Belgian DJ Stephane Lallemand is phoenix-like, rebirthing himself and shedding his given name in flames to become Lefto Early Bird. With the keen sight of a hawk, he hones in on sounds, always the first to get the worm. As he says in our interview, “I was the guy who had everything before everyone, being the early bird, even before I was “(Lefto) Early Bird.” Finally, like a few exquisite birds, he has the majesty to fly the world over, nesting in his global family’s dance floors.

I first encountered Lefto at Public Records (NY) through DJ Marco Weibel. I’d booked his collective Darker than Wax to play, and he insisted Lefto headline. I was glad he did. Lefto killed it with a style that’s tempting to label as eclectic, but “enigmatic” is more on point. He keeps you guessing, which creates an atmosphere that’s so charged it’s almost unnerving until he effortlessly smooths it all out and rebuilds the hype again.

Who is this international icon nested in Brussels, Belgium? To find out Elion and I made a pilgrimage to his place. I got straight to it.

"I was also a rebel in school. I was always the one who would confront the teachers."

Lefto Tweet

Do you have an early memory of understanding music, or even just of reacting to sounds as a child?

Going way back, there was a song I woke up to ‘cause they played it every morning on the radio, France Gall’s “Ella, elle l’a”. That song did something for me. It made me happy, and I loved to sing along to it.

But as far as a particular sound, what really incited my dive into sound was when a new genre of music, pre-techno-acid, hit Belgium. We call it new beat. I was interested in the music and the culture. People in white shirts and big, wide, black pants; Dr. Marten’s with the iron tip. I was hooked and dressed like that, wearing little acid, smiley pins without knowing what it meant as an 11-year-old. I wanted to be part of the movement even though I was very young.

From there, I transitioned into the hybrid genres. Songs like “Street Tuff,” by Rebel MC, a breakbeat-y spinoff, and that’s how I got into hip-hop.

Is it safe to say you brought hip-hop to Belgium?

That’s way too pretentious to say, hip-hop was already very present but I can say that I helped hip-hop to evolve and widen its horizons through my radio shows and events that I organized.

Which labels did you work with, and what projects came out of that?

For years, I worked as A&R for Brick9000, a label based in Ghent. As well as releasing music from locals I also traveled to the US for the label to find interesting artists. That put me in touch with some legends in the game at the time, from J Dilla to Madlib and his brother Oh No, an epic producer and Kankick, and also MCs like Declaime. Around that era, I met the Stones Throw people. It was the record label I wanted to work with/for at the time.

Tell me more about your work with Dilla.

I met J Dilla at a gig in Eindhoven. We were both on the same line-up. One of his record bags was lost by the airline, so we ended up playing together, him using my records.

It was backstage at that festival when the famous 4-part YouTube interview of Dilla was recorded, I sat next to the camera. We exchanged contact details and stayed in touch. We tried to collab on a project for B9000, but his health was already taking a toll on him.

I managed to book him on his last tour when he was already weakened and in a wheelchair. It was very sad to see. It’s really heartbreaking to see one of your idols suffering. It was the last show of the tour. In fact, his last show was in Belgium!

He stayed in the city for a few days after the performance, and asked me if he could borrow my MPC sampler. He wanted to produce some beats in his room on his iPod speaker system. I wonder if those beats on my machine were some of his last beats on the Donuts record he put out. I had a feeling he was not going to make it, and was sad to hear about his passing a month later.

His contribution lives on. You also worked with Gilles Peterson for a while, right?

I shared the turntables with Gilles Peterson a few times. One day, he said, “I need you to come play at my festival in the south of France.” From that day I became a resident of the festival and became a friend—someone who would share lots of music for his radio show and become a weekly radio show on WWFM until it stopped. I also released a compilation on Brownswood in 2012 and of course my album from 2024, Motherless Father. But Gilles knows he can count on me when it comes to music and sharing stuff he needs, or do a DJ set anywhere for him or a mix or blending two tracks, anything. I’m there to help. I DJ’d all of his Worldwide Awards as well, I mean, we talk a lot, he’s a friend, a good friend! Haha.

I also worked with K7 as the DJ who would mix their teaser albums.

Little snippets of their releases?

Yes, like the snippet tapes from back in the day. I did that for the Flying Lotus, Shafik Hussein, from Sa-Ra Creative Partners, and a few others. I put a remix album out on Blue Note in 2005 with my partner at the radio, Krewcial. I worked with Rawkus as well, promoting the label in Europe through the record store where I worked, Music Mania, from 1997 to 2007.

“The radio is the most important outlet I have to share music with people because not everyone goes to the club. Not everyone is into house or techno."

Lefto Tweet

How did you start with Music Mania? Were you simply a music fan who wanted a job at the store?

Yeah, I was a customer before working there; it happens to many people. They start by being customers, and then they become friends with the owners because they go there every day. You end up behind the counter because there’s new stuff that’s not on the shelves.

That’s where I was when they gave me the job. I was looking at records behind the counter, and a customer asked me, “What do you recommend?” I said, “Sorry, I’m not working here, but I can recommend some stuff to you.” The guy who became my boss saw this, and he asked, “Are you looking for a job?” I’d just finished school.

Were you around 18?

Yeah. I worked there a few days a week, choosing my days based on record deliveries. Tuesdays were very important days. Deliveries came with white labels and promo records from Fat Beats. Groove Attack out of Germany, our main dealer, knew my radio show on StuBru, and he’d bring us records that weren’t even printed yet.

Tell me about StuBru.

I started there in 1999. We were connected through the store because a station employee came to the shop every week to borrow records for their shows. They would bring them back the week after. It was a deal between the record shop and the station.

Working at the shop became a source of everything new and upcoming. I recommended music to the StuBru employees. Then Studio Brussels was looking for someone to do a hip-hop radio show. I was a pretty obvious choice. I was the guy who had everything before everyone, being the early bird, even before I was “(Lefto) Early Bird.”

The radio show was important for labels all over because they shared music through it, through the radio show, as an entry port to the Belgian scene, and further away. This got me opening for their artists on European tours, and that’s how I really started my international network.

“I think we all want to be part of a clan… Animals are always looking for a tribe, and I guess, in a human way, that's what I was looking for…. I've always been in search of something that can help me be a part of something.”

Lefto Tweet

It’s easy to see how you could go from a love of new beat [Belgian genre] into hip-hop and then street culture. Were you looking for a culture to embrace you, or something you could contribute to?

I think we all want to be part of a clan. Maybe it’s the animal instinct. We don’t want to be lonely. Animals are always looking for a tribe, and I guess, in a human way, that’s what I was looking for.

I grew up with my father, so I didn’t have my mother’s attention and love. I was probably looking for affection that I didn’t receive from her in these dance cultures because I felt like I needed to be part of a group, dancing, and sharing warmth and love on the dance floor. I’ve always been in search of something that can help me be a part of something.

Let’s talk a little bit about your dad’s influence. Did he take you record shopping? Was he influential just because you guys were in the same house, or was there a more specific musical education coming from him?

No, I discovered a lot of things on my own. MTV was a serious source of information. Yo! MTV Raps on Saturday mornings was a big eye-opener when it came to hip-hop. There was also The Grind.

The Grind was a party broadcast on MTV. It might have been a Brooklyn block party or a beach party in Miami. You’d see a DJ DJing, and the dancers dancing… but with style. You know, nice clothes and the fancy camera angles, close-ups and filming the footwork..

All that stuff really triggered me. I saw these DJs playing with techniques, SL1200s, MK2s, and I was like, “Wow.”

Belgium television had a show called 10 Qu’on Aime, which was very pop. But they had this rapper called Benny B and a DJ called Daddy K, who did crazy stuff on the turntables, scratching mad and spinning on the turntable and breakdancing.

Wow.

Mind-Blowing. I got totally into the gear, and the turntables because of that show. We had a turntable at home, a quartz, Pioneer. I started to scratch my father’s records, and he got really angry. Then I said, “Well, maybe we should buy one for my bedroom.”

Those turntables were quite expensive, and my father was not the richest. I’m still traumatized by it, actually. We were in that range. We were basically poor sometimes… Sometimes they would freeze my father’s bank accounts, and that deeply impressed upon me that we were not that rich.

My father took a bank loan to buy my first turntable, which I still have in the studio. I started with one turntable and a little Realistic mixer I found. I used to mix cassettes through it.

But really, I learned the mixing skills from a school friend who had two decks. He was already properly mixing, and he showed me the basic way of doing it. Then, I would just practice in my room all the time.

When did you go to your first rave?

I went very early, before I was 16 because I was dating an older girl. She would take me on her motorcycle to crazy clubs like The Extreme. It was a mega-temple, super-club with multiple floors.

There, I discovered what a stroboscope does to a body. I liked losing my balance and feeling my heartbeat go as fast as the stroboscope. There was this moment at The Extreme around 1 AM called The Helicopter. The stroboscope would go very slowly and then progressively super fast. It put me off balance, so around that time, I knew that I had to go outside for a minute until The Helicopter was over.

Geert Sermon (Sound of Belgium/Dr Vinyl) told me that Belgium had all these great clubs out in the middle of nowhere, that you had to drive to.

Yeah, unless you lived in the area. We would go on a motorcycle.

Clubbing with motorcycles in the middle of nowhere, how romantic.

Yeah, you would see a lot of motorcycles on the side of the club. It was a big thing. We were part of the motorcycle culture. My best friend had one that was supposed to ride 25 kilometers per hour but he modified it to do 90 or 100. You could put sand in the frame to maintain the balance at higher speeds. People would add different exhausts to make more noise. It was a real culture.

Did you get into bodywork with bikes? Many artists, such as Robert Irwin, started in car culture.

I got into graffiti instead, but I guess I didn’t get into the bodywork because it was a lot of money that I did not have…

When did you start writing?

Around the same time that I started DJing. I was in one of the biggest Brussels (graffiti) crews. It was called P50 related to those packs of fries you could buy back in the day. A P50, was a paquet de frites à 50 because it was 50 francs. Stupid thing, but we managed to get a lot of media attention because we’d just destroy the whole city. Some of our friends ended up in jail… so much vandalism.

I have to say, I tried not to disappoint my father. When I saw my father being disappointed in me, it really hurt. So when my friends would go writing at night, I would go with them, but I was the watchman. I tried not to get too crazy on the walls.

I was wondering about that. If your dad was a single parent, how much leniency did he give you to go out?

I was very free. Whether I lived in the countryside near The Extreme, in the Brussels areas of Anderlecht, or in Molenbeek, I was a street kid. I would come home very late. My father would drive around the neighborhood trying to find me. I would come home at around midnight when I was about 12.

That’s pretty young.

I mean, I did some crazy stuff, like setting a mall on fire, but that’s another story. And not on purpose, just being stupid and playing with fire… literally.

Have you always played with fire?

Yeah, always… still.

Your dad was a travel agent. Did you go on trips with him?

No, I would stay with my grandmother, and he would bring stuff back. That’s what I do now with my son. I always bring something back from wherever I go.

When was the first time you left Belgium

When I was 15, to New York.

That’s a pretty influential time. It was the 1990s. What was New York like then?

It was still pretty ghetto—even Manhattan. I remember passing in a taxi through different neighborhoods where there were collapsed and empty brownstone buildings. It was a time in New York when parts were not cool at all. Even Broadway and SoHo were kind of sketchy.

I remember trying to enter an Adidas store, and there were kids holding the door telling me to leave. They were robbing the store. I hung out on the corner watching, and then all the kids ran out of the store holding clothes.

Did you go to Fulton Mall?

I did go to Fulton Street and to Beat Street Records with the jewelry on the ground floor. Then you go down and see the huge amount of records they had. It was nice to see that those records were a lot cheaper in the U.S.

They had all those bootlegs.

Yeah, you could feel a real DJ culture there, and in NY in general. I met Mos Def at Fat Beats. He just walked in randomly. I mean, that’s New York.

“These records both came into the shop at the same time. They are two of the most important rap records for me, bringing conscious, soulful rap back during the era of gangsta rap—a relief of some kind."

Yeah, connections come easily there. Living in Europe, you’re connected to other countries and more aware that you can jump around the planet. Does Belgium feel like home or are you a citizen of the world?

Even though it rains a lot, and it’s cold sometimes, I don’t think there is a place where I could feel more at home.

But I love traveling. When I travel for a gig, I spend two weeks in the area. That’s how I recharge my batteries.

By not jumping in and jumping out?

Yeah, just to feel like I have enough of that place in me, and with that in me, I can go home… until the next time. For example, I go to the US a lot. I feel very connected to it. If I lived there, I would probably choose Seattle.

Because it’s famous for its rain, like Belgium?

There’s a different energy in Seattle because of its volcanoes. There’s a different connection to Earth. If that volcano tomorrow decides to explode and blow up, you’d be in trouble. So you respect nature more.

When you land in Tacoma, it’s a beautiful sight, especially on a sunny day. On the horizon, you see all these volcanic peaks. Mount Rainier is as big as Fuji. It’s so beautiful and green.

I have a strong connection with the Pacific, and with cities, too: Chicago because of the jazz scene, New York because of the hip-hop scene, both for their house scenes.

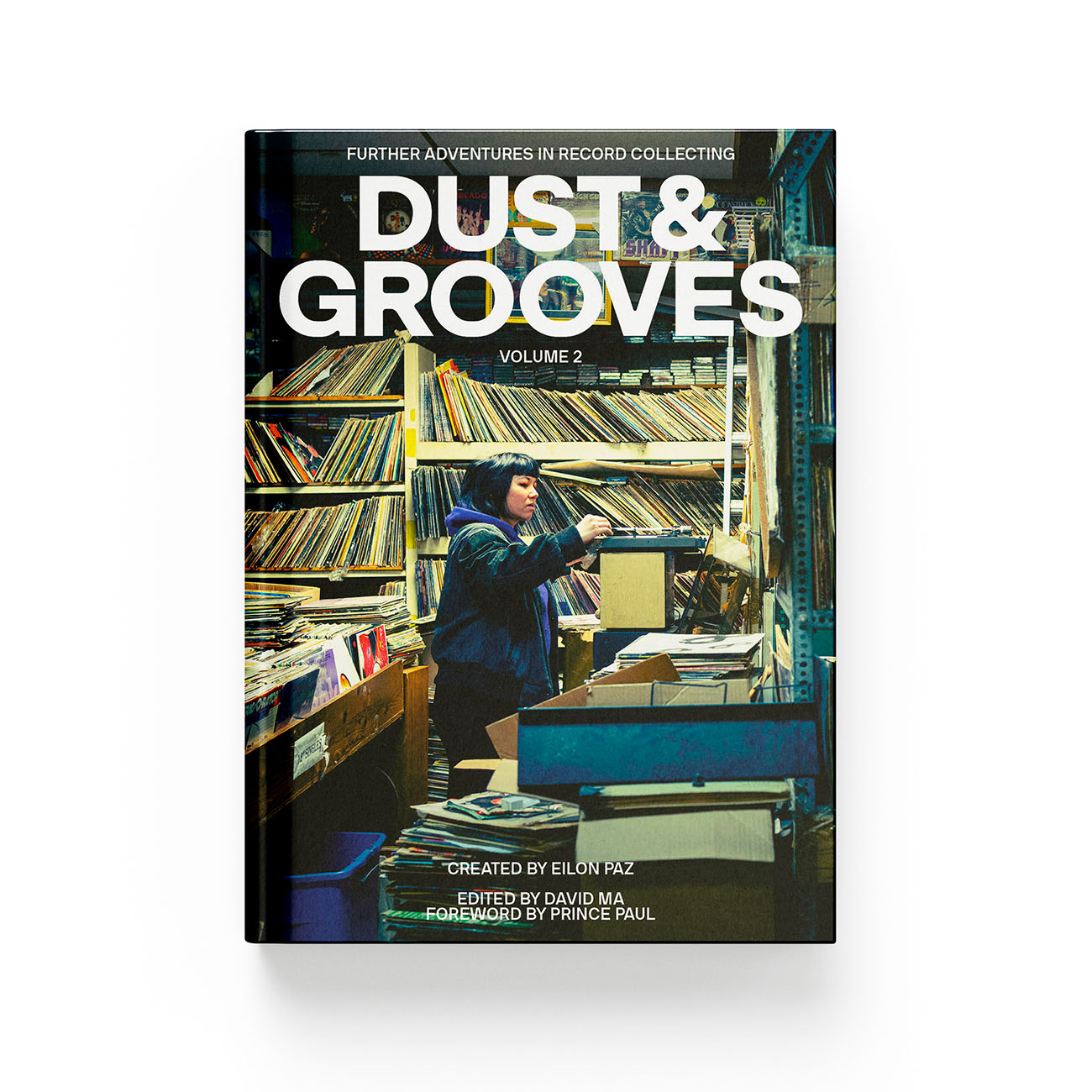

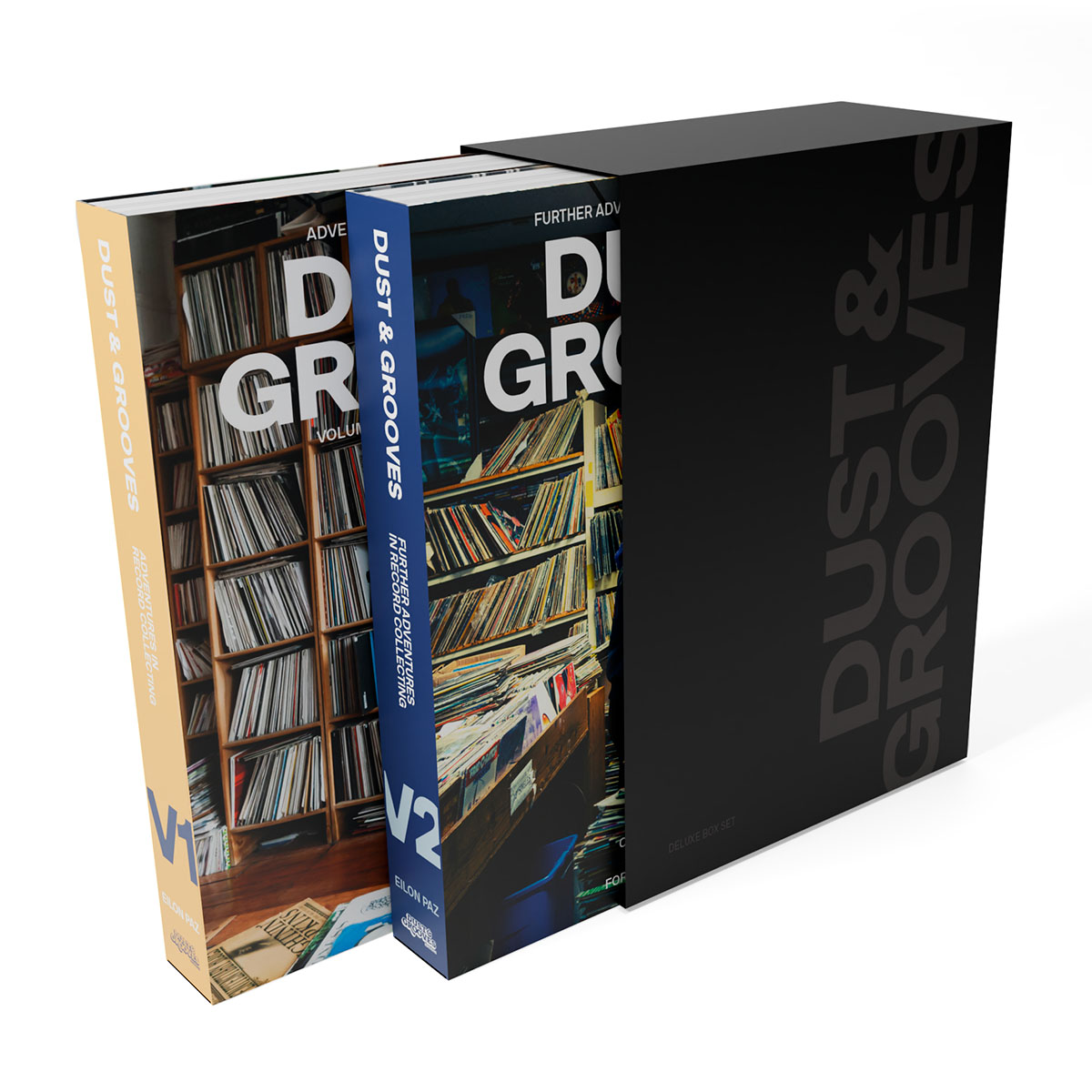

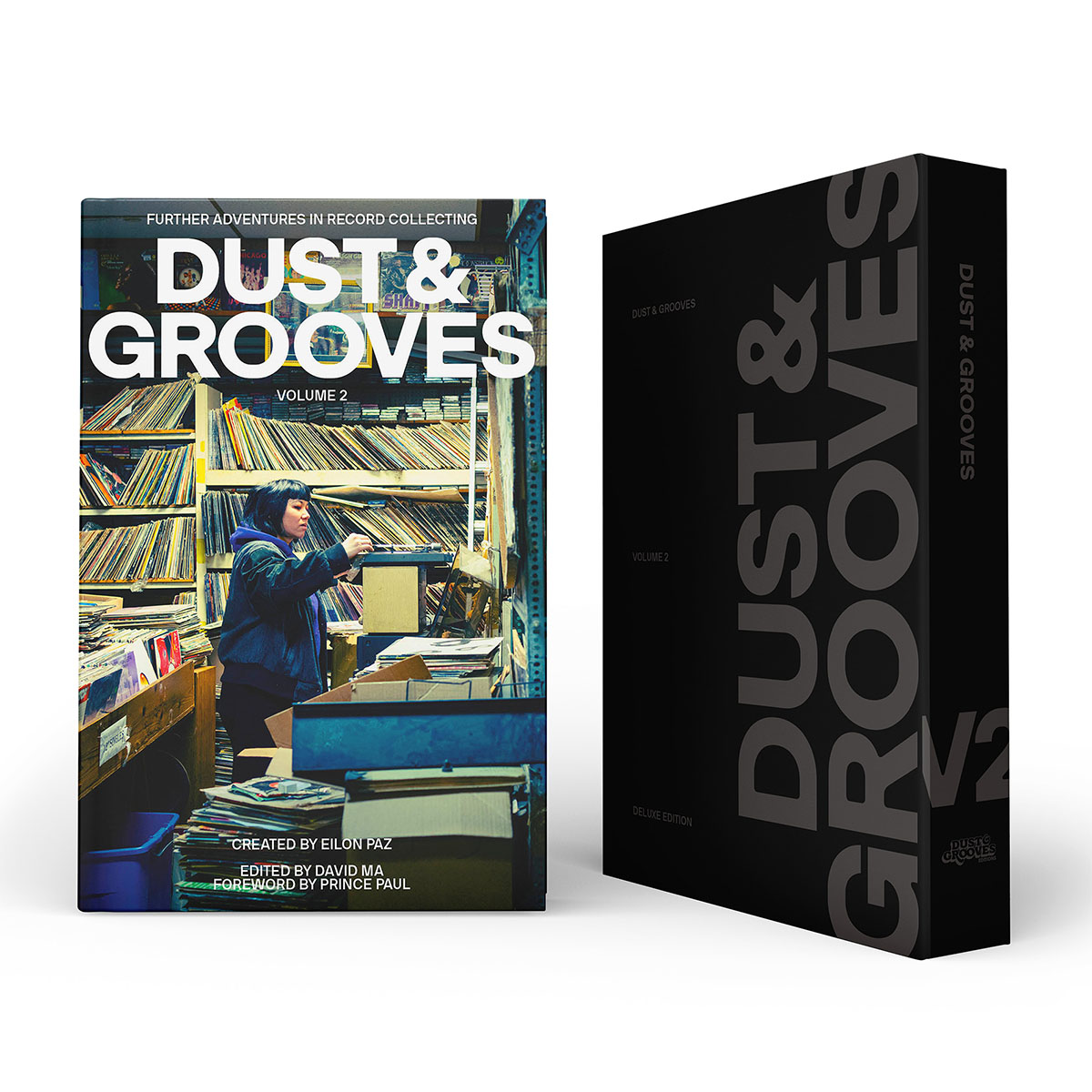

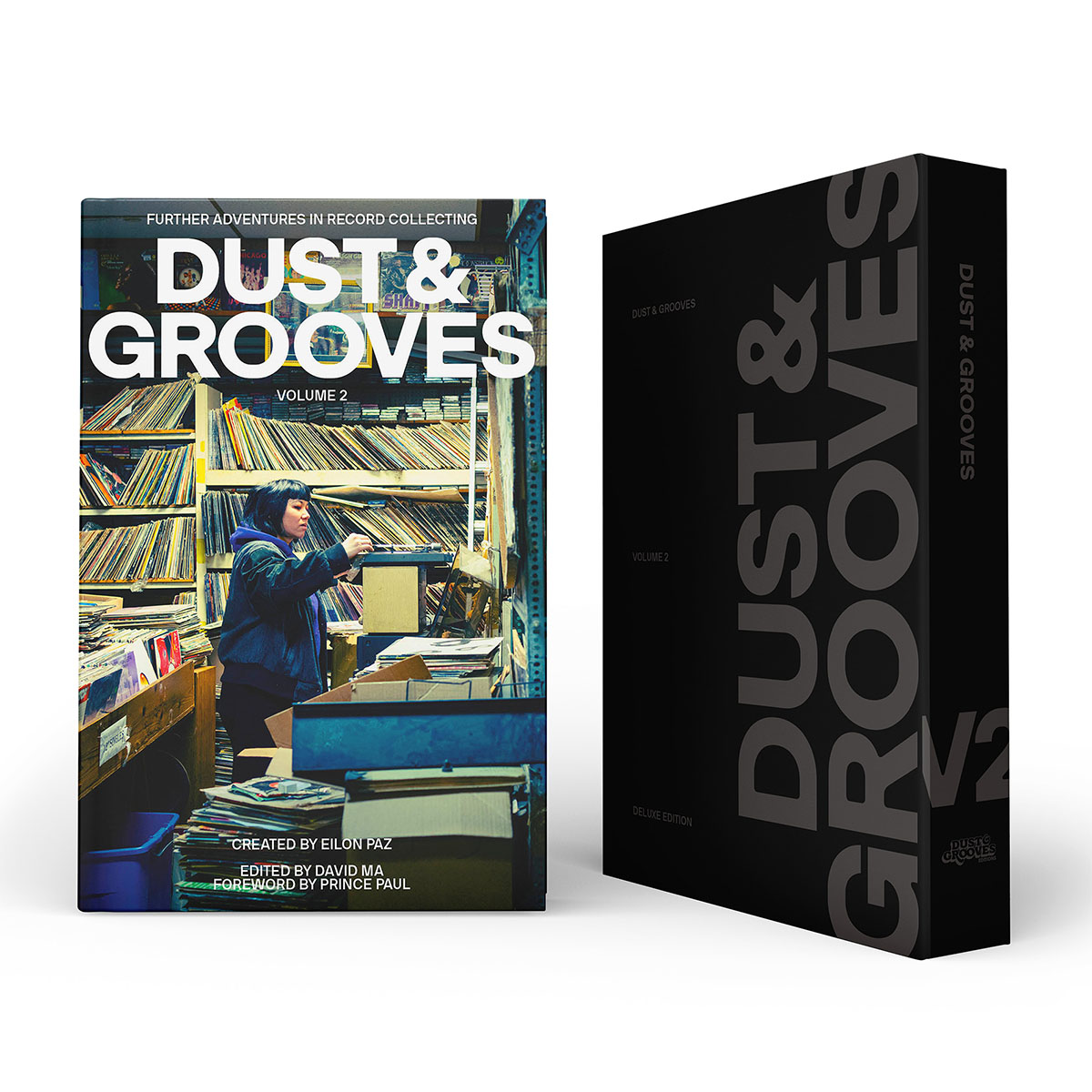

Dust & Grooves: Further Adventures in Record Collecting – Deluxe Slipcase First Limited Edition

Further Adventures in Record Collecting

Dust & Grooves Vol. 2

Lefto and 150 other collectors are featured in the book Dust & Grooves Vol 2: Further Adventures in Record Collecting.

We’ve talked about Belgium’s music culture, but it’s also home to so many other art scenes. I see Magritte’s sense of humor everywhere; he’s a reflection of what being Belgian is first, then a surrealist. What about being Belgian is core to your creative output?

I don’t know how you say it in English, but there’s a word we use, autodérision. It means not taking ourselves too seriously because we know where we come from.

We know that we’re just a buffer zone between French and Dutch culture. They created our country just to make sure that the French and the Dutch would not fight so much. We’re not even meant to exist, in a way.

Belgium is a place with a lot of political fighting because we are two different countries in one. The two cultures here are totally different. For example, a foreign act might fill up a stadium for 30 days in a row in Flanders (where they speak Flemish) and can be totally unknown in the south, where they speak French. It makes our country so surreal.

Somehow, Belgian music has always transcended that, especially Belgian jazz or dance music. It doesn’t matter if it came from Flanders or the French-speaking part. It’s just Belgian. The jazz scene, for example, is not programmed or calculated to fit into the jazz mold. It sounds very different from what has been done in France, the UK, or the US.

Because traditional jazz is entrenched in making odes? And if you don’t play the standards in the standard way, you’re not playing jazz?

Belgian jazz has an experimental side to it; an unquantized kind of vibe that makes the sound unique. I’m very proud of the Belgian jazz scene. For such a small country, proportionally, it’s huge. Belgium has always been very influential in the world. The saxophone is Belgian, for example.

I’ve been able to release jazz compilations with so many artists and organize podcasts in Brussels running two years with a different band every month, from just Brussels. It’s a lot, over 30 interesting bands playing different kinds of jazz.

Take hip-hop. It was very influenced by jazz because people used a lot of jazz samples during the ‘90s. Today, jazz is very influenced by hip-hop. So it’s a different sound, and I think it thrives today more than it did. It’s accessible to younger people in a way.

There are so many DJ hats you wear: your live performance hat, a radio DJ hat, and of course, within that, there are sub-hats: how you play a rave vs a small club vs playing as a radio DJ on actual airwaves vs your Kiosk & Lot internet radio shows. It’s been around 25 years that you’ve been DJing?

29 years now.

I do wear a lot of different hats. It’s cool to have different hats, and it’s a bad thing as well. I like being a DJ who can play different styles of music in one night and be on point. You hit the snare, you hit the right spot. Whether I’m playing jazz, Latin, house, techno, juke, footwork, or hip-hop.

It’s hard to convince promoters because they like DJs who are known only for one genre; they think that you can only be marketed in one genre. I am just someone who loves many genres and puts a lot of energy into understanding, respecting, and pushing genres.

Right, and you’ll do it well.

I’ll do my job. It’s just hard for them to realize that the people, the crowd, they are open to it.

How did you manage to build your fans’ trust so that they will follow you through every genre? It’s something your audience can relate to as “Lefto-esque.”

The radio show online has done a lot, and having my shows on Mixcloud. I have 130,000 followers on Mixcloud. So, everywhere I go, I come across people saying, “We listen to your show every week on Mixcloud.” I think that’s really how you create a worldwide base.

On a local scale, I’ve done a lot of curation over the years for festivals and parties called Lefto Presents. Sometimes, it was a rapper and an after-party, and the DJ would just play rapid house and all that stuff. And then another night, it would be jazz and a DJ who played house. I would put people into a certain position where they just had to deal with it.

“More than a genre, it’s the energy. I want to give that out as a message to people. You can play Latin music, or you can play jazz and think it's not something your parents listen to. That's what's important.”

Lefto Tweet

And it makes sense to you, obviously.

It always makes sense to me. It’s all about the energy that comes out of the music. More than a genre, it’s the energy. I want to give that out as a message to people. You can play Latin music, or you can play jazz and think it’s not something your parents listen to. That’s what’s important. A DJ or curator has to have good taste. Their ear determines what is cool.

That’s the beauty of being the curator of a stage. You can recontextualize a genre into something unique, existing only in that specific moment of time.

Yeah and of course, with taste, people will tell you that it’s subjective, “That what you think is cool is just corny.”

Exactly, a curator showcases’ their taste.

It’s my job. You have to listen to what kids listen to. My best friends are all dads. They’re having kids, and they’re busy. They don’t have time to go out anymore. They don’t have time to follow you everywhere anymore. So I end up chilling with people who are 10 or 15 years younger than me, and I have a lot of fun with them. Sometimes they just laugh at me like, “…but you’re old.” But for them, it’s nice to see someone older, who’s a responsible father, chilling with them. Sometimes I give them advice, or say something that could come from their father, you know?

Yeah, it’s such a nice feeling to be helpful in that way, and you’re probably sharing music history, as well.

Exactly, and I learn from them as well. It’s not a one-way street. When it comes to music, they listen. I have a point of view that could be helpful to people coming up.

I hear new DJs on the internet radios who are trying to mix, and it sounds horrible. I said that to the youngsters, and they’re like, “Why not? That’s how they learn.” I’m like, “Yeah, but can’t they just learn in their bedrooms? And when they’re good, they come out.” They’re like, “But some of them don’t have all that stuff in their rooms, and so they have to use the gear that’s available somewhere.”

That’s a good argument. What is the answer really for you? Why shouldn’t these beginners be in front of an audience?

Because they don’t have the time to understand the art and they also lower the level of the art of mixing, and then mediocre mixing becomes the norm.

Right, or to develop it.

No patience.

A few DJs I know who started around 14 in the 1980s would learn with their friends, like you did. One guy out of the group gets their hands on the gear, and everyone goes to that house to practice. These were street culture crews. They were skateboarding.

That’s me, and yes, I was skateboarding as well.

“It takes time. You don't become a great skater from day one. And you don't become a great DJ from day one either.”

Lefto Tweet

These crews were serious schools in all of that culture. In fact, they used the term “schooling.” You’d learn with those friends with a touch of tough love usually, and then you’re ready for an audience.

It takes time. You don’t become a great skater from day one. And you don’t become a great DJ from day one either. You need time not only to learn how to mix but learn how music works. There’s an art that you need to learn and time to gain your confidence.

DJs who just started are put in front of a large crowd, and they are definitely not confident. That can break them.

How long into your career before you played a big crowd?

Maybe five years. My first gig was not before I had a few years of homeschooling. It’s a different way of thinking, and it makes sense in this world where everything is accessible immediately. The attention span is so short that people don’t have time to wait, grow, or watch things. They just want it all instantly, and then they move on. In the pre-internet era, your career was built on merit and reputation, and by people spreading the word about someone they saw DJ at a party—it was great. That word would spread and you would get booked eventually.

Yeah, whatever you’re offering is expected to be fully developed before it can just “be.”

And sometimes it dies before it’s even born.

Let’s talk about your 29 years as a DJ. How has your sound developed as you’ve developed?

I started as a straight hip-hop DJ who tried to mix to perfection.

Were you scratching and cutting?

I was a turntablist. I did a lot of scratching and turntablism. I am still very connected with some of the best legendary scratchers of my time. A-Track’s a good friend. I did back-to-back with J.Rocc from the Beat Junkies, who is a world champion in battling as well.

I got into turntablism and added it to the DJ sets and eventually to the radio. That was strictly hip-hop. I brought into the game the breaks and the originals, going a little bit more uptempo and funky.

Then I went from the funky disco stuff into house. I think it’s an evolution a lot of DJs around my time had: DJ Spinna and A-Trak. It was then that I started to produce myself, to go dig for records that had samples from my favorite hip-hop records.

What is some of the gear you’ve used in your productions?

I’ve worked on so many different machines. I started with an Akai S-950 sample with Cubase. Then I went to the famous hip-hop machine, the MPC and the SP-1200. It’s a machine that Pete Rock and Easy Mo Bee used a lot. Then I got the MPC-3000, the same as Dilla. I started to produce on Ableton a lot later.

When you started producing, did your knowledge of music get deeper?

I started to understand that the 1990s hip-hop I loved so much got their samples from other genres of music. So I thought, “Why am I not looking into all these records myself to find interesting samples?”

Have you always wanted to be an original?

They always treated me differently in school. Oh, I would get looked at for coming to school and having blue hair or blonde hair.

I was already into hip-hop, and hip-hop was special. Hip-hop was nothing around that time for most people. The hip-hop way of being dressed was just different. Baggy pants? That was very new for the people I was with in school.

So you took some heat for it?

I definitely took some, yeah, but was it that I felt different, or that people always made me feel different? Actually, I felt like I was just like them.

When I was a kid living in Molenbeek, they made me feel different. They made sure that I understood I was a white kid. They would make you feel like we weren’t the same because I didn’t have the same struggles, but they were still my friends.

So, ultimately, you were accepted. That’s something.

I was always accepted somehow, maybe because I was being myself.

I was also a rebel in school. I was always the one who would confront the teachers. When I was 10, I was so full of what I was saying that I would make a professor think that the way you spell mountain was mountian with “ia” instead of “ai”. She went into the dictionary! That’s how full of myself I was.

You were confident.

Yeah, confident on my stuff. I was not scared of saying things to teachers.

Did you think it was important to finish school?

Yeah, I always wanted to finish school. It was also important for my father. I mean, I like school. I just didn’t like the teachers, or I didn’t like to be taught.

Going back to your musical style, how do you prep for your gigs? What makes you confident that a song is going to hit?

I don’t really know how it works inside of me. When I hear something, I know when it’s special or not. I feel it, and when I play it out, people feel it too. There are certain formulas in music that I can read, or there’s a special something in the music that makes you know, “Oh people, they gonna trip on this.”

Is there something physical that happens in your body while you’re prepping?

A little bit, maybe, like the feeling of being surprised by an element in the music, or a break or some unexpected pause, or something that’s just in the song.

I listen to a lot of music every day. That’s my main job here. I wake up and take my son to school. I come back. I go through my emails, and some promo-emails. I start surfing the web and find an interesting, rare album or a song with a great break. I dig every day, for eight to ten hours.

Yeah, you need to invest that much time. Especially, with your weekly Think Outside the Kiosk shows, you have to have new music every time.

I don’t have to have new music. The radio is not something that pays me. I could focus only on club music because that’s the sound that generates money. But that’s not me. For me, the radio is the most important outlet I have to share music with people because not everyone goes to the club. Not everyone is into house or techno. A lot of people like different genres, just like I do.

I’m assuming you’re getting promos from this network. How many new releases do you receive directly from the producer of the music, on average, per week?

Per week?

Maybe per month.

No, I was gonna say per day. I would say 50 a day, maybe more.

More than a genre, it’s the energy. I want to give that out as a message to people. You can play Latin music, or you can play jazz and think it's not something your parents listen to. That's what's important.

Lefto Tweet

So there’s this really nice exchange. You say that having the radio show helps people all over the world hear your sound, but then you’re actually spreading the sound of your musical family via the shows.

Yeah, and… I give feedback. If it’s good, I don’t always give feedback because they will hear it on the radio. If I don’t play it, I usually just reply, “I’m missing something here.”

People are so afraid to critique these days.

You have to do it, “with a certain tact,” as we say. You have to be respectful towards the artist because it’s going to touch their ego. If you make music with your heart, and someone hits you back and just destroys everything you created, it comes in very hard. Finding your own sound takes time. I say to them, “Your sound is good. You’re on the right path..”

You are a teacher at that moment.

Yeah. I also receive a lot of music that was made just for the dance floor. I’m not interested in that. I like timeless music. I like to play music that I can still play in 10 years. I’m not into “the sound of now.” To me, it’s just something that’s gonna fly over.

I feel there is a rapid-fire, consumer-culture mentality that DJs feel pressured to keep up with. For example, when we only played vinyl and were only playing in clubs, people actually enjoyed hearing the same records every Saturday night. When you were playing records, would you start with a whole new crate for each gig?

I would always add more than take away. I used to do a weekly show in Ghent at a club called Chocolate. It was on Wednesdays, and my then-girlfriend baked pancakes and ran around giving out Chupa Chups lollipops to people. The club was only for 100 people, but we managed to have 1,000 sometimes. I invited people like Tony Touch. We would ask for like five euros for entrance, and we would go home with 5,000 euros. Like wow, we had 1,000 people in there?

That’s amazing.

In a place that’s not bigger than this [500 square feet]. I had six or seven crates because it was strictly vinyl then. It was a lot of carrying.

Were you playing all night?

Yeah, and you know, when you’re playing in hip-hop mode, it’s always like, after the first or the second chorus, you just switch.

Did you have someone help you? Sorting records?

No, but to carry them, yeah. I didn’t have a driver’s license, so I needed a car every time.

You still don’t have a driver’s license, right?

No, I don’t need it. I will never get it, I think.

You like to bike.

Yeah, biking always. And skating to the corner store, of course. Biking is part of our culture as well, especially on the Dutch side.

I feel like there must be a connection between your practice of biking and your visuals, With the movies that you made, and the little videos of your travels. There’s a lot of movement in them.

Maybe. I’ve never thought about it like that, but yeah, I have over 300 videos on YouTube and Vimeo that I made for my friends who couldn’t come abroad with me, so they could see what I saw. That’s how it started, and then I discovered I love editing and making these short montages.

Are you self-taught?

Yeah. I learned it all by myself, and the photo magazines my father was collecting probably helped. I think I checked out all of his magazines and they were fashion ones; the aesthetics and the layout were great.

What other work do you do in the vein of visual arts?

I’ve made a few record covers. I make all the designs for my radio show. I make stickers, I make video montages for music and interviews and I also touch a bit of visuals for live shows.

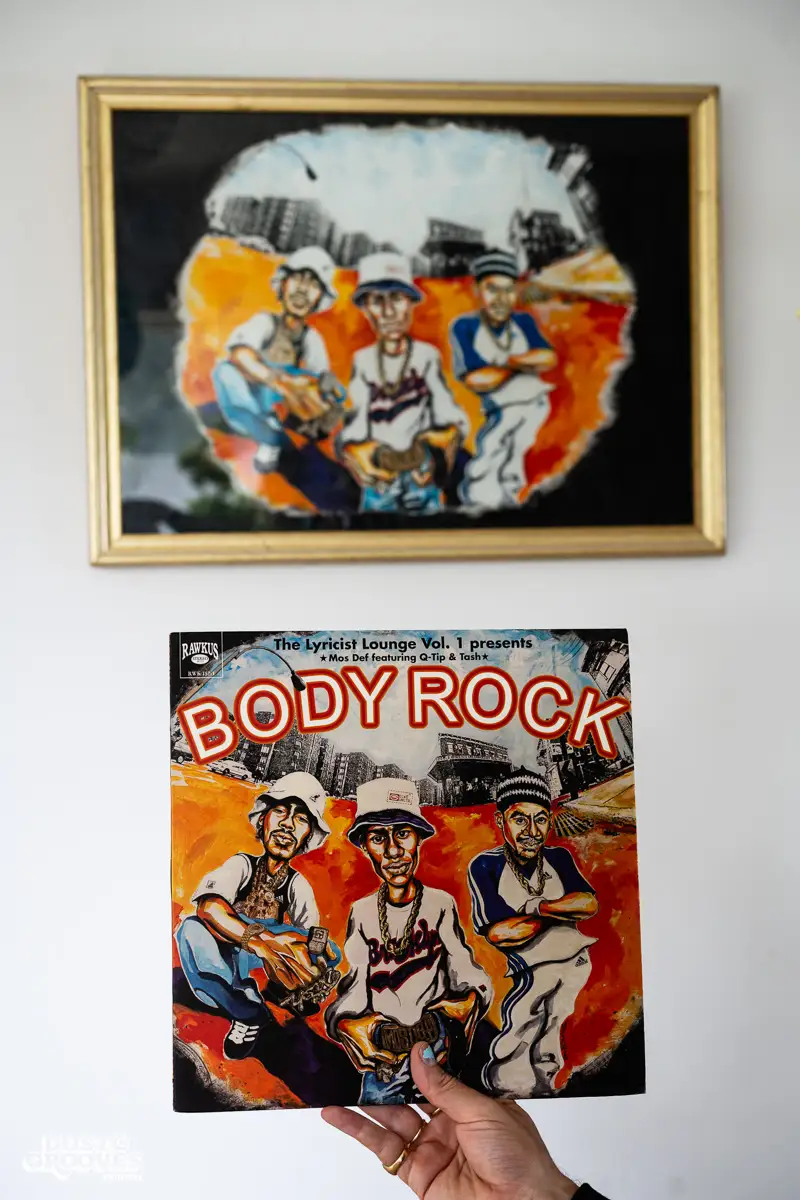

What about the album cover painting by Ge-ology? That’s a big part of NY hip-hop history? How did you two meet?

I should call Ge-ology to remember how we met; maybe I booked him for one of my nights, I don’t remember, but every time we see each other we talk a lot, and I’ve been a fan for a long time of his music and his art. One day, I asked him what happened to the painting of the cover of the famous Rawkus record “Body Rock” song, and he said it was still framed, in a box in his basement in Brooklyn. I told him I was interested. And that’s how it ended up in my living room on the wall.

"It’s one of my most treasured pieces because this record represents a particular sound of NYC rap history.”

Is there a connection that you make between the way you see the world and the way you create sounds in your mixing style?

I try to connect everything just as I do during my travels so maybe that’s the magic. I like to make people feel comfortable on the dance floor with the genre changes I throw at them. I like to talk on the mic because that’s how you interact with people. That’s how you make them feel you’re human, not far away but close and there for them.

Yes.

We need to humanize the DJ. A lot of DJs are sometimes too far, too high, too disconnected. People dance, but they don’t have any connection with the DJ; they just have a connection with the music. It’s okay. I think it’s a skill to get them closer to you, and it’s nicer for them. I think it gives them an experience that they do not always have. Not a lot of DJs talk. It’s a very old-school thing but you know, kids are styled old-school these days haha.

There’s that saying, “Never trust a DJ who doesn’t dance.” Bill Brewster from the book How to DJ (Properly).

I should make a sticker for that. So many DJs don’t dance! It’s like they’re too concentrated behind the decks. It’s very stressful, so they’re not even listening anymore to what they play or watching the crowd. DJs have to maintain the crowd connection, choose the music, and have their mixing on point. Doing all that stuff at once takes time to learn.

And you add maintaining the chat room to your Kiosk shows.

I do like the interaction with the people around the kiosk in the park and maintain an interaction with the listener abroad as well through the chat room yes; I react to what they say in the chat room and it gives the whole show a whole new dimension.

The chat room is also your audience.

There are two audiences. The online audience and the one outside. I don’t know which I’m more focused on.

People who are there just come for the show. Last Sunday, it was empty when I got there at around five, and at quarter to six, it started to fill up. At six, it was full and stayed full even on a muddy, bad, cold day. Even if I start with 20 minutes of ambient music in the beginning. It is what it is. They know it’s all coming. I like to build up. That’s why I like to play all-nighters or to play early.

So many of today’s DJs don’t get the opportunity to play an all-night set because they always play as part of a multi-person lineup. I think it’s weirdly competitive and slightly unnatural.

The last time I played at Fuse, they put me on from 5 AM to 7 AM. I was like, wow, and I came from an all-nighter in Dubai. I took a nap but ended up not hearing my phone at all. Luckily, my neighbor was going to Fuse, and he knocked on my window, waking me up in time.

The DJ before me was playing kind of softly. At Fuse, you can get behind the DJ, just like at a Boiler Room. People were coming to me like, “Lefto, it’s 5 AM, we’re at Fuse, you know what to do.”

I prefer to start around midnight with hip-hop or Latin music, or some Turkish psych-rock and build up. I go into boogie and finish around 3 am before the next DJ plays. I end with like techno or house. I like that because then they’ve gone on a trip with me.

I understand the codes of clubbing. At 2 or 3 AM, that’s when people really want to get into something. So, I understand that it’s not the right moment to play some Latin stuff. There are rules you have to understand. But for the Fuse gig around 7 AM, I started to play acid jazz.

That makes sense.

Some people became hysterical because of the piano solos.

Do you like messing with people a little bit?

I do. Even on the radio sometimes. I like to see people go completely nuts on something like Baile Funk, and then I stop and I start with something very soft again. It is a radio show. I can do what I want.

I learned by experience. I’m not a traditional kind of DJ who might say, “I don’t play certain BPMs before a certain time.” I don’t follow that. I know there are certain BPMs you can’t play. You might hear 120, 125, or 130 BPMs early on, but not for too long. I can balance it out and if I play house for too long, my brain’s going to say, “You need to switch to something else.” While other DJs could go on for hours (in one genre), at some point, my brain is going to say, “I’m getting bored now.”

You have a sober brain, right?

I do have a sober brain. Very sober.

Did you at one point say I’m never going to drink?

I tried most things, but my taste never really liked it. My body said, “It’s not your cup of tea,” so, I just never really continued drinking or smoking.

When you listen to music and see colors, how are you seeing?

It’s the way the sound comes in and how I respond to it. That’s why you call a dark sound dark. It also makes people feel dark sometimes, which I’m not too fond of, especially in these times.

Putting on the TV or opening your Instagram, you see so much darkness. That’s not the thing that I want to feel when I go to the club. Some people say, “The dark stuff just takes so much stuff out of me,” but that’s the problem. It takes stuff out of you. It doesn’t put stuff into you.

You get rid of the darkness in you, maybe you’re angry, the music makes you angry, and it takes stuff out of you, but it doesn’t put the positive into you.

That’s really interesting.

When you go to the club, you take it all in, so shouldn’t what you take fill you with positivity? You go on holiday to get vitamin D and sun. That’s what you want or at least that’s what I want you to feel.

Do you feel you have a responsibility to shift your audience’s energy into a more positive light? How do you see your role as a DJ? Are you a community leader? Are you a ceremony master?

Maybe I’m all. I don’t like to put an etiquette. I’d rather let other people say that about me, but I try to spread a positive node out there and create community energy. If people feel good around me, it makes me feel good.

Are you connected to spirituality in some form?

I respect a lot of religious music. I’m very connected to spiritual jazz. I love gospel. I love the energy that’s used to record that music and how honest its message is. Gospel is also about community. When I play gospel, I see people’s faces change. I see smiles. A lot of spiritual jazz tells you a lot about the time it was recorded and the struggles from around that time. It’s a history class, it’s like early hip-hop but then from the late ‘60s and ‘70s.

I do think that “Religion is Division” [points to his tattoo of the phrase], but I respect people who believe in a religion. In some countries, they rely on religion. In war zones, they rely on religion, because that’s the only thing they can hang on to, religion can be hope as well. I understand and respect that.

You called yourself an animist, at one point.

Well, the only God I believe in is nature. I believe that if tomorrow Earth says, “You gotta go,” you’ll go. That’s why I think we should find ways to respect it more.

“The only God I believe in is nature.”

Lefto

Lefto Early Bird has proven to be one of the most important tastemakers on the old continent. Described by Fact! Magazine as “your favorite DJ’s favorite DJ,” he is consistently ahead of your average early adopters. He doesn’t wait for the next thing; he seeks it out.

You can keep with Lefto Early Bird online:

Instagram

Mixcloud

Kiosk Radio

Interview edited by Fiona MacPherson-Amador

Dust & Grooves: Further Adventures in Record Collecting – Deluxe Slipcase First Limited Edition

Further Adventures in Record Collecting

Dust & Grooves Vol. 2

Lefto and 150 other collectors are featured in the book Dust & Grooves Vol 2: Further Adventures in Record Collecting.

Become a member or make a donation

Support Dust & Grooves

Dear Dust & Groovers,

For over a decade, we’ve been dedicated to bringing you the stories, collections, and passion of vinyl record collectors from around the world. We’ve built a community that celebrates the art of record collecting and the love of music. We rely on the support of our readers and fellow music lovers like YOU!

If you enjoy our content and believe in our mission, please consider becoming a paid member or make a one time donation. Your support helps us continue to share these stories and preserve the culture we all cherish.

Thank you for being part of this incredible journey.

Groove on,

Eilon Paz and the Dust & Grooves team