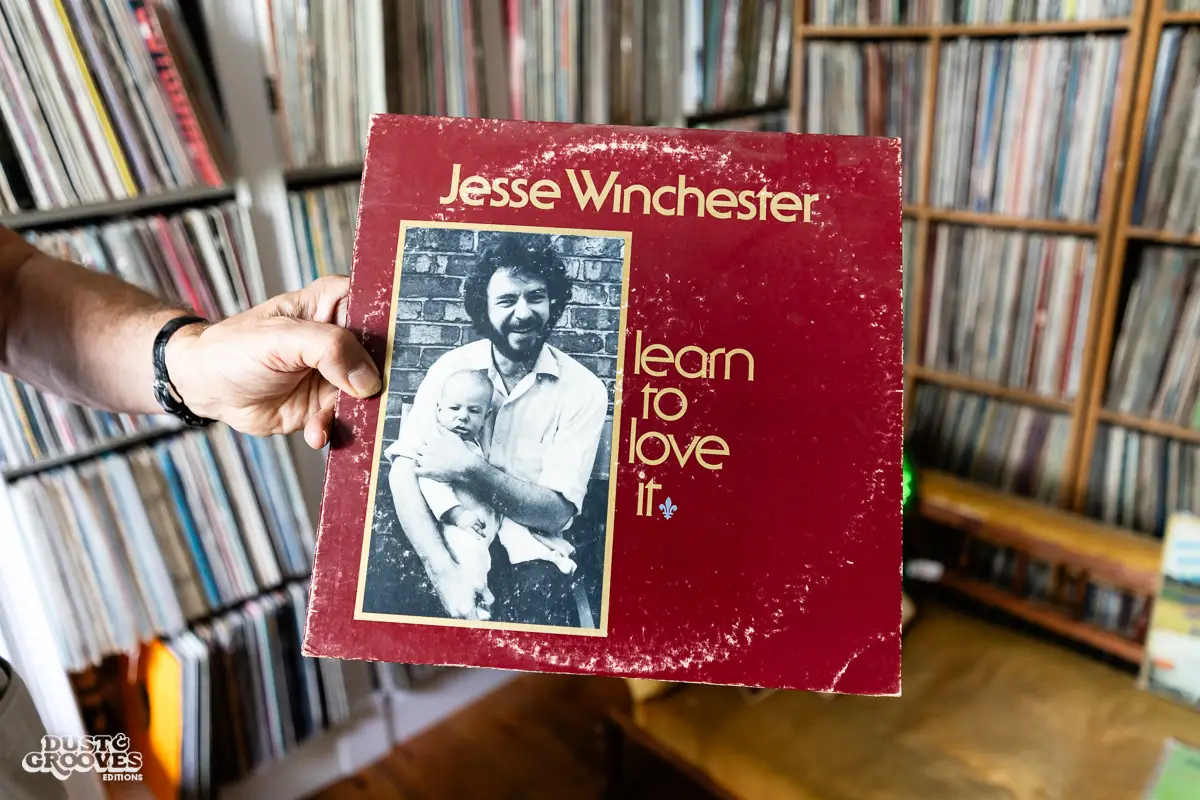

Jesse Winchester – Learn to Love It. “Two reasons for this: first, the late Jesse Winchester was/is my favorite American acoustic singer-songwriter by a country mile. Second, I distinctly recall buying this disc on the day I finally gave up cigarettes. You don’t forget an event like that in a hurry.”

Bert Jansch – It Don’t Bother Me. “The first girl I ever loved—I mean really, really loved—was a big folk fan, and so we listened to a lot of these artists’ records together in the mid-1960s: Paul Simon, Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, etc. This is the late Bert Jansch, a wonderful, weird acoustic guitarist with a unique ability to make ‘old’ traditional folk songs sound new. Others like this were Jansch’s Pentangle colleague John Renbourn; the Canadian (brief) ex-pat Jackson C. Frank, whose tragic life is mirrored in his classic ‘Blues Run the Game’; and the amazing Davy Graham—who played world music at least twenty years before the genre was invented in a North London pub by a group of record label owners.”

Career-wise, it really began when I started DJing African, Latino, and Caribbean music in 1980 in London. Before that, I’d mostly specialized in soul, vintage R&B, rockabilly, and reggae—but there were several records that still stand out in my memory as game-changers.

Groundbreaking zouk records such as Jacob F. Desvarieux / Georges Decimus by Jacob F. Desvarieux and Georges Decimus, or the grand soukous Franco et Son Tout Puissant OK Jazz – Mario by Master Franco. The classic reggae record “Get Up Stand Up“ by Barrington Levy, and the Gabonese album En Verve by the important group Massako. The Brazilian band Os Novos Baianos with their album Acabou Chorare, and the guaguancó record El Grande by Fruko from Colombia. Gouye-Gui National by Orchestra Baobab, a Senegalese band active in the 1970s–1980s and now again. And Yebo Edi Pachanga Peuple by Orchestre Tembo—a rumba record from the late 1960s.

Hundreds more, but these are just the ones that came to mind quickly from that time, as having something new, unusual – usually in the production values, I must admit.

Georges Decimus – La Vie. “I still remember my initial exposure to the magic of zouk. I was with my dear friend, New Orleans filmmaker Jason Berry, in the Paris club Chapelle Des Lombards, at about three in the morning in 1982 (long story). The brilliant DJ, a Guadeloupean guy, had been playing a great mix of soukous, rumba, konpa, cadence, salsa, etc. all night… and suddenly, he dropped a white label. It was this: La Vie by Georges Decimus, one of the three founders of Kassav’, the kings of zouk.”

Barrington Levy – “Get Up Stand Up”. “So many great reggae pre-releases to choose from, but I go for this one every time: the digital version of Sir Bob’s ‘Get Up Stand Up’ by Barrington Levy. It’d be easy to get this classic badly wrong, but Jah LifeTime producers Horace Wright and Philip Chin have a wonderful collective ear every time, preserving the majesty of the original but with a sense of urgency and aggression that hits straight home to the dancehall.”

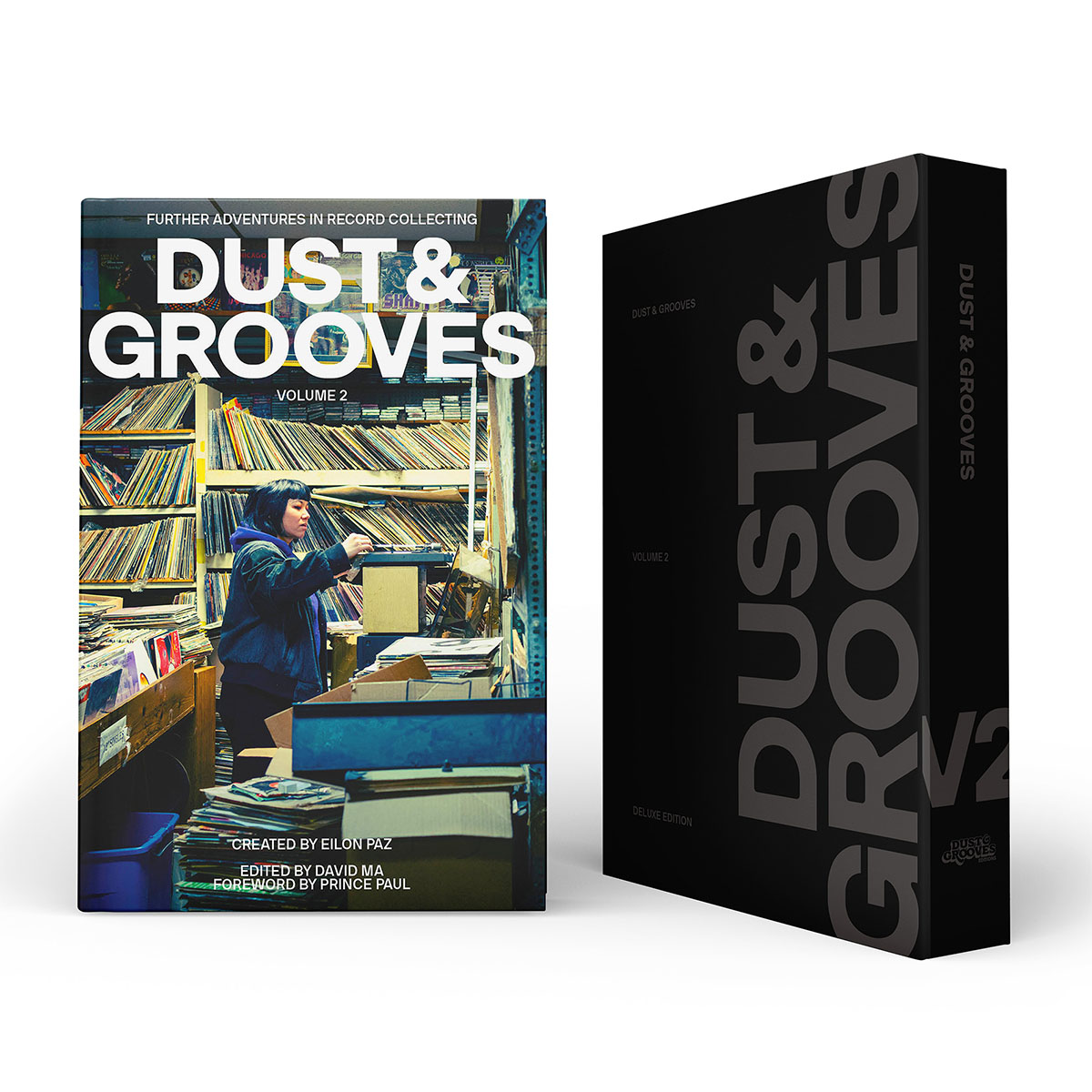

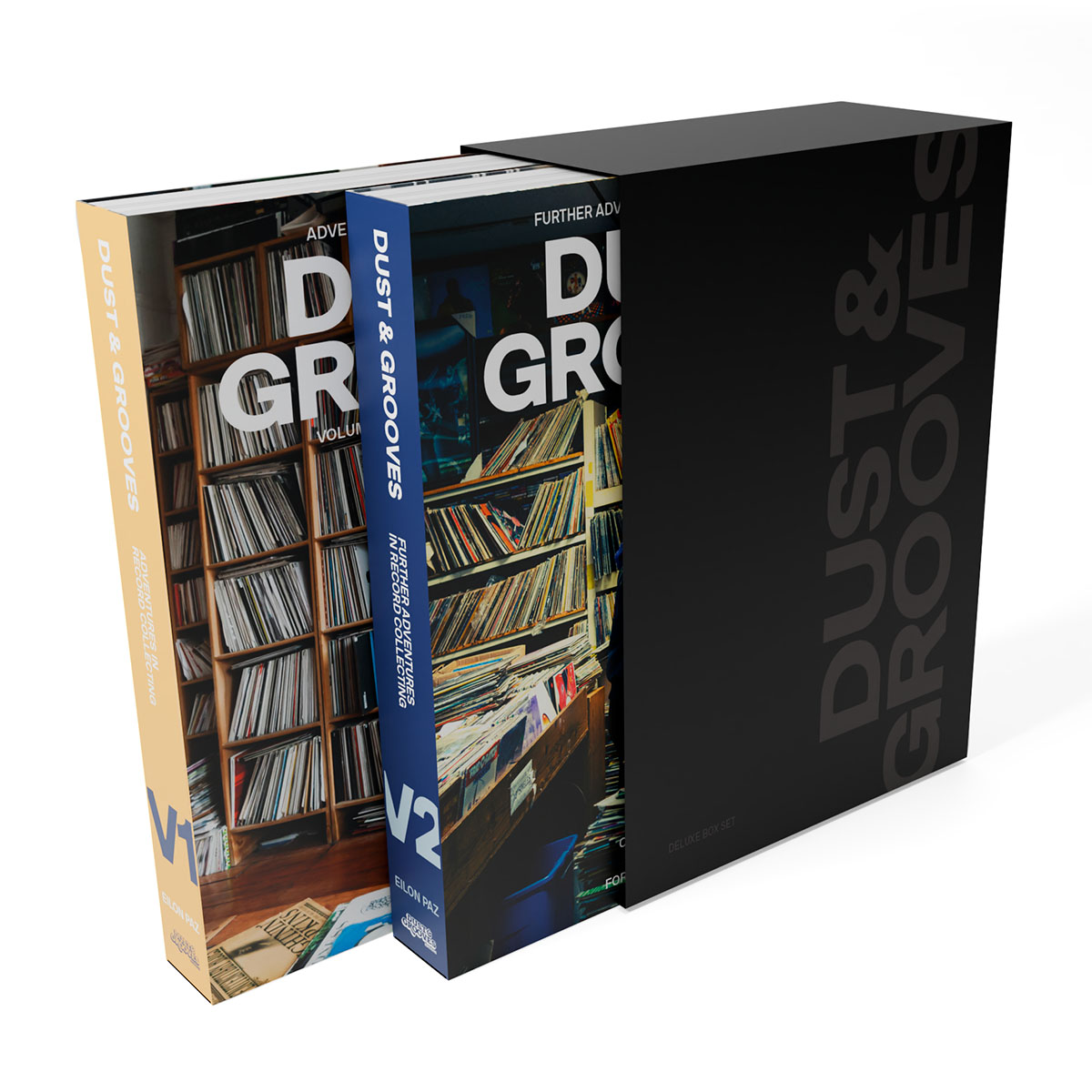

Further Adventures in Record Collecting

Dust & Grooves Vol. 2

John Armstrong and 150 other collectors are featured in the book Dust & Grooves Vol 2: Further Adventures in Record Collecting.

Where do you buy your vinyl these days?

Everywhere and anywhere.

Is there a holy grail record that you still cannot find?

Not really. But there are records that I wish I’d never sold—for example, a couple of funk-soul records from the late 1960s like Helene Smith Sings Sweet Soul on Deep City and “Ain’t Nothing You Can Do” by Joe Matthews on Top Kat. Some Boogaloo records like “Lose It Before You Lose It” by Bobby Valentin on original gold Fania 7-inch and That Booga Mambo Beat by The Steve Hernandez Orchestra…and others!

What’s your comfort record?

My comfort records vary from time to time, year to year, season to season! Currently, I have two, and they’re both by The Danish String Quartet, Wood Works and Last Leaf . They’re unbelievably beautiful string-quartet renditions of traditional Danish & Faroes airs and melodies.

Currently, I’m also loving Leonard Cohen’s very last record, You Want It Darker, for when I’m feeling a bit contemplative!

Do you still consider yourself a record digger? Do you still have the time, energy, and passion to go digging for records?

I visit Brazil often because half my family is there, so I do some digging there. I do get bored fast these days—but not always. After years of looking through records, you can sort of tell what the selection is going to be like from the first fifty LPs or so. It’s just a feel from experience!

Giovana – Quem Tem Carinho Me Leva. “Giovana—one of the lost greats of carioca samba negra.”

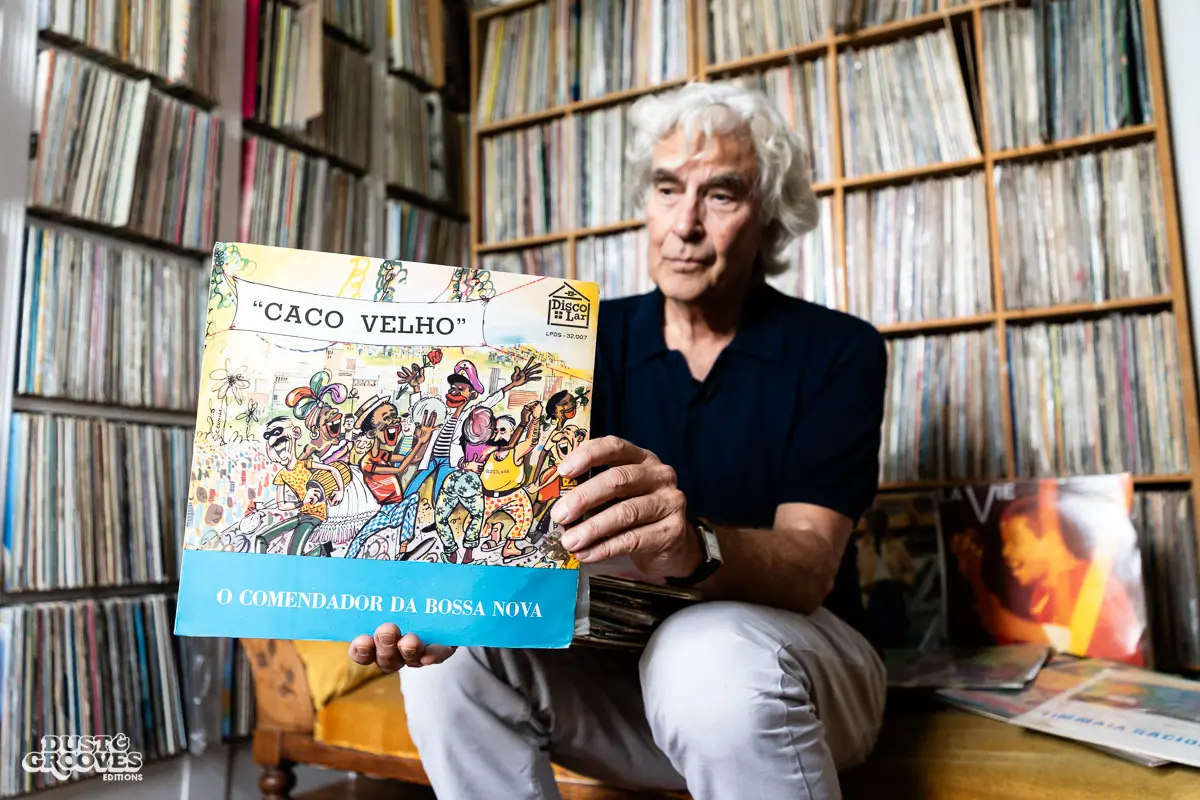

Caco Velho – O Comendador da Bossa Nova. “There’s a story that João Gilberto, when he couldn’t get any dates in Rio when first starting, went down to Porto Alegre to clear his creative head; hooked up with cabaret pianist/double-bassist/singer/writer Caco Velho, and ‘borrowed’ a few ideas. I make no comment, but listening to Velho’s one LP, and a couple of singles, I can see where the rumors started.”

I don’t really dig much anymore—except, say, if I’m in a new place, like when I visited Uruguay, where the selection was completely different from what I’m used to in Europe, the US, and Brazil, which were my usual places to dig when I was younger. These days, I listen more to CD-only releases from the 1990s and new stuff online when it comes to African, Brazilian, etc. Along with about forty thousand LPs and singles, I have around twenty thousand CDs—that’s a whole different scene. There are lots of Congolese, French Caribbean, soca, Cuban, and Brazilian records that are CD-only from the 1990s—not online or on vinyl. I predict that CD digging will become a thing soon!

Was there a compilation you bought that inspired you to start creating compilations on your own?

Not particularly. I sort of came into doing compilations after I’d already been DJing for some time. I began to get a bit of a name for myself, for playing particular kinds of music, and then I began to get approached by record companies. To be honest, there weren’t many compilations around in the mid-1980s. It was something quite new for us, as only around the late 1980s did people from all over the world start coming to London.

Take us through your process of working on a compilation.

I start with a completely open mind. I usually have a hit list of tracks. For instance, something I’m working on at the moment—a South African 1980s synth-disco set—I had all those records back in the 1980s. Some of them I’m not crazy about, but some I love.

I used to have a thing with a DJ from Harare, Zimbabwe. He would request Michael Jackson promos, so I would send them to him, and he would send me all of Zimbabwe’s and South Africa’s promos. At the time, we knew about Zimbabwean music, but we didn’t know much about South Africa. The South African synth stuff—these were younger musicians who were listening to American productions. And that’s what it’s all about. And now, suddenly, it’s very popular again.

Various Artists – Highlife Time! / Tabansi Studio Band – Wakar Alhazai Kando / Zeal Onyia – Return of the Trumpet King. “Another selection of my curated reissues, for which I also wrote the liners. The double LP Highlife Time! was one of Spanish label Vampisoul’s early releases, while Wakar Alhazai Kando and Return of the Trumpet King are both part of the marathon 40-LP reissue series of Nigeria’s Tabansi label by Peter Adarkwah’s BBE Records.”

Nzimande All Stars – Highway Sporo Disco. “I compiled a track off this great Mzansi funk and disco LP for a 2009 compilation, John Armstrong Presents South African Funk, and did a disco edit for Sofrito Records at the same time wearing my edit hat, ‘Kilombo.’ I still play it often.”

“In 1968, we hitchhiked down to Morocco, and we crossed through Algeria, and we went to the English embassy in Tangier. We asked them if it was possible to hitchhike the Algerian desert when the war was on and they said we were crazy. We did it.”

John Armstrong Tweet

How do you find someone to publish the compilations you’re interested in publishing?

I’m lucky enough that I know a lot of record labels, so I just reach out to them. The biggest problem always—for instance, with the South African synth compilation Yebo! on BBE, released in June 2023—is that the really good ones were originally on Gallo, but they sold all of their stuff to Universal.

We were very lucky with Urgent Jumping, a comp of Kenyan and Tanzanian classics for Sterns records, because they already owned all the tapes—they had bought a whole lot of tapes from a Kenyan guy, and they just sat in the basement doing nothing for years. We didn’t have to license anything, so we had our pick.

It also went well with Brazilian major companies when I was the music consultant for Fatboy Slim on his Brazilian remix compilations a few years ago. I was kind of the Brazil music input guy, and he was like, “Yeah, I like this track, I like that track,” so I was the first input, really.

Do you fly over to these countries in the process of creating a specific compilation?

For me, it’s the other way around—I’ve already been there, and when I come back, someone asks me if I want to do a compilation.

So in terms of digging, I’ve done all of that—years of that. But I don’t do it so much anymore. I was traveling all over Brazil in the 1980s and 1990s, so I don’t really need to go back. Whenever we visit my wife’s family in Brazil—I go there all the time—I don’t need to actually make a journey out of it.

For the Urgent Jumping compilation, it all started after the tour I did with Kanda Bongo Man in East Africa. I used to be booked quite a bit in Africa and the Middle East, in Oman. I got to tour for four weeks with the musicians of Kanda Bongo Man, so it was great.

What is your take on the way the European crowd perceives music that was created in Africa?

It is very aspirational music, and also sometimes has a humorous way to it—that kind of humor doesn’t always translate to European ears.

That’s actually what I’m trying to do: open people to this understanding of how we can learn from this attitude toward music creation. Also, in terms of the scene, you will be taken seriously only when you play dark sounds.

I think it’s a lot to do with our history. The non-African, non-African-American view of Black music has often been: “If it ain’t sad, it’s bad!” We saw this with blues—white folks jumped first on the sadness, the melancholy of the music, without also celebrating the wide-ranging feelgood, humorous, satirical, romantic, etc. side of blues, as well as soul and funk. And I think that this has partly overlapped into the way non-Africans appreciate African music.

For example, Fela Kuti’s lyrics are deliberately angry, satirical, political, and activist, and he deliberately sings everything in pidgin so both West Africans and non-Africans can understand. I think the casual non-African music listener therefore assumes that all “good” African music is angry and polemical like that—which, of course, it’s not.

The continent is full of beautiful gospel and Muslim praise choirs and orchestras, cheeky playful humour and satire, ecstatic music of love and romance, storytelling tales not too far different from classic country & western. I remember working briefly in a Soho record shop occasionally, just to help the owner out now and then in return for a few promos. I recall one or two customers coming in asking for African records—“but not those cheesy calypso-type happy stuff… I want more political-type stuff.”

I knew immediately they wanted Fela but not, e.g., Franco & OK Jazz. Franco’s lyrics are just as critical of politics as, say, Fela’s, but because Congolese rumba is in Lingala—which 99% of non-Africans aren’t familiar with—and makes wide use of happy major keys and Latin dance rhythms, many newcomers assume the music’s not serious.

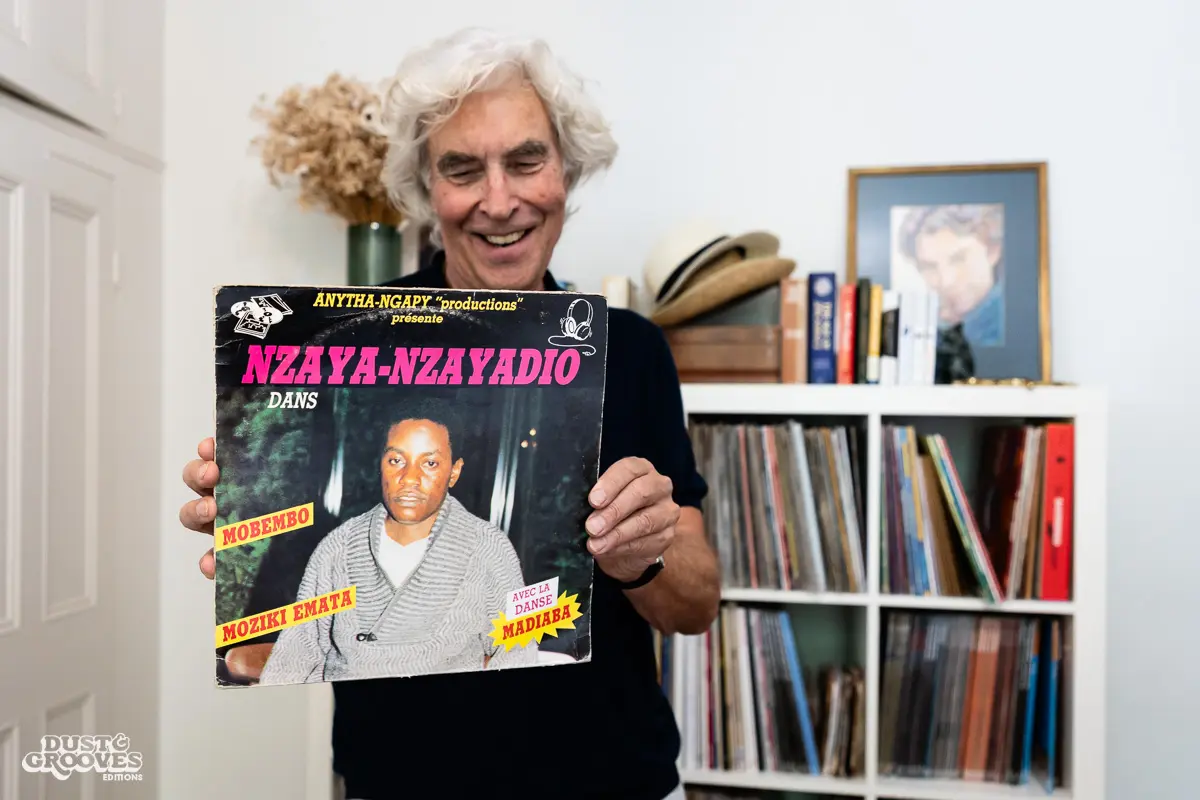

Nyaza Nyazadio – Mobembo. “If you were to ask me my favorite genre—of African music—of all the wonderful music that the continent and its diaspora create, I’d have to say Congolese rumba, soukous, ndombolo, and all versions thereof. This is just one of the hundreds of beautiful Congolese recordings that I enjoy. Not a particularly rare record, but a beautiful one, which is what really matters.”

“The first time I heard a Congolese record, I didn't quite get it in the beginning. But slowly, you begin to get it. And now, if you said to me, ‘Let's put on an African record,’ I’ll go straight to a Congolese record.”

John Armstrong Tweet

Actually, the first time I heard a Congolese record, I didn’t quite get it in the beginning. But slowly, you begin to get it. And now, if you said to me, “Let’s put on an African record,” I’ll go straight to a Congolese record.

Sadly, Congolese music here is still very poor in relation—Afro-funk is working more here. I think this music is aimed at people who are not very interested in African music. That’s aimed at house DJs, disco DJs who want to be able to drop a record in a set and give it a different sound.

Maybe it all started when Bob Dylan suddenly went electric—“No, Judas!” they all shouted. “If it’s to mean anything serious, it’s gotta be acoustic and non-commercial-sounding!” Total nonsense, of course—but there it is.

Hugh Masekela – Self-titled. “I was DJing African music in the early 1980s, and who should walk in but Hugh Masekela and his lovely wife! Masekela and I got chatting, and he asked if he could look through my records. He found this and couldn’t believe it: ‘I haven’t even got this one myself anymore,’ he chortled. I immediately offered the record to him, but he said, ‘Naw, you keep it, man, you’ll make better use of it than me.’ Lovely guy. So sorry we’ve lost him.”

In reviewing your body of work—producing over 200 compilations—would you like to share your motivation? Is there a cause?

When creating a compilation, you have to do this leap-of-faith, mind-reading thing where you hope that somebody is picking up the record will like the tracks. Sometimes I see myself as a selector: I play one record that I like, then another that I like, and I try to make them tell a story.

I’ve gotten it wrong a couple of times. There was one review of the East African compilation—he wasn’t a specialist, but he was a New York Times reviewer. He gave it a good review, but he said, “I can’t help but feel that this guy is almost too much into the music to be able to communicate it to someone like me who knows nothing about it.”

I took that criticism on board—it’s something you need to watch out for.

You can’t be too detailed, you can’t be too specific. Sometimes I think it’s best to just do the compilations—here are the artists, these are great records. If you want to know more about it, just go to the internet.

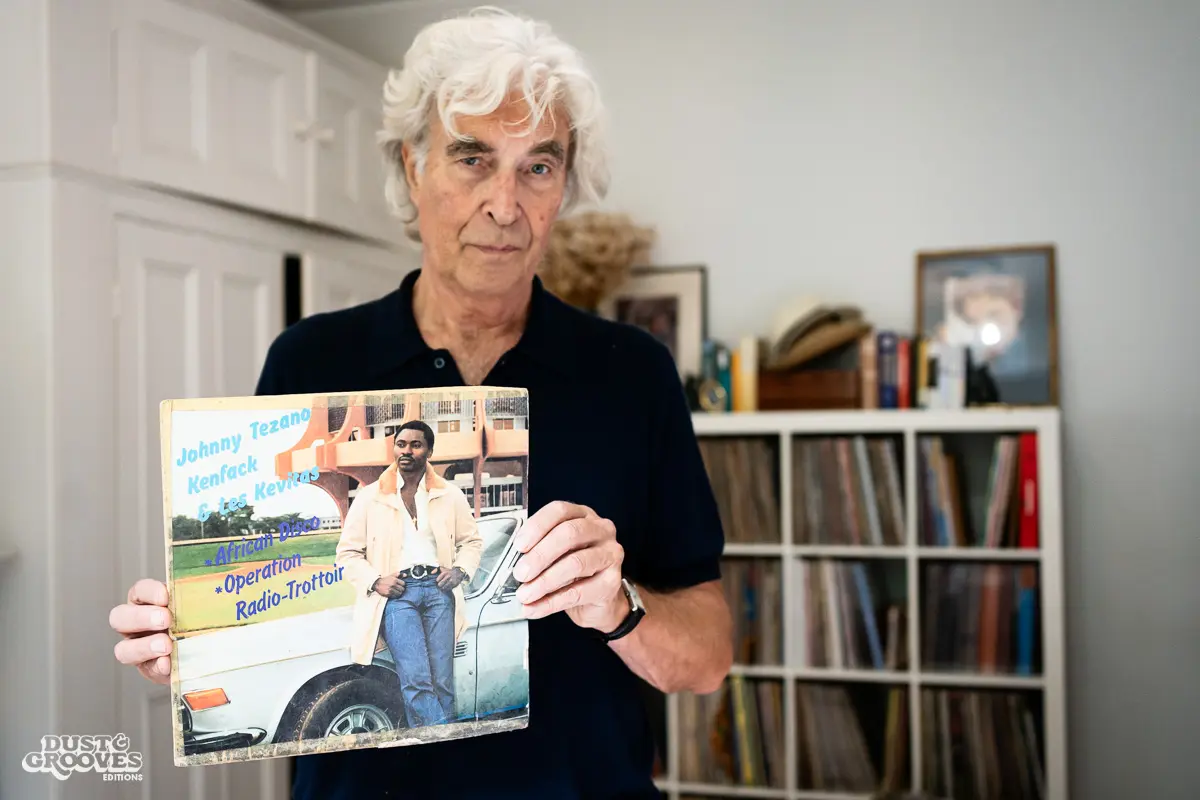

Johnny Tezano – Competition Pour Kumba. “Cameroon has its economic problems these days, sadly, but it was seen as one of West Africa’s biggest success stories when Johnny Tezano recorded this record around 1978—the tune ‘Competition Pour Kumba’—a success story for the one-time ‘Cameroonian city of the future,’ Kumba.”

What are some game-changing experiences that left an impact on your career?

There were a few. The first one was at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, which started in 1972 and is still going today annually. It’s by far the most popular music festival anywhere in the world, in a class of its own.

I was there in the late 1970s a couple of times, when it was still quite a small enterprise: people were expected to collect litter as they left the festival site, take their empty beer cans home—all that Woodstock-type hippie stuff. It was very cool.

But the music! The first year that I went—just a selection: Earl Hines, Professor Longhair, the Neville Brothers, Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, Al Green, Herbie Hancock, every cajun and zydeco band you could think of, an African griot storytelling tent; and jazz-wise: Betty Carter, James Booker, Sun Ra, Olatunji.

I particularly recall a riverboat all-nighter (a live concert on a riverboat going up the Mississippi) featuring the Sun Ra Arkestra and Olatunji’s Drums of Passion Orchestra. They played separately, then together—all of them on stage. Never been done before or since. It wasn’t filmed, and there is no record except memory—and it was one of the defining musical moments in my life. Suddenly, Sun Ra’s weird music-noise coupled with Olatunji’s African drumming all seemed to make perfect sense!

I was also there to interview many people: Dr. John, Allen Toussaint, Johnny Adams, Betty Carter, Lee Dorsey, Bobby Bland, and B.B. King—all of whom were playing. Up till then, these amazing musicians and artists were just names on record jackets for me.

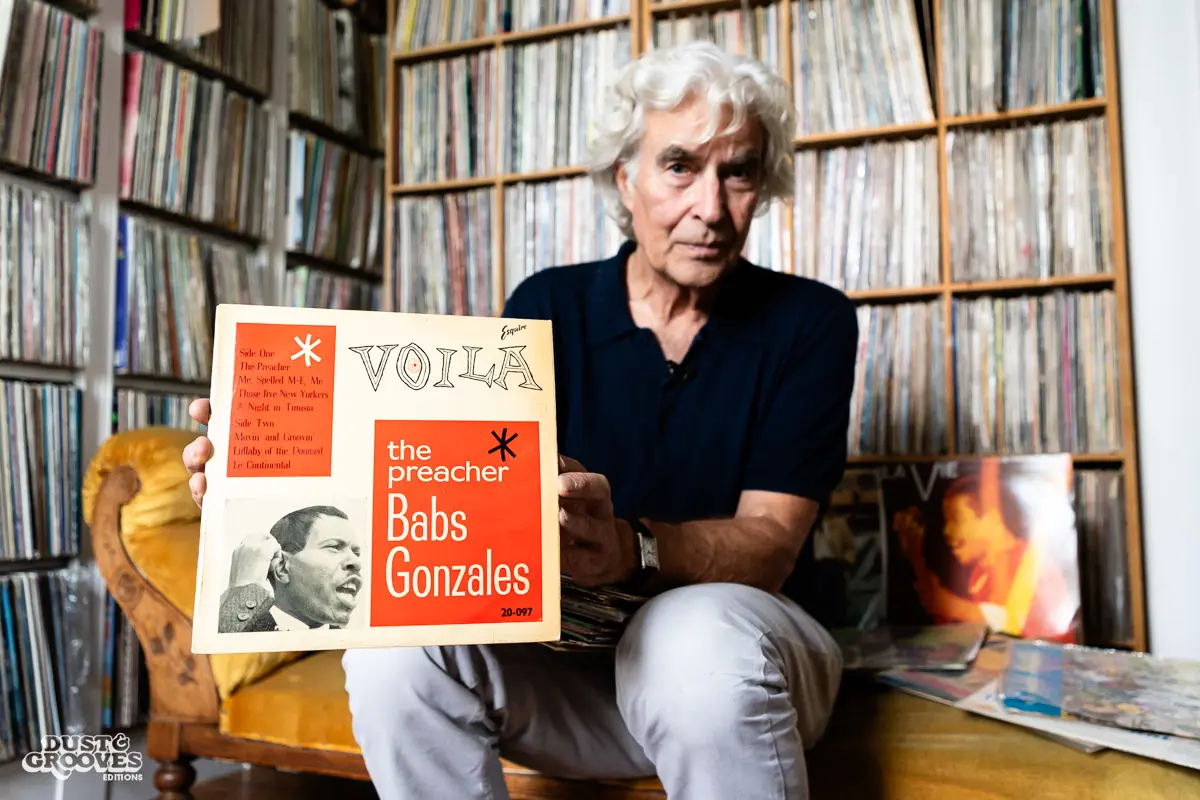

Babs Gonzales – Voila the Preacher. “While writing for the London-based 1980s magazine Black Music & Jazz Review, I became obsessed with jazz vocalists, especially after interviewing the amazing Betty Carter one night at Ronnie Scott’s club in Soho, London. Carter recommended Babs, so who was I to disagree? Babs Gonzales had it all—a kind of musical Jack Kerouac, with a touch of Slim ‘Vout-o-Renè’ Gaillard on the side. This is the original 1958 10-inch issue, his debut LP, I believe.”

Various Artists – Banda de Sonido Original de la Película Se Solicita Muchacha de Buena Presencia y Motorizado con Moto Propia. “This is an extraordinary movie soundtrack by Juan Carlos Nuñez—somewhere in the crosshairs between salsa, Afro-Latin jazz, and freestyle jazz. It’s a wonderful disc with a 24-piece orchestra.”

“In the mid-1980s … it would be a fusion of African rhythms, English lyrics and a sound that you could recognize and people loved it. I suppose we used to get sixty percent African and forty percent white English down there, and everyone reacted the same.”

John Armstrong Tweet

And working at clubs must have brought in a wide range of experiences?

Yes. The second game-changing experience was a big kickstart for my career—working at the club Bass Clef from 1984 to 1996. I was doing Latin music and African music mostly—African on Saturday nights and Latin on Fridays.

The third one for me was being in Paris, where the African music scene was very established. I went to a funny old club called Shabele Lomba—one of those places in Beje where women of a certain age were looking for good-looking young Black men. That’s what it was all about.

The music was amazing, and for the first time, I heard Congolese music being properly mixed with salsa. They’d been doing that for years—it was nothing new. But for me, it was wonderful to hear it for the first time. I was going to Paris once every couple of weeks to get new records from an amazing shop called Afrique Musique, and I always used to go to the club and listen to what this guy was playing.

One night, he said to me, “I have something you’d really want—but you’re not having it.” It was Kassav. I already knew Zouk la sé sèl médikaman nou ni, which introduced a completely new way of producing. It just blew me away. You could tell everyone was blown away—even the older African music heads were stunned by this new sound. That really made me want to get into playing Congolese music.

When I was at the Bass Clef, I played new music coming from the continent. I loved all the old music, but I wasn’t going to play Fela Kuti—I loved him, but everybody else was playing him. I felt there was other music out there that needed attention. For me, the true magic has always been in Congolese music—if you really want to know, I just love the melodies.

This vinyl, M’pompon Kuleta by De L’Afrisa International from 1981–1982, was important back in the day and is now actually on an Afro-rare groove compilation I’m doing with BBE. Whether or not it’s rare, I don’t care—it’s obscure. I’m playing it for you because, to me, it shows the depths of Congolese music. Here’s a guy hardly known at all, and the record is just perfect. What I love about the production is the arrangement—it’s very careful, almost like a classical piece.

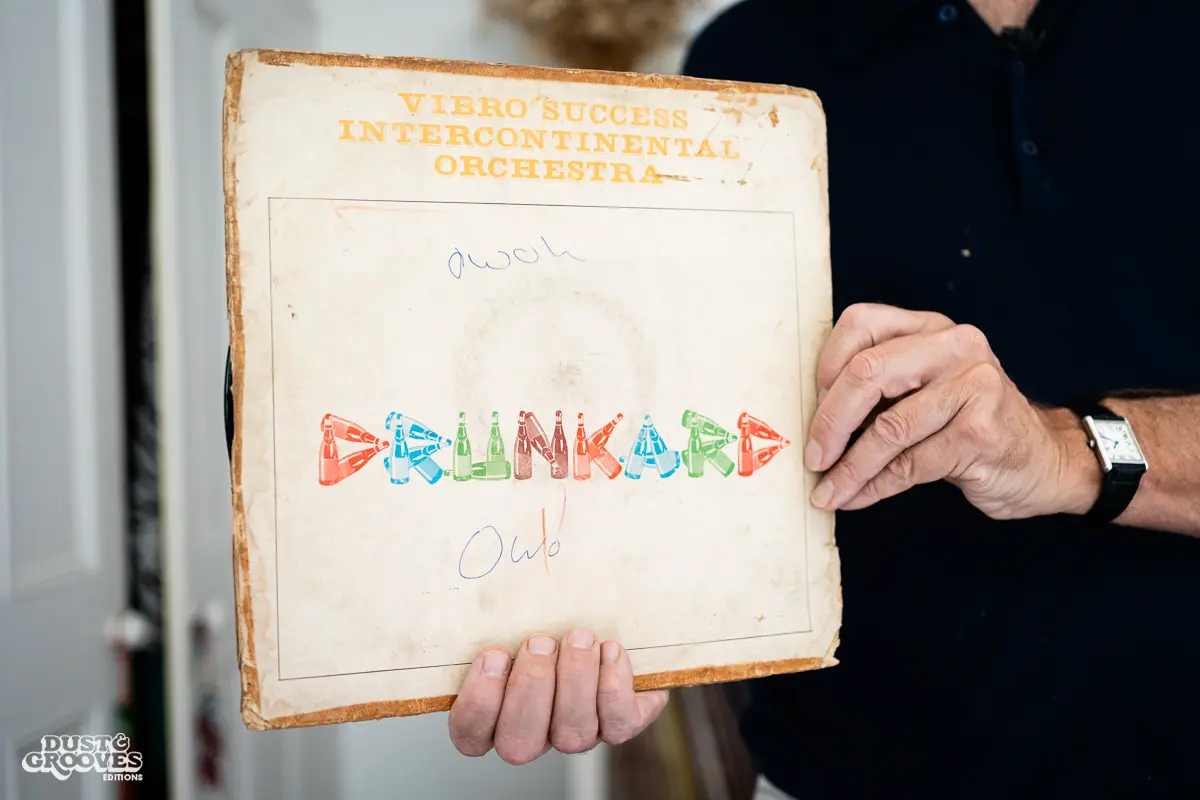

Vibro Success International Orchestra – Drunkard. “This is an original copy—it’s now been reissued, but my original seems to sound deeper. Long disbanded, Vibro Success was a mix of Central African Baya and Banda musicians, plus a few Congolese players—all recorded in Nigeria. Drunkard is one of those impossible-to-categorize tunes: is it afrobeat? Is it psych rock? Soukous?”

La Retreta Mayor – Self-titled. “Most of us know how great Cuban, Puerto Rican, Colombian, and North American Afro-Latin dance music is, but Venezuela often seems to drop off most people’s lists—monstrously unfairly, because Venezuela is bursting with talent. I’ve chosen this brilliant Latin funk obscurity by La Retreta Mayor. The Crusaders meet Irakere. It’s the only copy I’ve ever seen.”

You started DJing in iconic clubs like the Belsize Park Town & Country Club and Whisky a-Go-Go. During the 1970s, those venues were mostly geared toward prog rock audiences. DJing Brazilian and African records for a crowd that had never heard that kind of music before must’ve been an interesting experience. What was that like?

Yeah, it was briefly Whisky a-Go-Go. This was in the late 1970s to early 1980s. There were people like Chris Sullivan. The whole post-punk scene—a lot of these makeup artists and scene makers—was about dressing up.

I was playing them wherever I could. There was Whisky A-Go-Go, which wasn’t doing very well. I don’t know why. I was doing this night with a woman who was a writer for The Face magazine. We called it The Hotbox. I used to play a mixture of Northern soul and soca, and for some reason, it worked. I used to do a night called Roots with Zoots, which was 1940s and 1950s jump-jive, Black rock’n’roll. Once you got people warmed up, you could stick on a highlife record or a soca record.

Anyway, we only did it for two or three months, but there were all kinds of weird things like that going on. Then there was a club called the Beat Route, again one of those old discos on Greek Street. There were two guys—Steve Mahony and Oli, who was a hairdresser. They wanted a place to play records to their friends, so they made a deal with this club. They said, “We’ll charge money on the door and split it with you. We’ll bring in the beer and split the profits from that.” And there would be queues around the block.

There was a DJ called Steve Lewis—he’s still around, but he doesn’t DJ anymore. He was playing all this kind of Talking Heads and post-punk stuff. He’d stick in a Fela Kuti or a highlife tune or something like that.

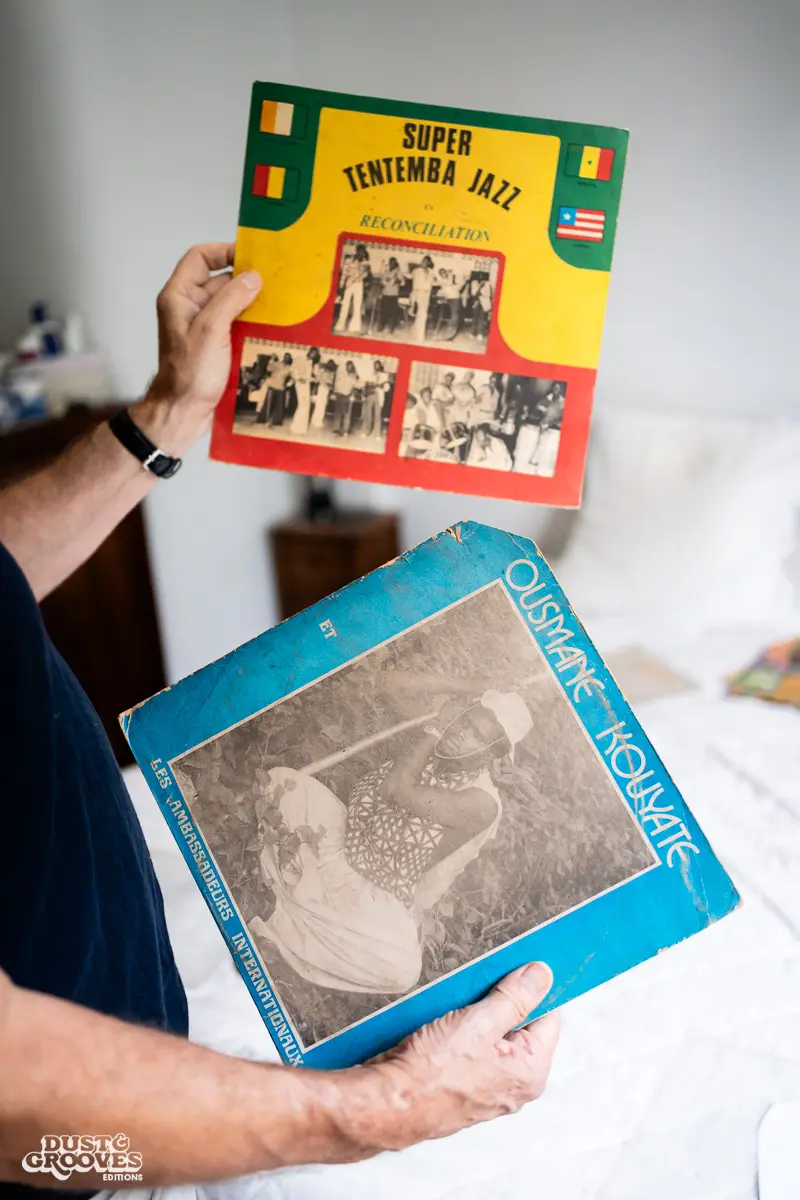

Ousmane Kouyate – Kefimba

Super Tentemba Jazz – Reconciliation

“A couple of my current West African vintage Sahel-style dancefloor fillers: Ousmane Kouyate’s Kefimba (1980), from Abidjan’s long-defunct Musiques Mondiales (everything on that label is highly recommended). And Mamadi Diabate’s Super Tentemba Jazz, an early co-production of the late, great Afro-music entrepreneur Ibrahima Sylla.”

What was the crowd’s reaction?

It was very difficult. You had to kind of seduce them. When I first started, I had all these really great zouk albums I’d just brought back from Paris. I played them one after the other, and everyone was like, “We want something different, please.” It wasn’t a smooth transition.

We always had a live band as well—there were quite a few new African bands around. A lot of Sierra Leoneans had come over in the early ’80s, and quite a few Nigerian musicians too. They were doing their own thing. Music in the mid-1980s in this country wasn’t seen as a big intellectual thing. People just loved music, and there was this fusion—African rhythms, English lyrics, and a sound you could recognize. People loved it. I suppose it was about sixty percent African and forty percent white English down there, and everyone reacted the same way.

At the very beginning of this scene—if you go way back—there was already a mixed crowd in England in the 1950s rock’n’roll vinyl scene. And even earlier, in the underground club scene in Soho in the ’40s and ’50s. It was mostly jazz, but a really weird mix—African-Caribbean immigrants, Ghanaians and Nigerians playing highlife, and the crowd would stay drinking until three or four in the morning. It was the only place you could do that in the country.

And they were the only people who could really afford to go out at that time, because it was just after the war. So you’d get aristocrats down there—Princess Margaret, jiving away to calypso! There’s been a Black music scene in this country for a very long time. There was a guy called Leslie “Hutch” Hutchinson—he was a great idol of my mother’s. He was the first African artist to really succeed in England. A proper idol in aristocratic circles in the 1920s and ’30s. He had a European sound—not at all an African sound.

Was there a specific record you remember when you were DJing that was outstanding?

I used to play this album Aluana Nwu Elie Na Ndo by Goddy Ezike & The Black Brothers. His family comes from the Cross River State in southeast Nigeria, where the music is very highlife-y, and you could hear the Congolese influence. Serotonin guitar lines that I love—there’s also a bit of gospel.

Goddy Ezeke – Alua Na Anwu Elie Na Ndo. “Goddy Ezeke is a wonderful Igbo (southeast Nigerian) gospel singer and songwriter. I fell in love anew with Igbo music when I curated the Igbo Tabansi record label reissue for BBE Records a few years ago. The Igbo highlife sound is more guitar-based than Ghanaian highlife, so it is a great favorite with Colombia’s ‘picotero’ champeta sound system jocks.”

“There is a commodification of vinyl. It has become a commodity, and for a lot of people who made no money at the time, it is particularly ironic that it came around a second time and they still don’t get money out of it.”

John Armstrong Tweet

During my travels in Africa, I didn’t see any record shops. To some extent, the vinyl scene is non-existent. In fact, these days, old African records are of great interest only to “Western” DJs and consumers. How do you feel about the fact that most of the countries from which much of your music is drawn do not use or play vinyl and may not even have pressing factories?

So what you’re really talking about is exploitation, which is wrong. I think it’s very wrong. There are a lot of labels that are doing that. There is a commodification of vinyl. It has become a commodity, and for a lot of people who made no money at the time, it is particularly ironic that it came around a second time and they still don’t get money out of it.

I don’t want to criticize or bring into the spotlight any record company in particular—but several do. But I mean, this has always happened with African musicians. It’s not just Europeans—African people are always ripping each other off. I can think of one very famous record producer who used to bootleg his own records. He sold his records in Paris, Europe, and so forth. He’d give them licenses and bootleg them and sell them in Africa. So it has always happened, and it’s not specifically a European thing. It’s wrong, but it’s not only European. Also in America, it happens all the time.

As an editor who has published compilations both on vinyl and CD, what do you think is the difference between these two mediums from the consumer’s perspective? Was it hard for you to transition to CDs? How do you feel about the fact that vinyl is now relevant again?

I think it’s great. I’ve always had vinyl and CDs—I’ve never been in one camp or the other. I’m not a professional sound technician. To me, a well-recorded CD sounds pretty much the same as a well-recorded LP.

But the lovely thing about an LP is what it says about the artist. You pick it up and there’s a beautiful picture, and you start thinking, “What is he doing there?”—about the musicians. You can hold it, which you can’t do so much with a CD.

What I hate about CDs is the plastic cases. They break, they come apart, and you lose the record.

Alfredo de la Fe y su Afro Charanga – Para Africa Con Amor. “A pan-Latino LP made in heaven—in this case, a full charanga orchestra. Leading Cuban jazz violinist Alfredo de la Fe, top session singers Felo Barrio (Cuba), Jose Alberto (Santo Domingo), flute Dick ‘Taco’ Mesa, piano Sonny Bravo and Alfredo Rodriguez, percussion Nicky Marrero, and guest vocalist (from Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire) Doh Albert. Nothing left to chance—and it shows. A perfect LP.”

Over the years you’ve been DJing, the platforms for discovering music have shifted—from radio shows, record shops, and club DJs to MTV, YouTube, and now social media. How do you feel about those changes?

I think it’s a bit odd. Let’s say you’re a record promoter in 1952 and YouTube suddenly comes into existence. Would you use it? Of course you would. Like it or not, I don’t think it’s a mystery that people put out their music that way. I think it’s a terrible injustice for the musicians who are making the music, that they get their music on Spotify. What do they get, £0.001 per play? This is the unacceptable face of market forces, isn’t it? If you don’t like it, you have to find another way to reach that audience. But not everyone can do it. They have to go on with what’s available.

Back when I was a kid, the way I used to listen to music was on the radio. I mean, the first times I heard my heroes like Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran, Elvis Presley. There was a show called The Saturday Club from 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. on Saturday mornings, and I listened religiously to that because it was the only place you could hear it. You couldn’t hear it on TV—well, if you could get Radio Luxembourg, you could, which was on 208 FM, but it had a very dodgy reception. I used to listen to it under my sheets when I was supposed to be sleeping.

How do you get to new music nowadays? Is it through Youtube, Bandcamp?

Sometimes I look through YouTube, and I usually look for music from places I haven’t checked for a while. Let’s say Equatorial Guinea—just type it into YouTube and you’ll find music that has only 27 views. I’ll go not just to the music sites but also the main sites. It’s interesting to get insight into what the industry is like and also the current cultural psychology. What is the predisposition of people in Lagos right now? What music do they like? What films are they watching? I think it’s all really interesting.

Ary Lobo – Ultimo Pau de Arara. “Another great 10-inch. Brazilian nordestino pioneer Ary Lobo—more baião e canção—i.e. slower tempo, more melancholy—than Jackson, but just as beautiful.”

As a DJ and compilation editor, what’s your take on the rise of collaborations between young producers in Europe with African artists?

Some of the music coming out on Soundway, or like Ibibio Sound and all of those people, it’s great, I love it. I find that if you play African modern popular music, I think a lot of British people think it sounds a bit cheesy but I think it’s because it’s very aspirational. A Lot of African music, especially Zimbabwean music, has a very aspirational feel, and I think that sometimes from a cynical, skeptical Eurocentric point of view, it sounds cheesy when it’s not cheesy. I think that these new collaborations avoid that and so they play to a European audience in a way that is not Afro-cheesy.

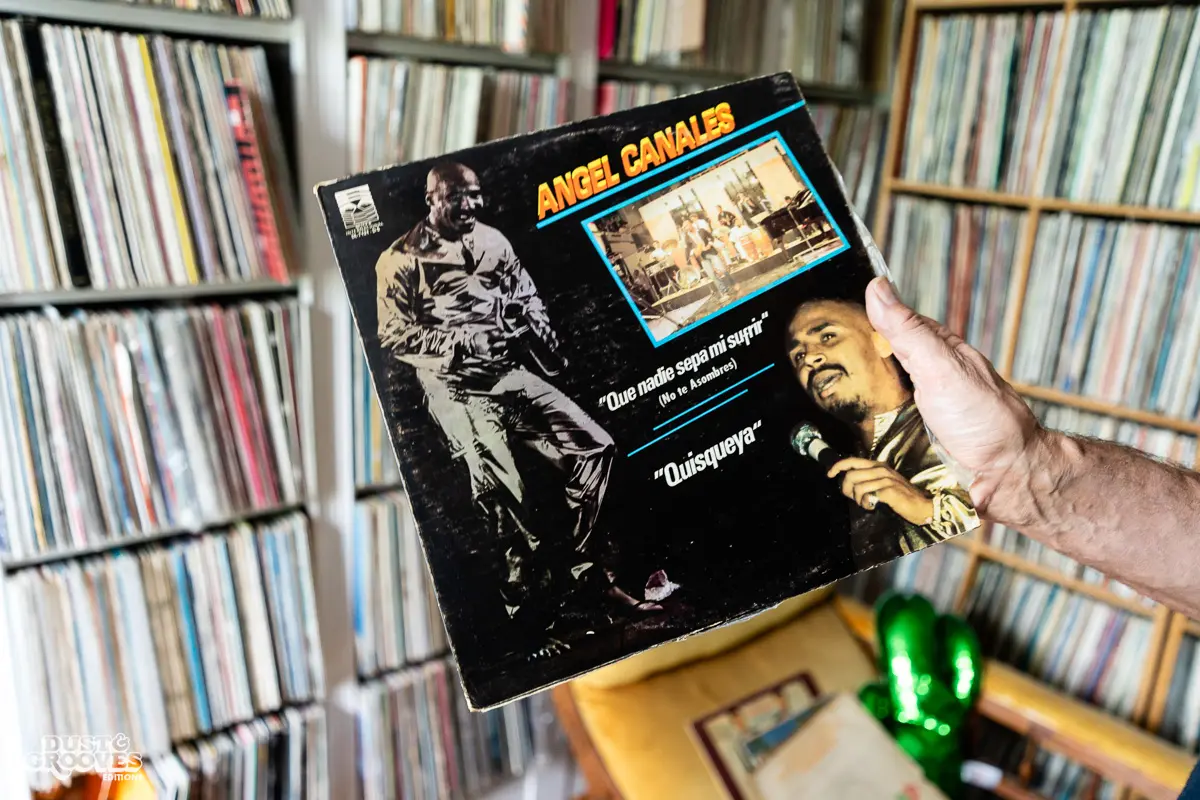

Angel Canales – Que Nadie Sepa Mi Sufrir. “Angel Canales is a fascinating Brooklyn-based Puerto Rican vocalist with very little output over the years—no more than half a dozen albums. This one is a rarely seen, Venezuela-only live concert LP. His style is very different from the usual Cuban-type sonero—he has a slight sense of menace in his voice. There was a rumor that he gave it all up to become a Brooklyn municipal trash collector. But those rumors seem to be just that. He’s just released a new album in the currently fashionable bachata style. His records remind me also of a dear departed friend, UK-Polish salsa DJ Tomek, who was also a big Canales fan.”

What are your thoughts on fair compensation for artists across different mediums—vinyl, CDs, and streaming?

I was working on intellectual property litigation—like, I wouldn’t say their name, because they are really famous. But it was a very interesting period, I remember. When record companies had tied a lot of famous people into contracts of getting paid their royalties by reference to the price of a vinyl record.

So let’s say vinyl records were £5.99, and suddenly CDs came along and they’re £10.99, but the record companies managed to say, “Well, we’re only going to pay a percentage of £5.99, not £10.99.”

The first person to bring a case was Paul Simon, in the States, and he brought a case against Columbia. I brought a case on behalf of someone whose name I can’t mention—his name equally as big as Paul Simon—and we managed to get them to pay. At first, they said no, but we managed to get them to pay money based on the £10.99 royalty. And now it’s all gone the other way, you see. Right now CDs are really cheap—CDs are like five, six quid; vinyl is twenty quid. I’m waiting for the same thing to start happening now. It’ll be quite interesting to see.

Tell us what you’re up to currently.

Now I DJ and it’s mostly a lot of the new stuff. I usually play on CDs, but I play on vinyl as well—it depends. A lot of the Cape Verdean modern dance, Américo Braga from Guinea-Bissau. A lot of the new Zimbabwean pop is incredible. I DJ’d in a gig before Mokoomba. That gave the opportunity to play a lot of modern Zimbabwean music to the Zimbabwean audience to see their reaction. They look up and they see a white guy playing their music.

Sometimes I want to stop doing compilations, but I always come back to it. This is my main passion. I like culture, music, movies, and food. I was never really interested in things that men were supposed to be interested in like football and fast cars. I suppose it’s the family I grew up in.

Who would you like to see profiled next on Dust & Grooves?

I think you should profile Peter Adarkwah, the proprietor of BBE Records. He’s done just about as much as anyone I can think of in the UK to enrich and modernize the whole vinyl scene.

John Armstrong is one of the UK’s most prolific and wide-ranging music compilers, DJs, and vinyl obsessives. A veteran of London’s DJ scene since the late ’70s, he’s championed sounds from across the tropics—Afro, zouk, salsa, Brazilian beats, and more—long before they entered the mainstream. With over 200 compilations to his name for labels like BBE and Sony, John continues to unearth and celebrate global grooves while also working on a major book project on African record cover art.

Further Adventures in Record Collecting

Dust & Grooves Vol. 2

John Armstrong and 150 other collectors are featured in the book Dust & Grooves Vol 2: Further Adventures in Record Collecting.

Become a member or make a donation

Support Dust & Grooves

Dear Dust & Groovers,

For over a decade, we’ve been dedicated to bringing you the stories, collections, and passion of vinyl record collectors from around the world. We’ve built a community that celebrates the art of record collecting and the love of music. We rely on the support of our readers and fellow music lovers like YOU!

If you enjoy our content and believe in our mission, please consider becoming a paid member or make a one time donation. Your support helps us continue to share these stories and preserve the culture we all cherish.

Thank you for being part of this incredible journey.

Groove on,

Eilon Paz and the Dust & Grooves team

3 Comments

DJ Jonathan E.

John Armstrong has long been one of my very favourite compilers. I have bought more than a few CDs unheard just because his name was on them. Urgent Jumping is particularly great - and full of music you won’t hear many other places. He would have been a major influence on me back in the day if I had known of him at the time. This was a fascinating read. Thank you.

Jörg Radloff

Great Interview!!!! Please Jello Biafra or Clint Eastwood next.

Eilon

Bring us to them, and we'll interview them :)