If you spot Alexandre Kassin in Rio de Janeiro’s Botafogo neighborhood, you’d be forgiven for thinking he might work at a tech startup around the corner. There is little about his demeanor or outward appearance to indicate that he is one of the most prolific and accomplished musicians, composers, producers, and arrangers in the contemporary Brazilian music scene. Despite his impressive body of work, filled with legendary names like Caetano, Elza, and Jorge Ben, Kassin prefers to stay far from the limelight. The reason why? If you ask him, he’ll tell you he’s worked hard to keep it that way.

While Kassin prefers the behind-the-scenes lifestyle, nearly everyone in the music world admires him. One of the last times I saw him was when he was DJing for Adrian Younge at a Jazz Is Dead pop-up event in Rio. Marcos Valle and João Donato [who has since passed] are Kassin’s personal friends, as is Gilles Peterson, who called him to work on his Sonzeira project. The late great Gal Costa used to regularly message him just to say hello and ask how his family was doing.

Speaking with Kassin, one can realize this love and admiration may not have been so abundant in his early years. His difficult family situation forced him to grow up at a young age. Music became a salvation; his record collection was his sanctuary. It was a privilege to sit down with him, first in his home and then in his studio, and hear stories about a life spent in music.

"My first memories in life were spinning records all day long. As a child, I remember just listening to records, records, records all the time."

Kassin Tweet

Could you introduce yourself and share a bit about your background?

My name is Kassin. I’m a musician and record producer from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. I started playing when I was eight years old. My brother was a DJ in the late ‘70s which, at the time, was called a discotecário, before the term “DJ” had arrived. My first memories in life were spinning records all day long. As a child, I remember just listening to records, records, records all the time. My brother was DJing at night, so sometimes I would go and see crazy stuff. Even as a child, they would allow me to go into the DJ booth with him, and I’d see people sniffing cocaine or hooking up or whatever [laughs].

I have these memories of going to discos with him. He was ten years older than me but wasn’t that old either. He was fifteen or sixteen, and I was around six, going to clubs like Papagaio. He worked at Papagaio Disco Club and Roxy Roller, a roller disco. He was a DJ in all the known disco spots in Rio. So that was the first thing that got me into music—the records that my brother showed me.

Then I started playing guitar a bit. My points of reference for playing were my records. I had this ritual where I would put a record on and try to play all the parts; it was my kind of fun as a kid. I am not thinking in the sense of being an instrumentalist, but I am choosing to think about the record’s arrangement, how it fits together, and how it works. That’s pretty much what I still do to this day.

So when you listen to a record, you’re not a passive listener. You’re always paying attention to the arrangement, the different parts, and how it all fits together.

Of course, I’m still taken by music. When something starts playing, if it’s a great song, I will be moved by it. But that part of the finesse of the recording is always somewhere in my mind. Sometimes, that’s what makes me emotional. It touches me when something is well crafted in terms of arrangement or production. Sometimes, I will listen to a song that is so well done in terms of its arrangement or recording that I feel like, “Oh, fuck!” And that gets me more than the song itself…

Just the attention to detail, the craft…

Yes, if a song is well crafted, it will take me somewhere.

Can you tell me the story of learning to play outside of playing along with records?

Yeah, when I was ten years old, more or less, my neighbors from the apartment below were Edson and Tita Lobo. To this day, they are good friends. I owe them all my music skills. They were the ones that put me on this path properly. I came from a difficult background. I was already working by the time I was twelve. They put me to work in music and started teaching me.

I also started going to a church choir. I didn’t have money to buy instruments, so I would study in Edson’s house while he was teaching me. The other option was to go to the church to play. The maestro of the choir was Domingos, and he was a good friend of Elcio Cáfaro. So, in my earliest memories of playing, Cáfaro was always around. He’s a great musician; I love his playing. We’ve played together a few times. It’s always good. He’s still doing great things; he’s a great drummer and person.

"I love the feeling of buying records you don't know; sometimes, the best find is music you weren’t aware of. That's always been the point for me.”

Kassin Tweet

When you started collecting records, I imagine some of your first records came from your brother.

Yeah, that’s the funny part. Since I was a child, my brother would play me the records, but he would never let me touch them because he was afraid I’d scratch them. So, I started saving money to buy my own, and, little by little, I began to have some records of my own.

Do you remember one of the first records you bought that you still have?

Kraftwerk! Computer World.

Did you first hear that from your brother?

That was one of the first records I heard that made me feel like, “Whoa! That’s incredible!”

It’s amazing the influence Kraftwerk had on music around the globe.

This is something that is really hard to create, you know? When I listen to a record, I play it thinking, “Oh, this is probably like ‘83,” or whatever. I can put a date on it immediately. But with Kraftwerk and João Gilberto, it’s hard to date it.

You mentioned having a tough childhood and working from a young age to save money to buy your first record. When were you able to really begin collecting seriously?

I don’t think I ever became a serious collector [laughs].

Ok, fair enough. Let me rephrase that. At what point did you realize you had a nice record collection?

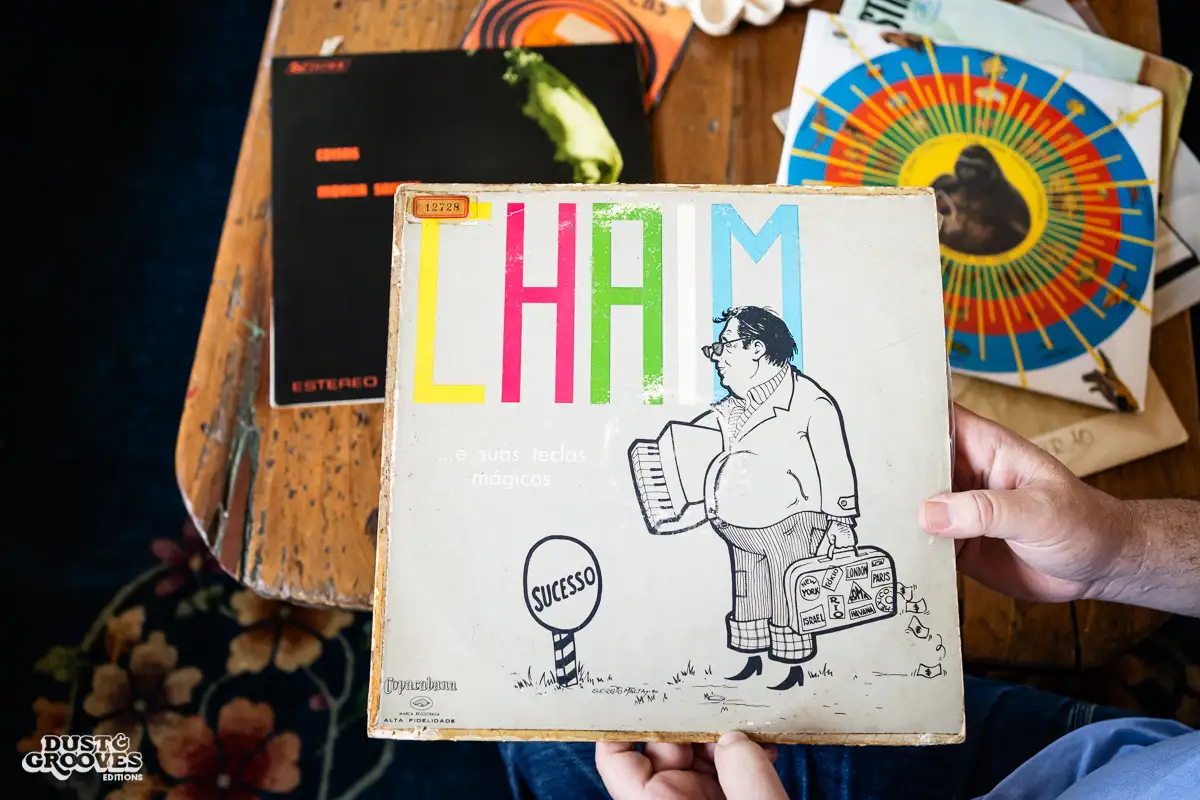

When I was 19, I was hired by Globo [a Brazilian media conglomerate] to be a music producer. I kept buying records to learn music. In the 90s, when you could buy records for R$1 [about twenty US cents], I often left with fifty records, which is impossible nowadays. This led me to buy unfamiliar artists and genres.

I love the feeling of buying records you don’t know; sometimes, the best find is what you weren’t aware of. That’s always been the point for me. This is still what I love to do—find records that I am not aware of. Of course, there are also records that I know and am looking for. Of course, sometimes I buy them as well, but I’m not the type to pay R$100 for a record.

I realized I had a big collection when I noticed that my LP collection was bigger than my CD collection. Because when I worked at Globo, I’d receive a big bag of CDs every week from all the record labels to choose the music for TV programs.

“Gary was the one who rediscovered Pedro Santos. He came in one day like, ‘Oh, I bought this record with a monkey on it.’ He put it on, and we were like, ‘Oh, fuck! This is great!’”

Kassin Tweet

So, when you worked for Globo, your job was to compose music for TV and find other music for them to use on different programs? Like a music supervisor?

Back in 1993 or 1994, they would hire you on a salary, and you would work wherever they would send you. One day, your job would be to record a live band; the next day, you might be writing music for a novella or background for a TV program. So they would send me a lot of stuff, including CDs, every week. At a certain point, I realized it was odd that my LP collection was still bigger, even with all the CDs I had received.

“Another thing I always pay attention to is whether Luiz Simas from Módulo 1000 is involved because he was the first guy in Brazil with synthesizers. If I see any record from the ‘70s with his name, I know it will have a crazy synthesizer sound.”

Kassin Tweet

Did you have anyone who taught you key things to look for? Labels to pay attention to? Or did you always just go by your own ear?

I’ve always collected records that match my taste. I never really cared about labels. Sometimes, I’d buy a record because I’d see a friend had played on it, or if I saw that a certain person was involved, I’d know that something good should be happening.

I think Gary Corben also helped me. In the mid-90s, we were flatmates, and he was showing me a lot of music from London, and I was showing him some things. We had an exchange going on because we shared a similar taste. Also, my friend from school, João Duprat, with whom I had the radio program on Worldwide FM. He’s a big collector as well. So there was always this exchange. Ed Motta was our friend since we were 16 or 17. These were the people in our little group, constantly exchanging information with each other.

For example, Gary was the one who rediscovered Pedro Santos. He came in one day like, “Oh, I bought this record with a monkey on it” [laughs]. He put it on, and we were like, “Oh, fuck! This is great!” Then we digitized it and started to share it like, “Check this out! This is great!” and the thing got more prominent.

You mentioned that you’d buy a record if you saw that a friend had played on it or that if you noticed a specific name, you’d know it would likely be good. When you find a record you’re unfamiliar with, which names would get your attention if you spotted them in the album’s credits?

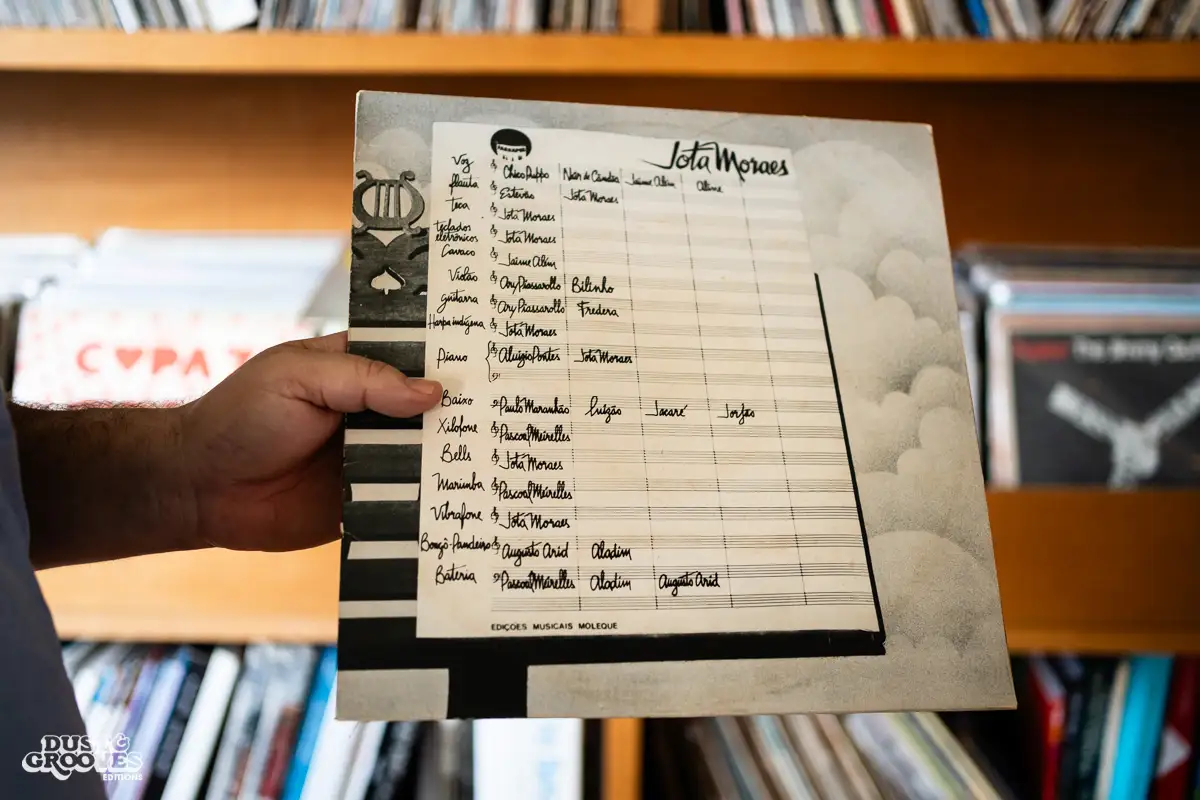

If I see any records with the pianist Luiz Eça on them, I immediately buy them. Or Hélcio Milito and the members of the Tamba Trio because I think they are masters of their craft. Another thing I always pay attention to is whether Luiz Simas from Módulo 1000 is involved because he was the first guy in Brazil with synthesizers. If I see any record from the ‘70s with his name, I know there will be a crazy synthesizer sound. The Azymuth guys, for sure. Pedro Santos and Joel Nascimento are other great names.

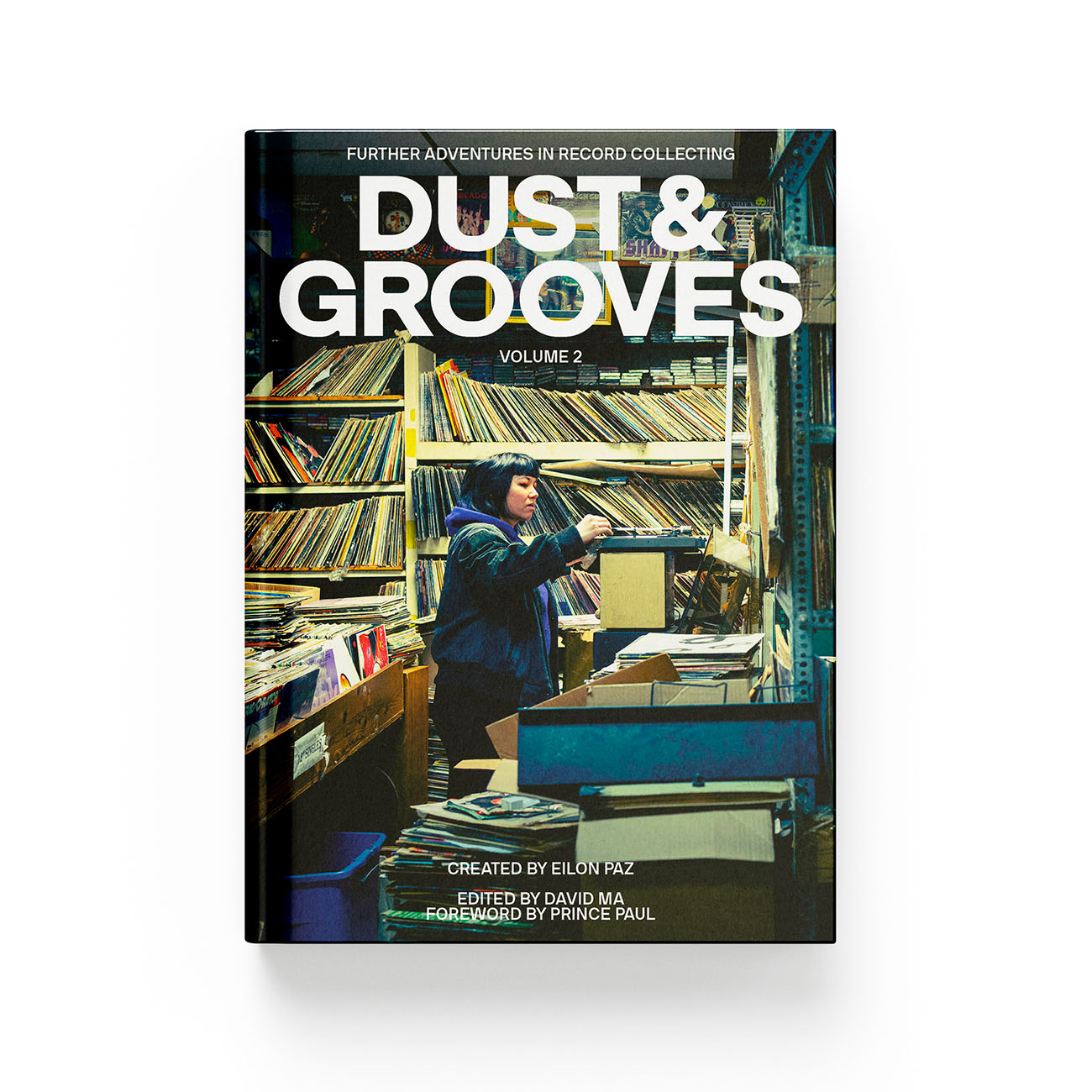

Further Adventures in Record Collecting

Dust & Grooves Vol. 2

Kassin and 150 other collectors are featured in the book Dust & Grooves Vol 2: Further Adventures in Record Collecting.

You touched on the idea that certain records were like a school for you as a musician. What is a record from your collection that comes to mind that helped you to understand arranging?

It was one of the first records I bought, maybe the third. After Kraftwerk, I bought Marvin Gaye and Lincoln Olivetti and Robson Jorge. That album spoke to me since the beginning; it had details and arrangements that I really paid attention to.

What are some of your favorite records in your collection that Lincoln Olivetti was involved with?

Mariana’s record on the 3M label from 1987, De Ponta A Ponta. I think the track “A Música Não Pode Parar” is one of his best. And the “Directory” record! [It’s Lincoln and Robson under a different alias].

The Jon Lucien compacto with “Come With Me To Rio” is another good one. I don’t know much about that story, but I know Guto Graça Mello [former music director for the Som Livre label] met Lucien, and he came to spend a holiday in Brazil. He made that incredible tune with Guilherme Arantes with Maria Bethânia singing on it, “Brincar De Viver” from Plunct Plact Zuuum ]. Around this time, strange songwriting partnerships were developing, like those between Leon Ware and Marcos Valle. I love these “bridges” that were happening around this time.

Did that all start with Sergio Mendes?

I don’t know. I mean, it started with Sergio, for sure. But there was also this parallel boogie thing in the ‘80s, like the Simone record with “Tô Que Tô.”

Going back to Olivetti… rumors were floating around for years about a tape that was discovered from an unfinished project that was a follow-up to Lincoln Olivetti and Robson Jorge’s LP from 1982. It’s out now, a five-track EP, Déjà Vu. Who discovered these tapes?

Lincoln’s daughter, Mary Lin. She found some tape that appeared to be the Rio Babilônia master tape, and she asked me if I could transcribe it so we could have the multi-tracks. The tapes were in horrible condition. We needed to bake them and do it right away because they were dying. So, I digitized the whole tape, and there were some original tracks that no one knew about.

We started listening and were like, “What was that?!” Some of them were finished. Like, the whole thing was there. And some of them sounded like demos. Lincoln and Robson were playing, but Lincoln was singing the horn parts he had in his head. We took the parts that we had and added the horns with his ideas. It was incredible to have the chance to do this. It was like these mixed emotions… I happened to be a dear friend of Lincoln, but Robson was an idol for me as well, and I never got to meet him. So, to be able to collaborate somehow… It was crazy, man.

"Tim Maia was the first time I had the chance to do something like this—to complete a project for someone posthumously."

Kassin Tweet

You’ve had the amazing opportunity to work on these lost Olivetti tapes, but it’s not the first time that a project like this has come to you. Incredibly, you were also presented with lost tapes from Tim Maia’s unfinished Racional Vol. 3. How did that come to be?

Tim Maia was the first time I had the chance to do something like this—to complete a project for someone posthumously.

A friend of mine, William Junior, is the son of the owner of Studio Haway and Somil. Somil was where the Verocai album was recorded and where Tim Maia recorded. Somil was like a studio to record advertisements and jingles; he found this tape in a trash can. William had worked with Tim Maia; he was doing PA for Tim Maia’s live shows in the ‘80s, and they were friends.

So, this tape found in a trash can had “Tim Maia” written on it, so William asked, “Hey Dad, what’s this?” His dad was like, “Oh, that fuck Tim Maia never paid me!” William digitized the tapes, thinking they sounded like something from Racional. So, he called me like, “Hey, I think I found some tapes from Tim Maia Racional, but I don’t know these songs. Can you check for me?” He could hear Tim singing about this “rational culture” and thought he’d maybe found the master tapes from a Tim Maia Racional record. However, he didn’t have Maia’s records to compare them to the tapes.

When I eventually listened to it, I was like, “An unreleased record! Oh fuck!” But I also thought maybe these were songs from one of the other Racional-era compactos, like the Tim Maia & Coral Nacional 7-inch. Before everything was online, these things were difficult to know if you didn’t actually have the record. So, I called my friend, João Duprat, who was working as a lawyer at BNDES, the big development bank, and I said to him, “João, check this out… you have the compacto, no? Is this from the compacto?” I held the phone up to the speakers and played some of it for him, and he was like, “I’M COMING TO YOUR HOUSE RIGHT NOW!” [laughs]

Twenty minutes later, he arrived at my house, still dressed in his suit, screaming, “WHAT WAS THAT?!” So, we put it on and realized this was an unreleased third album from Tim Maia’s Racional—period! From that point, a three-year-long process, elongated by politics and family, began to finish and release this record. I was talking to one lawyer for the family for almost eight months, and he didn’t want to talk to Carmelo about it until I had the whole finished album ready to show him.

Carmelo is Tim Maia’s son, right?

Yes, Tim Maia’s son. So, I started mixing the album; there were still some things we needed to finish. It was a struggle to make it happen. And, of course, this was a project I was not being paid to do. I was pushing it and pushing it without knowing if it would even come out.

Finally, I had some business with Nelson Motta, who was writing Tim Maia’s biography. At the end of our meeting, I told him I had something to play for him. I put it on, and he said, “I knew about this record, but we could never find it!” He then was able to contact Carmelo. He was vital to make this happen. Everyone involved with this project was someone who loved Tim Maia and wanted to make it happen.

Who did you bring in to record the unfinished parts?

I called Lincoln! I called everybody who had been working with Tim Maia at this time. I called Paulinho Guitarra, the man who played with him his whole life.

You completed a project for another Brazilian legend, Wilson das Neves. Tell me the story about that process.

Wilson had done the first recordings, but he started getting sick. So we hurried to get the whole thing moving. We set the date for the next recording session. He was going to start again on a Monday, and he died on that Saturday. Musicians were coming in from Minas Gerais [a neighboring state north of Rio de Janeiro]. Tickets were already booked and ready to record on that Monday, and he called me that Saturday saying, “I don’t think the recording is going to happen because we are going to the hospital.” I was like, “Yeah, we can delay this, no problem,” and he said, “No… I’m calling to tell you… I don’t think the recording… is going to happen,” he was calling to say goodbye.

He died that day, and the next day was his funeral. Everyone was there: everyone who was involved in the record, everyone he’d played with, and his fans. Sunday morning, the first person to call me was Emicida, and he said, “Hey, I know we’re going to record this. When you need my help, I’m there.” At the funeral, Chico Buarque came in like, “Hey, another record… we need to finish.” And I was like, “Yeah, of course. If everybody wants to make it happen, we can make this happen.”It wasn’t a big-budget thing, but we managed to do it properly. Senzala e Favela is the name of the album.

How did you connect with Shinichiro Watanabe on the Japanese animated series Michiko & Hatchin?

I performed some concerts in Japan, and at the end of the concerts, some people wanted to talk about a project. They turned out to be Watanabe and the show’s writers. I knew about Watanabe’s past work with Cowboy Bebop; I’d watched it before. And they started speaking like, “We want to do this animation. The music should be Brazilian and jazzy. We’d like you to do the soundtrack.”

It was a project that took a long time. From beginning to end, it was almost two years. I didn’t hear from them for eight months. And then suddenly, a huge box came in the mail. And it was all the scripts and all the ideas… how long each piece of music should be, what should happen, the BPMs, everything.

How many themes were there in total?

Sixty-four themes. Animation is different from movies, you know? They start to do the animation over the music. They wait for the scores and the dialogue. So there were some things that I had to deliver first. It was kind of divided into stages. And it was wonderful. I think it’s one of the works I’ve done that I’m the most proud of. Seeing it on the screen was incredible.

“Depending on the record, the Brazilian pressing can be so horrible that I often prefer a nice reissue made from a good master.”

Kassin Tweet

Many of the projects you tend to work on are heavily influenced by American funk, soul, and boogie. Those styles make up a large portion of your collection. What else are we likely to find on your shelves?

I have a lot of that, but I also have jazz and Brazilian records, of course. But I do not listen to one thing at a time. I get tired. One of the beautiful things about my job is that every day is slightly different. And sometimes, since I like to listen to music all day, I listen to things that are the opposite of what is happening in the studio. I’ll have periods where I listen to hardcore records or electronic music… I don’t have a specific theme. I love to listen to Debussy. I listen to a lot of classical music and jazz records.

What section of your record collection might surprise people?

There are a lot of Polish records. Polish and Japanese. Japanese because I was married to Hiromi [Konishi], and when we’d go there to visit, I started to buy a lot of Japanese records… city pop, jazz records, stuff on the Three Blind Mice label. I have Polish records because I made a record with a Polish band. I went over there all the time, and I started buying a lot of records there.

“I think of Nivaldo as the Brazilian Rudy Van Gelder.”

Kassin Tweet

Where do you prefer to get your records? Do you prefer a well-curated shop or…

No, no, no, no! I mean, I will go there… I like to visit these shops, and I have friends in these shops like Tropicalia. I’ll go there. I’m happy there because they also have a section that’s not pricey and is full of surprises. But I prefer places like the spot on Rua Siqueira Campos or Junior’s place downtown in that tall building on Praça Tiradentes. I prefer the messier spots where you can sit down and talk to the guys.

What about the sellers in Praça XV?

No, I never went there because I didn’t like the competition. That kind of place you need to go at 5 a.m. and nothing at 5 a.m. makes sense to me [laughs].

Let’s talk about reissues. How do you feel about reissues in your collection? I’m thinking specifically about Brazilian records here… is there a time when you might prefer a reissue to the original?

Depending on the record, the Brazilian pressing can be so horrible that I often prefer a nice reissue made from a good master. I have a few records here that I have both the original and the reissue, and the reissue sounds much better. Like Guilherme Coutinho.

Let’s get nerdy. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, who had the superior sound between EMI, RCA Victor, Philips, and Polydor records from Brazil?

I could talk about this the whole day! [laughs]

Any foreigner will always think that the most incredible Brazilian sound is on EMI. But two different phenomena are going on here. One is what Philips made in the ‘60s and ‘70s… there’s nothing like that in the world! Because they managed to take all the outsiders, the strange artists, and make it something really solid over the years. They had Jorge Ben, Caetano, Gil, Gal, Chico Buarque, Elis Regina. I don’t think Philips has the best sound quality, but they put together the most amazing crew. When you think about it, these are the main artists from Brazil.

What made those EMI records sound so incredible in terms of sonic quality? There are obviously a lot of variables involved.

It’s all about how it was recorded and mixed. I went to interview the engineer, Nivaldo Duarte because I had the same question. I was writing for this audio magazine, and I thought, Nivaldo is one of my idols; I will go and look for him. He told me how the whole studio was set up. It was really something else; the way they did everything was unique. For example, they had a big room with a high ceiling and built a vocal booth for the singers to sing in front of the musicians. They found putting the drums over the top of this isolation booth was best.

When you listen to the records thinking about it, the drums are not physically on the same level as the orchestra! They are coming from up high, and the way the cymbals and everything “leak” into the orchestra is so different. He taught me a lot of details about how they got that sound… a very, very, smart guy! If you listen to these records like Clube Da Esquina, they have an incredible sound. I think of Nivaldo as the Brazilian Rudy Van Gelder.

How was it working with Gilles Peterson on the Sonzeira project? You two seem like kindred spirits. I imagine a lot of the downtime was spent talking about records…

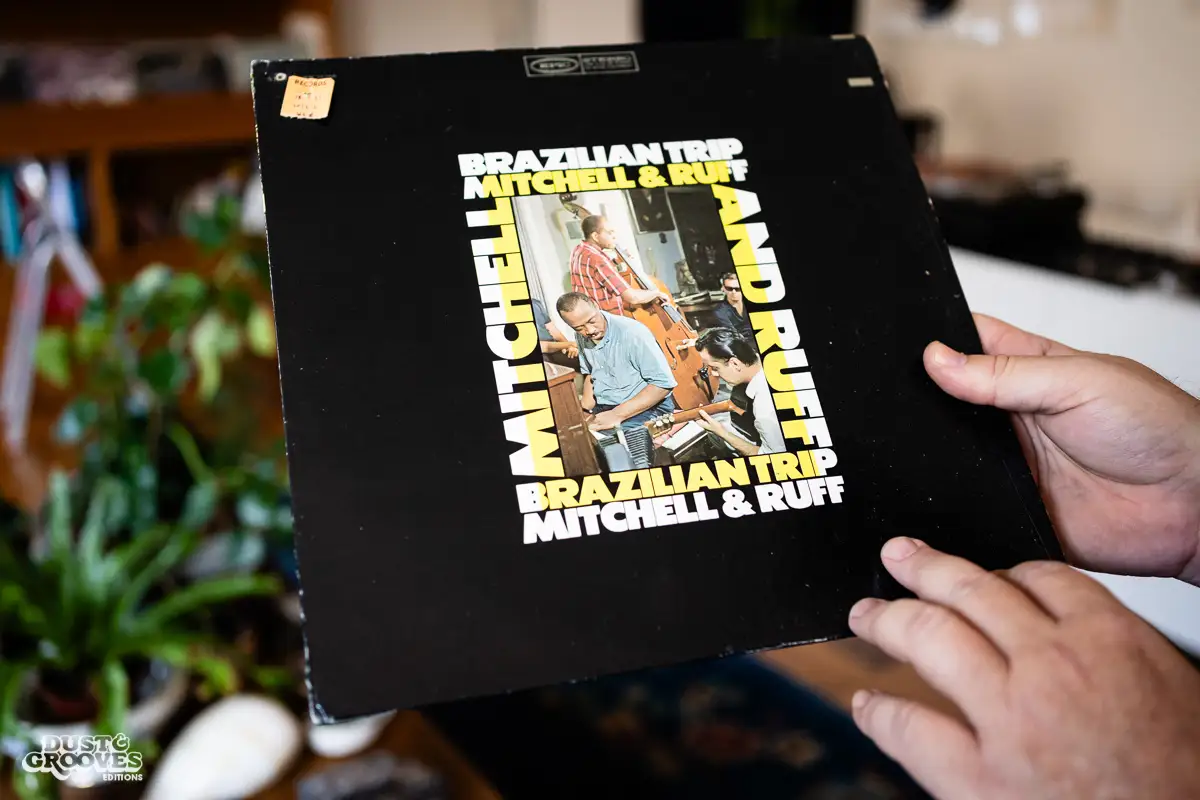

It was a wonderful time! I love him dearly. It was a record that I have a very fond memory of because it was so much fun being with him and listening to music all day. It was incredible. I think there’s a different perspective that British people have. You and I talked earlier about how Chuck Brown was massive in Brazil, but “Southern Freeze” [covered on the Sonzeira record] was massive in the UK, yet we had never heard of it here in Brazil! They were all like, “You’ve never heard this tune?!”

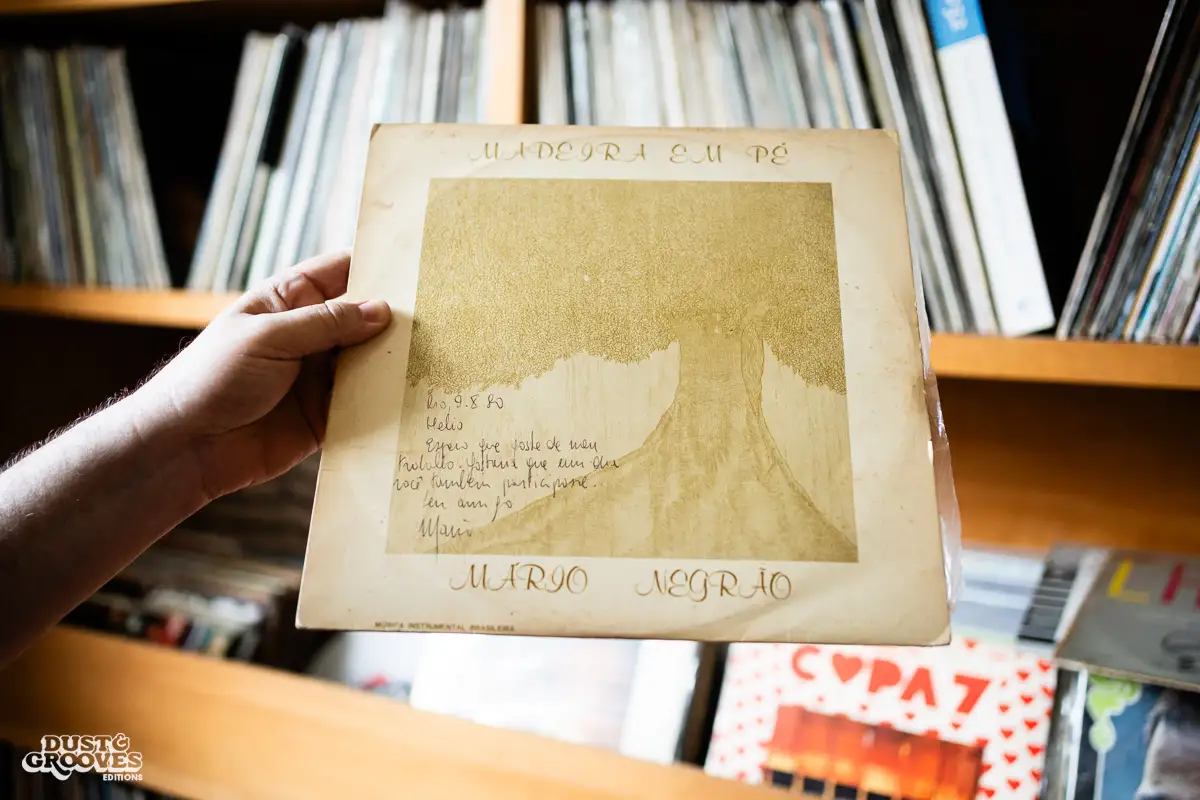

What are a few records that you could suggest from your collection that would change people’s opinion about ‘80s records from Brazil, particularly ones that came out after 1982, this arbitrary cut-off date for “good” music in Brazil that some people like to impose?

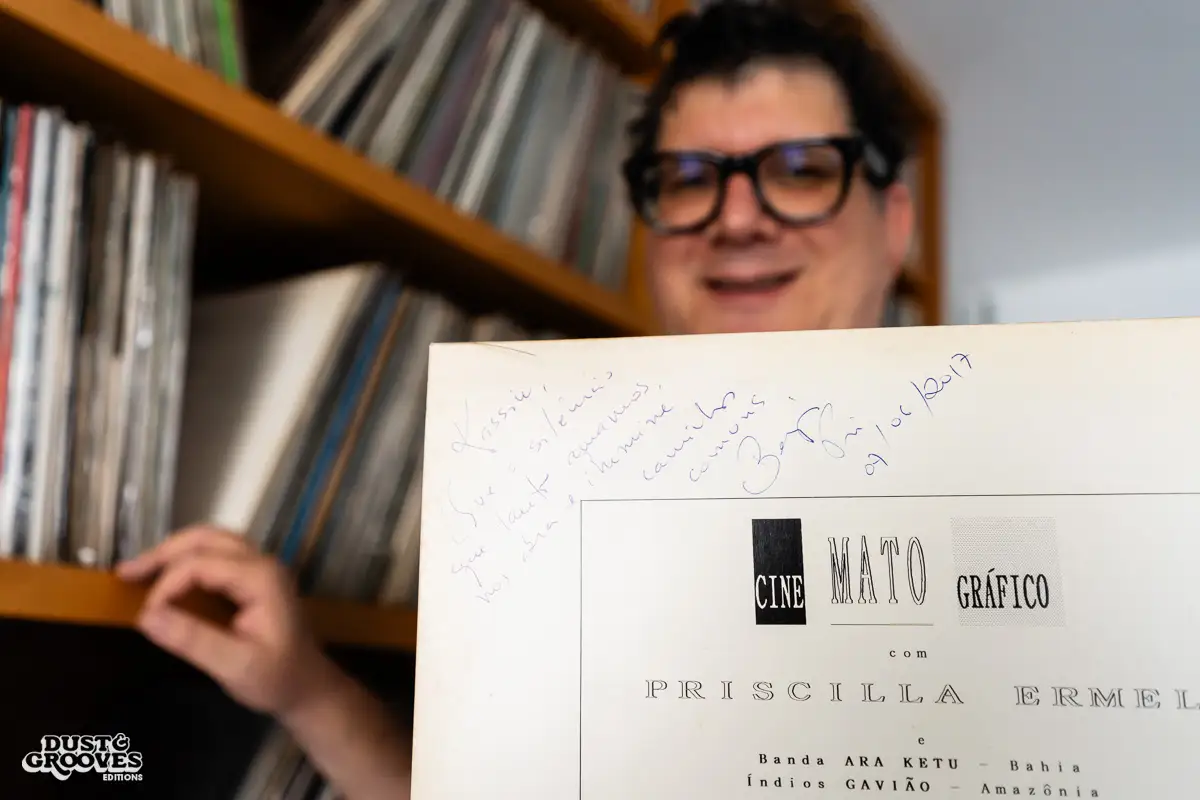

I think I already mentioned Madeira Em Pé from Mario Negrão. Records from the COOMUSA label, which is a great label. Another label that I think is incredible is Som Da Gente from São Paulo. Fredera, Costita…many, many, many good records on this label. And the guy who was the owner of that label was Walter Santos, the guy who came with João Gilberto from Bahia. I had the chance to meet him and become close friends with him; he told me a lot about the label. I would like to see a nice Som Da Gente project because I know they have a lot of unreleased stuff.

I think we all have one record that, to use a pharmaceutical metaphor, is like a sonic Prozac or Valium. Something we always come back to, that we know when we put it on, will set us at ease and our mood straight, no matter the kind of day we’ve been having. What is that record for you?

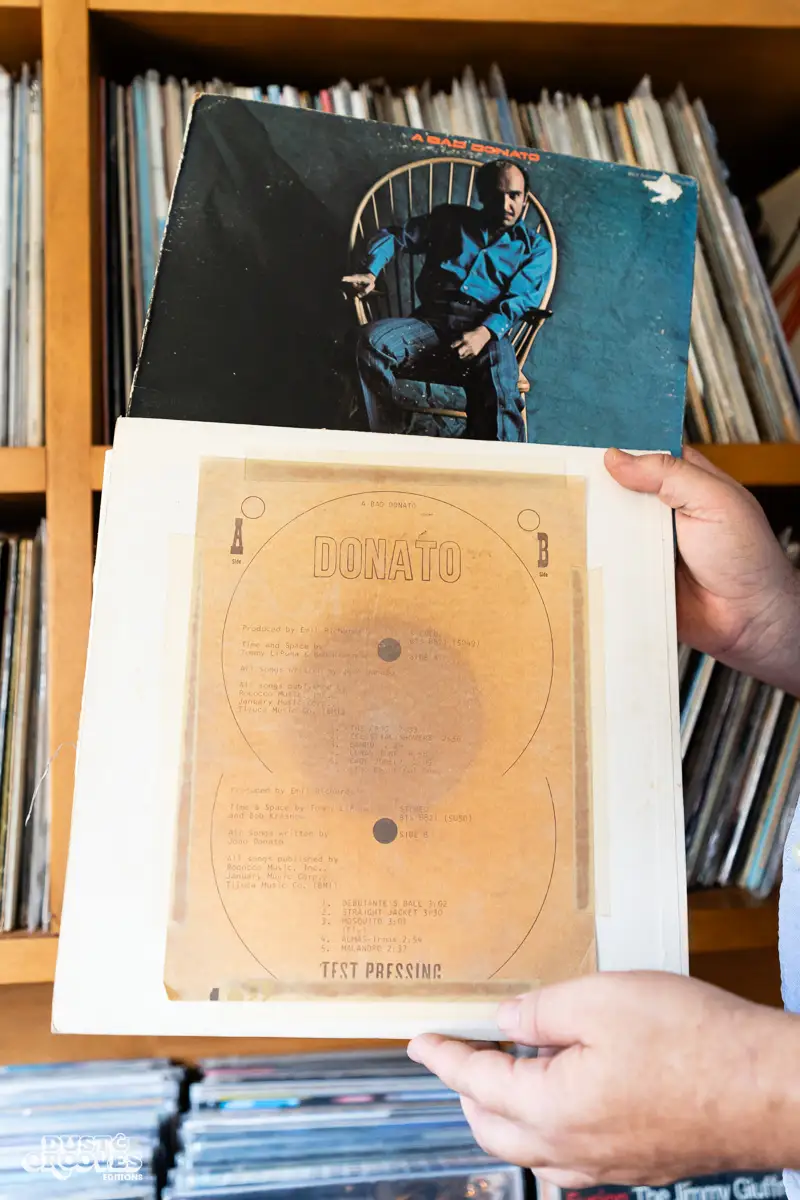

So, that for me is João Donato’s Quem É Quem. I love this record dearly. Recorded and mixed by Nivaldo Duarte at EMI. Incredible recording. The way it sounds, the way it’s mixed is unbelievable. I love that some strange things are happening there.

"[A Bad Donato] offended the purists but delighted a generation of adventurous diggers to come."

Kassin Tweet

The list of Brazilian artists that you’ve worked with over the years is very long and impressive. Has working with any of these artists led you to discover any interesting albums?

For sure. As one example, I love this guy called Edgard Gianullo. We played a gig in São Paulo, and then I got his record from the ‘60s. I called him, “Hey Edgard, how are you doing? I got your record, and it’s a very nice record, man!” We started talking, and he told me I needed to check out a record that he was listening to a lot at that time, The Guitars, Inc. with Tommy Tedesco and four other guitar players [Al Hendrickson, Howard Roberts, Bobby Gibbons, and Bill Pitman] making arrangements for five guitars. Very, very nice! I’ve been listening to that record a lot. I think the beautiful thing about records… the thing you did today when you came over with records, for example, you were like, “Check this record out!”

“Don’t buy something just because it’s very collectible or it's really expensive. If it's a shitty record, it’s a shitty record. Eventually, collecting should be fun and never treated like the stock market.”

Kassin Tweet

This is the best way to know records when you show somebody something like, “Look, I think this is really cool,” you know? Because I believe in your point of view, and you believe in mine. So we have that in common. If I show you something, you will give that a listen. In most of the great records I’ve known, someone said, “Hey, check this out!” This is something I miss nowadays.

When you put me on to do the radio program Universal Rhythms with Greg Caz, Eduardo Brecho, Manoel Filho, and João Duprat… I loved that we’d have to have a different record to share each week. Nowadays, everything is in a certain box… if you like this, you will like that. Algorithms. It’s really boring.

What tips or advice would you offer to a young collector just discovering this world of Brazilian music or record collecting? And also, what pitfalls would you tell them to avoid?

I think the most important thing that should be the basis of your record collection is to have a point of view and to have fun. I think my only tip is to be yourself and don’t buy something just because it’s very collectible or it’s really expensive. If it’s a shitty record, it’s a shitty record. Eventually, collecting should be fun and never treated like the stock market. The whole thing about having records is to enjoy them. Just go buy a good Caetano record and be happy about it!

Who would you next like to see on Dust & Grooves?

João Duprat. He’s been my good friend since teenage years, and we’ve spent our lives feeding each other music. Also Manoel Filho, one of the greatest record collectors in Rio, and DJ Gorky, a great record collector with great taste.

Further Adventures in Record Collecting

Dust & Grooves Vol. 2

Kassin and 150 other collectors are featured in the book Dust & Grooves Vol 2: Further Adventures in Record Collecting.

Become a member or make a donation

Support Dust & Grooves

Dear Dust & Groovers,

For over a decade, we’ve been dedicated to bringing you the stories, collections, and passion of vinyl record collectors from around the world. We’ve built a community that celebrates the art of record collecting and the love of music. We rely on the support of our readers and fellow music lovers like YOU!

If you enjoy our content and believe in our mission, please consider becoming a paid member or make a one time donation. Your support helps us continue to share these stories and preserve the culture we all cherish.

Thank you for being part of this incredible journey.

Groove on,

Eilon Paz and the Dust & Grooves team