There are reissue labels and there are archive labels. Somewhere in between, in a league of their own, lies Rome’s Four Flies Records. Specializing in lost Italian soundtracks and library records of the 1960s and 1970s, much of the label’s output was never previously available outside the world of Italian film and television production.

Beginning in 2015 as a reissue label, Four Flies soon expanded their vision to create a niche, going to great lengths to present previously unreleased material and lesser-known scores. Personal relationships developed with the composers, and their heirs have allowed the label access to vast archives of tapes that they meticulously review and reevaluate in search of forgotten works worthy of listeners’ attention.

The man at the helm of this noble endeavor is Pierpaolo De Sanctis. Raised on a steady diet of B-movies, De Sanctis has spent the last few decades looking for long-forgotten songs that soundtracked his youth. He has dedicated himself to rescuing and releasing scores that were once deemed unworthy of standalone releases, reexamining their significance and often unveiling surprisingly contemporary themes that resonate more with today’s audiences than with the era in which they were made. From superb sound quality to graphics and packaging, De Sanctis’ uncompromising attention to detail has become a hallmark of the label that continues to captivate loyal fans nearly a decade after its inception.

Editor’s note

This is a collaborative interview by Tee Cardaci and Fiona MacPherson-Amador, with parts of Tee’s interview being featured in Dust & Grooves Volume 2’s Past to Present: A Roundtable on the Art of the Reissue. This feature of the book includes a discussion with six record labels on what makes a successful reissue, with insight on changing business models and tracking down obscure music. Tee spoke in depth with Pierpaolo about what it is to run a reissue label and the complexities of the quests that come alongside it. Fiona dives deeper into Pierpaolo’s personal collection, exploring what drives him to continue his passion for the vast, yet elusive world of Italian soundtrack and library records and their significance within the genres. Inevitably, the two separate conversations with Tee and Fiona are inextricable, so this is our first joint piece.

"I am a music enthusiast. I am a cinema enthusiast. I jump in the air when I find something that has been considered to be lost forever."

Pierpaolo De Sanctis Tweet

Tee Cardaci: Please introduce yourself, tell us who you are, and where you’re from.

I am Pierpaolo De Sanctis. I am from Rome, Italy, and I run Four Flies Records.

T: If you were to meet someone unfamiliar with Four Flies, how would you sum up what you do?

Four Flies was born in 2015 here in Rome. It all started with the idea of reissuing very rare and underrated Italian soundtracks from the 1960s and 1970s, which are my passion.

T: What was your gateway drug into the deep rabbit hole of Italian library records and soundtracks?

As a kid, I always watched movies on television. We had a lot of little private local television stations that broadcast every kind of film at any time of the day. I watched many strange movies in my childhood: horror, crime films, comedy, and, of course, erotic movies. It’s incredible. You could watch every type of crazy flick at any hour of the day.

While watching these movies, I noticed the colors; the cinematography was really strong, peculiar, and particular. And of course, I fell in love immediately with the music because it wasn’t the kind of music that I could find elsewhere.

I began listening to music on my own from a young age. I loved new wave, post-punk, punk, hard rock, and, of course, ‘60s rock. I had all that music on cassette when I was really young, but I couldn’t find soundtracks to these films on CDs or vinyl. I felt that there was something magic in this music, and I started to search for it and eventually started studying it.

In the late 1990s, when I was eighteen or nineteen, I remember labels in Italy like Right Tempo that produced compilations focused on Italian soundtracks of the 1960s and 1970s that featured jazz-funk, early electronica, psychedelic pop, and freakbeat. All those sounds I only knew from watching those movies. These first compilations I bought showed me an entire world I could discover. This started my passion and also my need to learn more.

"The sound of modernity in Italy came from a manipulation of the American way of life and the inspiration for them was Isaac Hayes."

Pierpaolo De Sanctis Tweet

Fiona MacPherson-Amador: Jay Richford & Gary Stevan’s Feelings was an Italian production that aimed to be received as an international one. You tend to favor Italian composers and films—is this purely because of what you told Tee about growing up with such access to Italian films, or is there something deeper?

On this record I recognized Enrico Pieranunzi’s sound on the Fender Rhodes electric piano in the recording session. He has this unique way of moving faster and faster along the keyboard, like a really fast jazz solo. I then spoke with Enrico, and he told me the real story behind the production of this album.

This was conceived not just as a library album, but as a jazz-funk pop album. Also, the run of the album wasn’t as short as the other library music albums. The producers and main composers of the album, Stefano Torossi and Sandro Brugnolini, worked in the library music field; both of them were musicians, composers, and music consultants for Italian television broadcasting at RAI. They saw that this album was special and very well-produced, even though it was made on a tight budget. They called two arrangers, Puccio Roelens and Giancarlo Gazzani, to work with. Both of them also took part in the composition of every single track of the album, so it was made by four people in the end.

The sound of modernity in Italy came from a manipulation of the American way of life and the inspiration for them was Isaac Hayes, who became famous in Italy in the ‘70s thanks to his 1972 Academy Award winning soundtrack to Shaft. From then on, almost every Italian film music composer tried to make their “blaxploitation” soundtrack at Cinecittà. Torossi and Brugnolini worked to develop the album that was American in sound but in a completely Italian way. This mixture of different things created, for me, one of the best albums in the library music field. This album is repressed every four or five years by different labels and always sells out. It’s a sign that it is timeless and without boundaries.

T: How would you describe the difference between a reissue label and an archive label? Four Flies is a bit of both.

When Four Flies first started in 2015, it was a reissue label because our first releases were reissues of rare ‘70s Italian soundtracks. But very soon, my focus went more to unreleased stuff, unreleased scores specifically, and all the music that remained without any record issued at any other time before.

Italian cinema was a real industry. We produced over 300 movies a year, but just a very, very small fraction of these soundtracks were ever released—maybe five percent or so. Maybe because at the time, composers, publishers, and labels felt that this was only secondary music, as it was only conceived to be synchronized in these films.

I knew there was great music that was only created for these films that were lost in an abandoned warehouse somewhere. This started my search, and soon, Four Flies became more of an archive label than a reissue label.

T: What makes a project worthy of re-releasing?

When I listen to an unreleased tape for the first time, I often feel that the music is more suited for today than for the time that it was recorded. I don’t want to just make a historical album or issue an unreleased soundtrack just so it can be released. I always try to release something that I feel is necessary for contemporary listening. This is a must for me.

F: RCA – Catalogo Di Musiche Per Sonorizzazioni. You say this is “one of the richest library music series of its time.” Why is that?

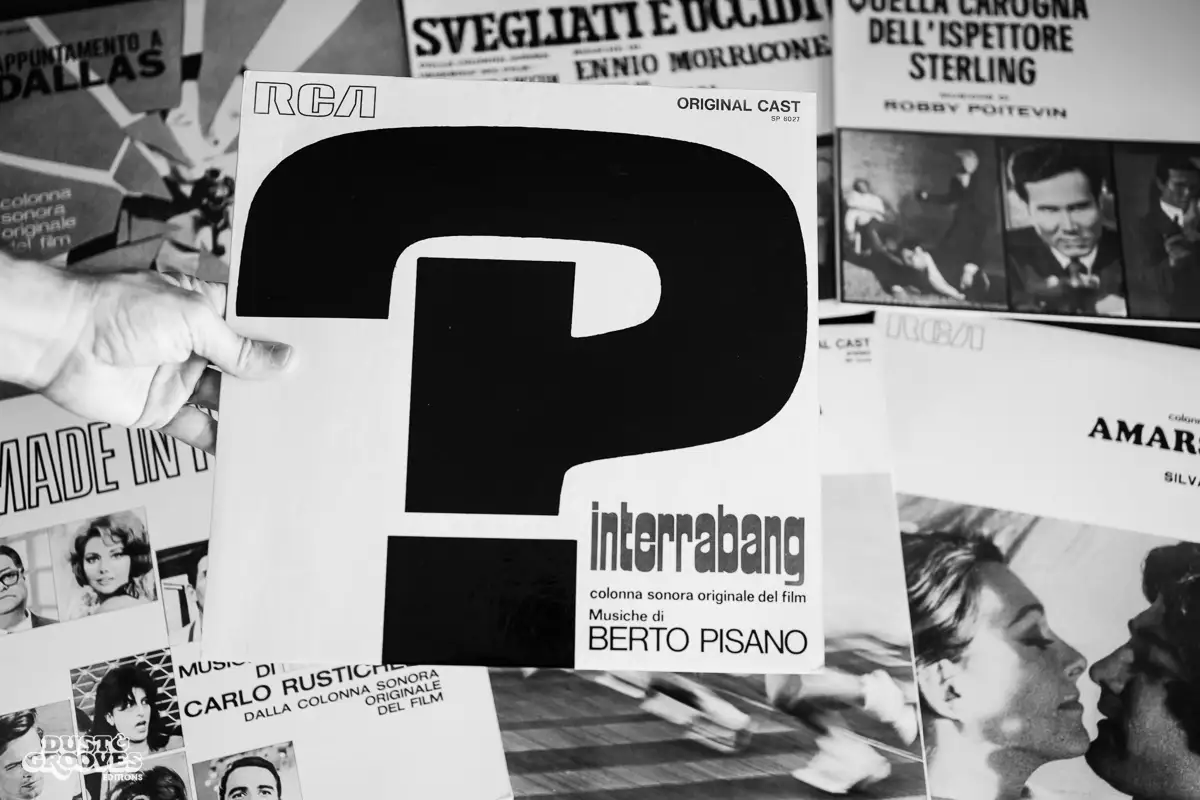

RCA is the same Italian label that produced the original soundtrack for Interrabang. Aside from this, there was also the library series, which was huge because there were more than 100 issues released by them. Very often, these releases were considered to be copies of other soundtracks that were not issued as stand-alone vinyl. These records are so sought after for this reason; the only way to listen to these unreleased soundtracks was to find one of these compilations.

This set of records was gifted to all the radio and television stations to be played, because as a publisher, the more you broadcast your music, the more you earned by PRO and collecting societies—that was the game, the reason why these records were pressed by the publishers. The most beautiful of the series to me are the two volumes of Espressioni Musicali E Suoni D’Attualita’ E Di Moda, because they have some of the best psychedelic rock music from Italy at the time. You can find prog-rock bands like Camel and I Pyranas on them.

The artwork is incredible. It’s a matter of visual identity that pushed me to search for certain records. Maybe this music would be less sought after if it had different artwork. But this one is so psychedelic and fantastic, something that I think makes this music so cool, even today.

“I understand now that my taste, my inspiration, and my suggestions change constantly—from yesterday till tomorrow, they will change again.”

Pierpaolo De Sanctis Tweet

F: Gianni Oddi – “Dreamin’”. You said you fell in love with this on your first listen. How often does this happen? Do you usually need to listen to a record multiple times to love it?

Sometimes, the groove is so strong, so huge that you can’t do anything about it. As you listen for the first time, you recognize this grandeur. But I had some records many years ago that I didn’t appreciate, and I sold them to other collectors. With that money, I bought other records I was more interested in then.

Now, 10 years later, I have completely changed my mind, and I really care about the quality of the record, not just the groove. I understand now that my taste, my inspiration, and my suggestions change constantly—from yesterday till tomorrow, they will change again. Every record, every track, every sound depends on the exact period of your life in which you are living. And now, I’m still looking for the records I sold, and I can’t find them anywhere because it’s not easy to dig up original soundtracks anymore. They’ve become more and more elusive and scarce. It’s okay; that’s a life of a collector.

F: Could you tell me about RCA – Espressioni Musicali E Suoni D’Attualita’ E Di Moda 1? How deep is your love for library music, and does that compare to soundtrack?

First of all, the terms are often confused; people label soundtrack as library music and the other way around. But there are two differences. The soundtrack includes the music composed for a certain film, music that the composer realized and recorded whilst realizing or watching a certain sequence. Library music is a piece of music that is composed and recorded for something that does not yet exist and can be used for any purpose. It is more like a concept album that centers around a theme, like underwater or space ambients. Each album of library music is strongly themed and characterized by an identity.

In terms of collecting, these two worlds are really close to each other because all of these records were out of commerce or printed in a very small run. The only way to receive them was to be a journalist or to work at a TV or radio station as a programmer or music consultant. They got this music because it was part of their work. It had nothing to do with collecting or a passion for music. They issued 200 to 300 copies of the records to ensure that music was synced to the screen to receive money from the broadcasters.

It was repetitive work because the musicians and the composers were like workers in a plant. Their work was very ordinary to them. But after so many years, we recognize that there is incredibly unique music behind these constraints. You could not find this sound in more popular music like jazz, funk, and soul. Library music embraces all the other genres in a new musical experience.

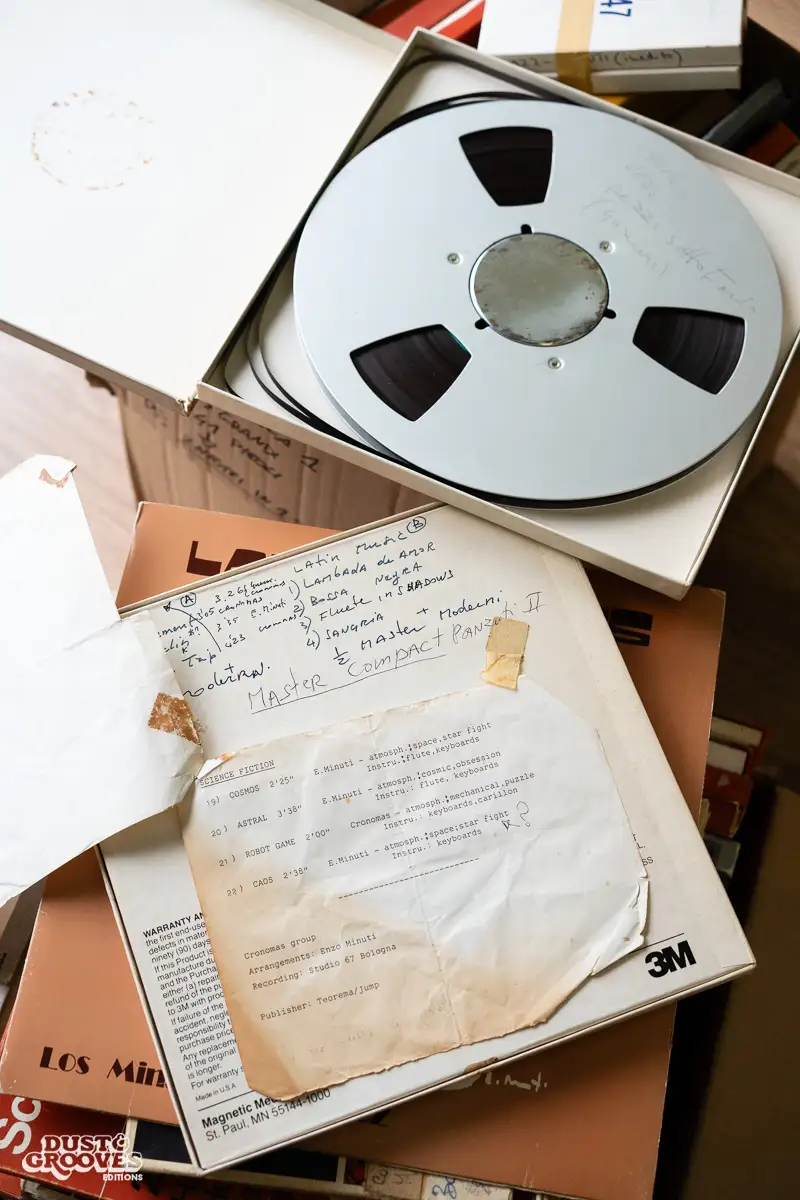

T: Your work includes so many different facets. Which parts of the process do you find the most exciting?

I’m excited when I put my hands on a lost master tape for the first time because I feel a connection to time and space. It’s like a time machine. It’s a magic moment for me, a revelation, when music from a film I have long searched for finally comes in front of me. I am a music enthusiast. I am a cinema enthusiast. I jump in the air when I find something that has been considered to be lost forever. I’m talking about Italian soundtracks from great composers like Piero Umiliani, Berto Pisano, Giuliano Sorgini, and Alessandro Alessandroni. Names that are now considered top-tier internationally were underrated and unknown until a few years ago. This is the work of labels like mine, as well as other reissue labels that have done a lot in the last few years to reestablish the reputations of these composers. Today, many more people know there is more than just Ennio Morricone in this game.

“The music is often more beautiful than the film … Even in the worst B-movies, the music was good. The music was always good.”

Pierpaolo De Sanctis Tweet

T: I can imagine the high that you must get when you hold the master tape in your hands for a score previously considered lost forever in time. If that’s what you enjoy the most, what are the most laborious or difficult parts of the process?

Well, maybe the same part! The most difficult part of the process is finding the master tapes. We’re talking about music that doesn’t exist until a master tape appears. You must also know to whom the music belongs because the Italian cinema and television scenes were full of aliases. Once you have worked out who owns the master, you talk to that label, and they don’t even really know what they have. I have to tell the licensing manager, “Hey, you have these in your catalog! This is a real gem. Please allow me to pay for the license to press this!” It can be hard to convince major labels to grant the license, because it’s kind of time-consuming to answer all these requests from little labels around the world.

T: The visual aesthetic of your label is very strong, and the images you select to accompany each record require a great deal of thought. Speak to this process of sourcing these images and how important it is to you in the grand scheme of a release.

When you are talking about soundtracks, the visual part is a strong component of the product. I always try to take care of every little detail. When talking with the graphic designers, I am not afraid to let them know if the artwork does not work. I’ll ask them to do it again and again until everybody is happy.

Sometimes, we decide to make new art for an old record that was originally released with poor artwork. Many records were conceived as library records that were aimed only at the producers of TV programs, not to the public. I try to consider this and make something that works for the contemporary taste. So, it’s a link between the present and past. Sometimes, the real library aficionados don’t like these new versions. It’s part of the game, and I’m happy to make new artwork when I feel it needs to be done.

T: For the 7-inch you released from the film Un Uomo Dalla Pelle Dura, you went as far as to source imagery from the Spanish poster for the film. Tell us about that.

In the case of Un Uomo Dalla Pelle Dura, which in English was called The Boxer, we used the art from a Spanish poster, which was super rare and nearly impossible to find. But we did, and it worked for the cover we had in mind and was much better than the Italian poster, in my opinion.

F: With soundtracks, especially more than commercial records, is it ever possible to separate the music from the image?

A few years ago, I would have said, “No, soundtrack music can’t be independent from the images for which it was conceived.” Now that I have a bit more experience, I can say that the music is often more beautiful than the film. The films were often B-movies, and I grew up with B-movies, but you have to admit that not all of them are good [laughs]. But even in the worst B-movie, the music was good. The music was always good. This is something that happened only in Italy, in my experience.

Even though the films themselves didn’t have big budgets, the amount allocated for the soundtrack recording was often very generous. This was because each soundtrack required an orchestra, many session musicians, vocalists, string sessions, and so on. The composers could be honest, experimental, and enjoy making music—and even when they had budget constraints, they were always free to experiment without particular boundaries, and to experiment with their creativity. This happened a lot in Italian film music during the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s.

When there was a budget for a composer, they could find new techniques, and electronics were used creatively. Today, many soundtracks use electronics creatively, and when you listen now, you can recognize that it is avant-garde music that really came before its time. It’s like listening to Aphex Twin 20 years before his existence. I want to share with the world a compilation of electronic film scores because I want people to know we were pioneers in the soundtrack field. At the moment, that remains an ambition.

T: When you begin a new project, are there common steps you take from start to finish? Tell us how you outline your projects.

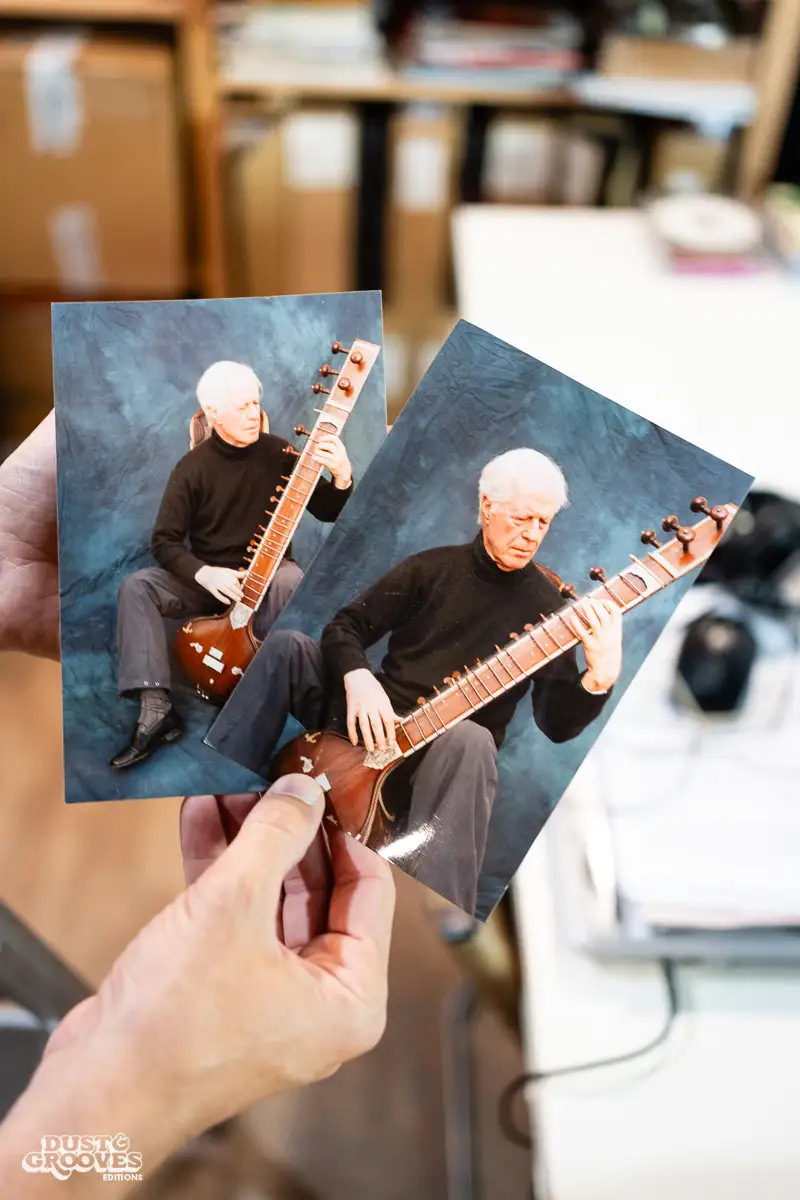

Let’s take the case of the Enzo Minuti record, Music On Canvas. This is a compilation of music from a really underrated composer, and he’s so fascinating because he was a painter as well. He designed all the covers for his records.

Enzo founded the first studio in the city in Bologna, Studio 67, and recorded in his studio with his own instruments. He had this auto-da-fe, a do-it-yourself personality that I think was very fascinating. We could do this compilation thanks to the relationship we had with the family–I knew Enzo’s daughter personally. She gave us a lot of master tapes. She had no idea what was there until we transferred all the master tapes to the studio. It was difficult because of the condition that some of these tapes were lacking due to humidity and time,

We found lots of crazy stuff because Enzo was talented and had a unique and personal style: a mixture of exotica, easy listening, and psychedelic funk. From that point, it was quite easy to decide which tracks to include on the album.

“When you enter the world of soundtracks, it’s not just a matter of music, it’s a matter of aesthetics. There is an entire sensory imagination that is present in a movie.”

Pierpaolo De Sanctis Tweet

T: What if you hadn’t been able to find some of those rights holders? Does the project still go ahead? Explain in deeper detail how payment works if the original rights holder can’t be located.

I can’t tell you the name of this one company, but in one case, it took me six years to get the license. I was crazy about the tracks, and I tried and tried and tried again with different people at this major label before we finally managed to get the license. If we can’t find the original rights holders, we will not release a project. But I would add to that, sometimes we thought we found the proper rights holder and then it comes out that it wasn’t true. Sometimes, a composer’s estate doesn’t have a clear understanding of who actually owns the rights. It can be a mess.

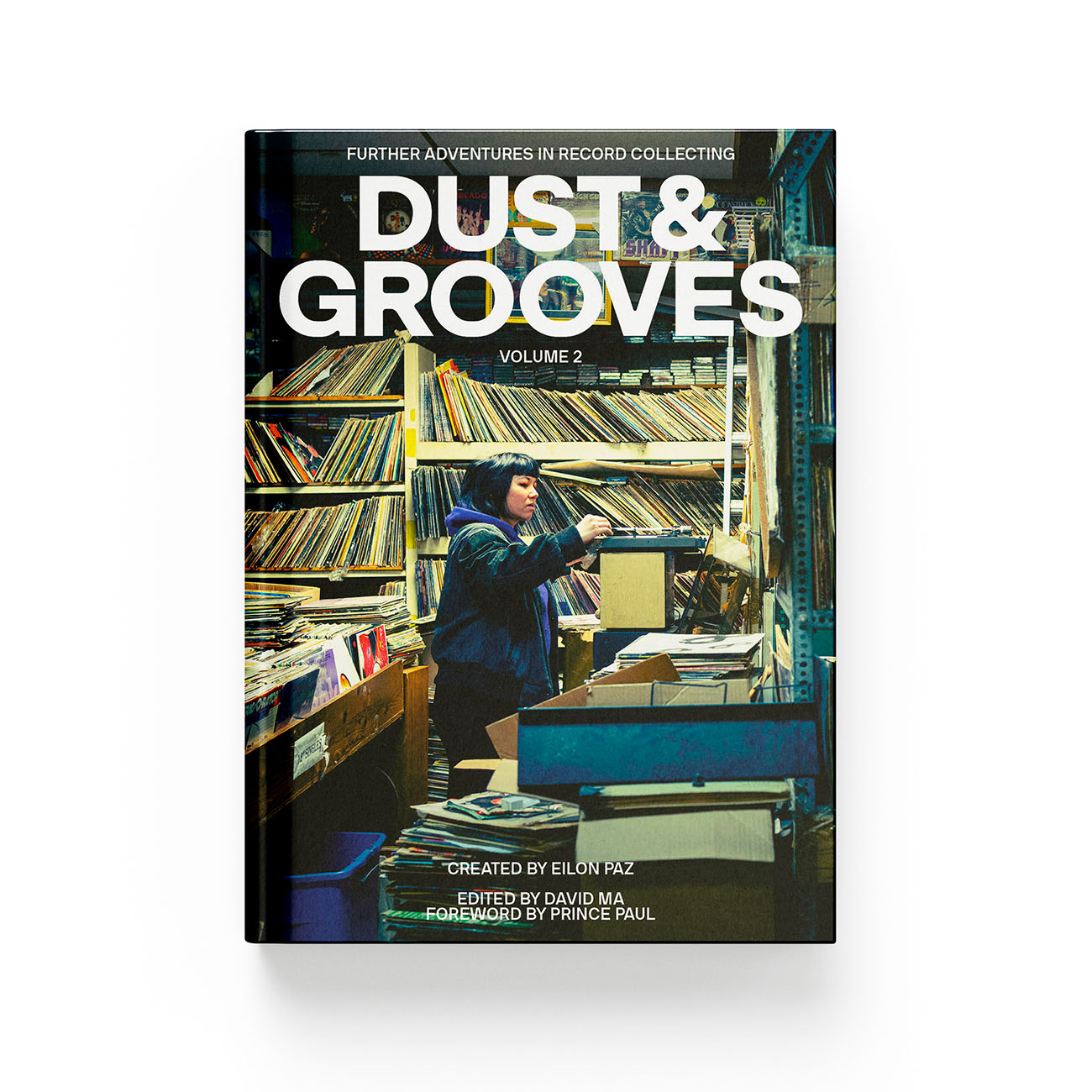

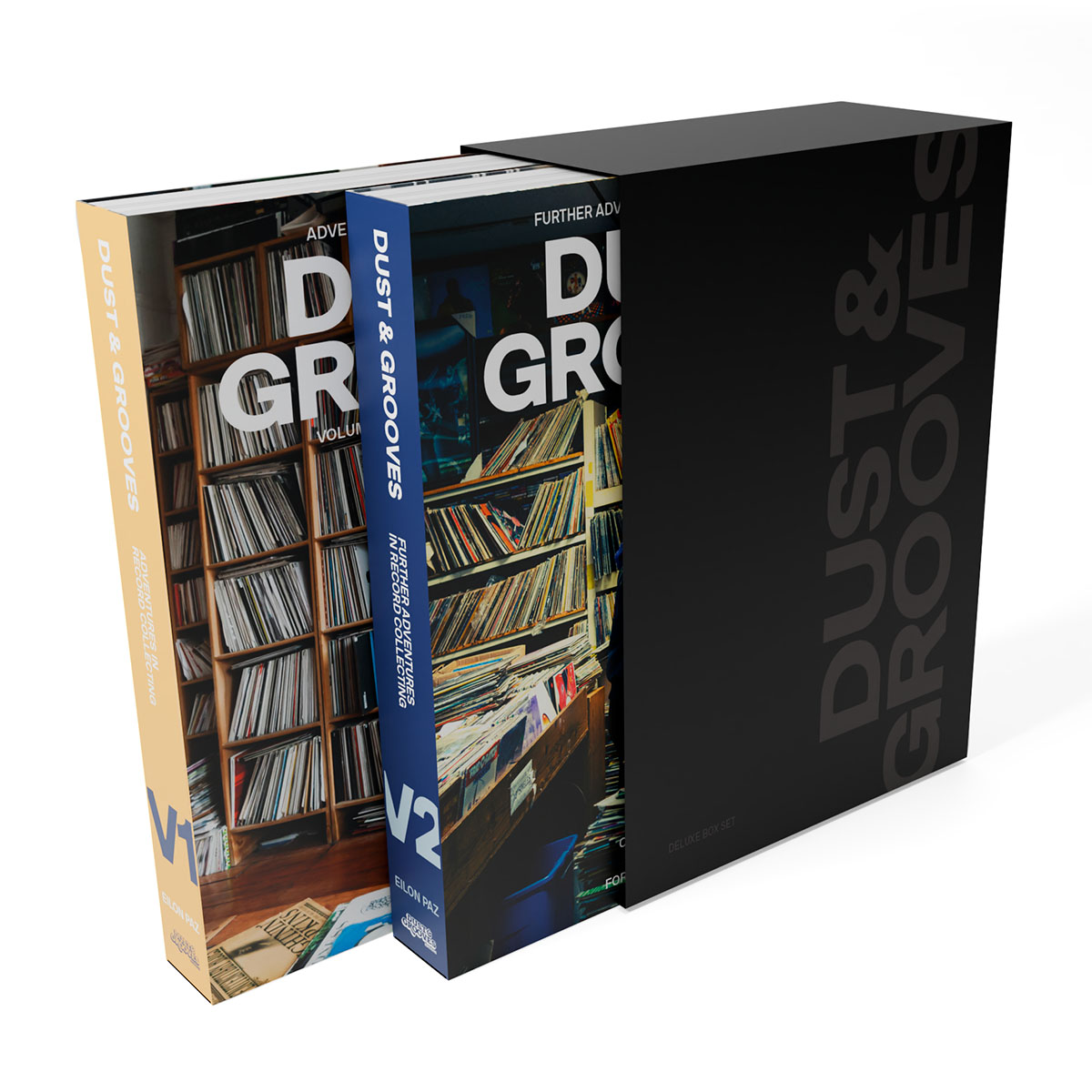

Dust & Grooves: Further Adventures in Record Collecting – Deluxe Slipcase First Limited Edition

Further Adventures in Record Collecting

Dust & Grooves Vol. 2

Pierpaolo De Sanctis and 150 other collectors are featured in the book Dust & Grooves Vol 2: Further Adventures in Record Collecting.

T: A good number of these artists have long since passed away. What’s the reaction when you come across an artist that’s still living?

Most of the time, they say, “You’re wasting your time.”

T: Do you think reissues can be a viable source of income for those artists who are alive but not the rights holders of their work?

In a secondary way, perhaps. I think that even if you are a composer who doesn’t have the rights to your masters, if a label reissues your work and continues to reissue it, you as a composer gain new visibility and maybe new opportunities.

“If a label does not hold the rights to a project, you're dealing with bootleggers…if you don't have the rights, you shouldn’t press the album.”

Pierpaolo De Sanctis Tweet

T: Does the label see any profits if it completes a reissue but does not hold the rights and the project does well?

You’re talking more about bootleggers because if you don’t have the rights, you shouldn’t press the album. I assume the label that presses an album without holding the rights keeps all the income for themselves. I’ve never been in this situation because I don’t press anything if I don’t have the rights. I always try to find the rights holders. Yet I still have so much music that I can’t release because we can’t find the owner of the rights.

T: Speaking of bootlegs, tell me your thoughts on the role of bootleg labels in the reissue field. Are they inevitable, and what do you think the reissue industry would look like without the existence of bootleg labels?

I hate these bootleg labels so much because they diminish our efforts. Maybe we took years to find the rights holders and get the license, and then they took one week to press an album. But in the end, I think that the quality of the product is clear to everyone. People recognize quality and, I hope, will always prefer the quality job done by a reputable label over bootlegs. Some bootlegs I’ve listened to sound horrible, not unlike a bad MP3. Even the quality of the paper used to print the sleeve is not good, and I’ll never buy it.

F: Your copy of Berto Pisano – Interrabang – Colonna Sonora Originale Del Film. This wasn’t for sale and not a commercial release; how did this come into your possession?

This is one of the rarest Italian soundtrack albums from the ‘60s, specifically 1969. I had luck on my side. As a collector, there are two ways of building your collection; one is luck, the other is money. As I don’t have so much money, I have to pray for luck every day [laughs].

One time, I had the opportunity to buy an entire set of albums from Italian RCA, with all the original soundtracks. This series was beautiful and very stylish because it had black and white stills taken from the movies,and the artwork was just stunning. When you enter the world of soundtracks, it’s not just a matter of music, it’s a matter of aesthetics. There is an entire sensory imagination that is present in a movie; it’s music plus visual identity; every vinyl is also a picture—a piece of art. I am attracted to these vinyls because they are pieces of art that reconnect me to the time that the music and film came out. It’s a time machine. When you hold one of these records, you are holding a piece of history, a piece of Italy, a piece of that time.

“As a collector, there are two ways of building your collection; one is luck, the other is money.”

Pierpaolo De Sanctis Tweet

F: Peppino De Luca E I Marc 4 – L’Uomo Dagli Occhi Di Ghiaccio (Man With Icy Eyes) is a crime film soundtrack that contains a lot of what you call “killer jazz numbers.” How much does genre in film and music align? Is there a formula that matches the genre of music to film?

First of all, I am completely in love with this kind of soundtrack, Italian crime soundtracks, because the composers and the musicians who recorded the instruments in these sessions often found a way to create a sound that was, maybe simple, but really cool; it was fresh and modern for the time. In this soundtrack, the backing band was Marc 4, who played for hundreds of soundtracks and library albums in the ‘60s and ‘70s, and they were fantastic. They were the Beatles of library music and soundtrack because they played jazz like they were a pop group. This created a strange mix of things, resulting in a very fresh sound.

This soundtrack is full of funk numbers that feature the vocals of Edda Dell’Orso—she is still alive, she just entered her 90s, and she was the favorite voice of Ennio Morricone. She also worked with every other composer at the time; she was everywhere. This is one of the best because you have Edda Dell’Orso on vocals, Marc 4 as the backing band, including Antonello Vannucchi playing the keyboards.

"I love the artwork and what it suggests about the movie and music; the same connection between visual art and sound made me a music and cinema enthusiast."

Pierpaolo De Sanctis Tweet

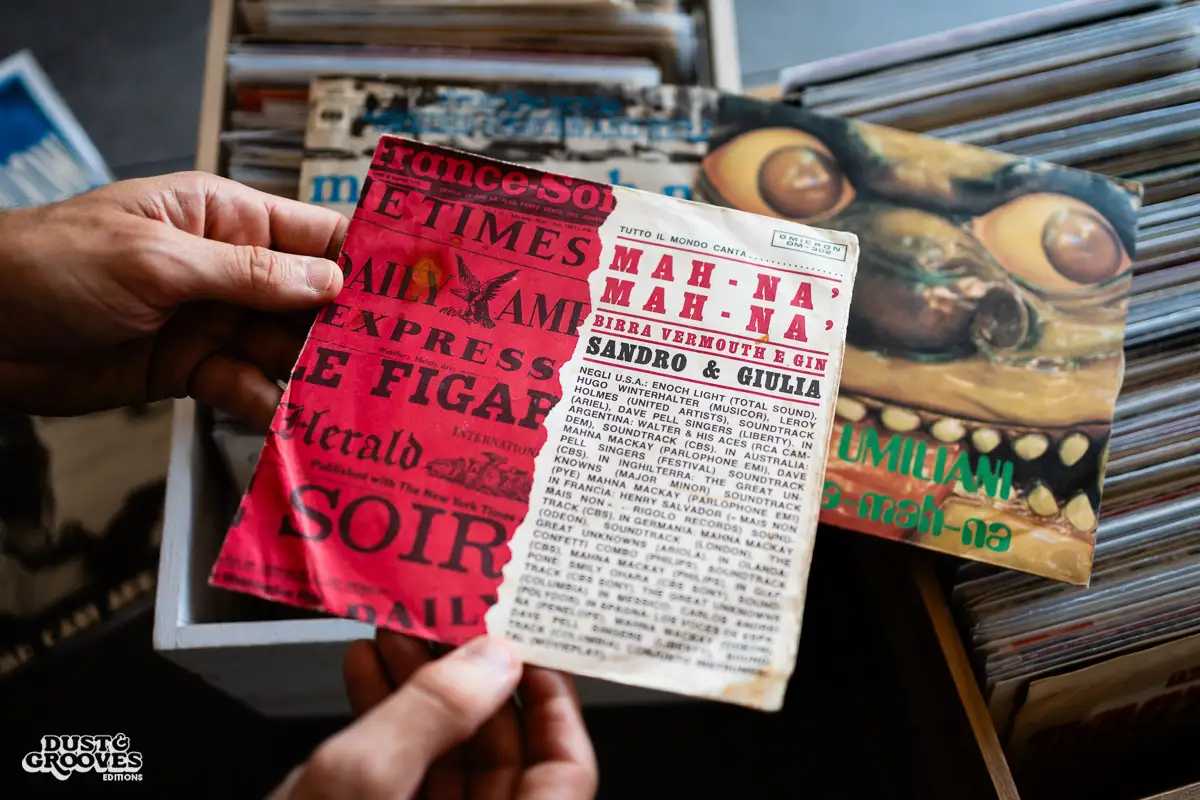

F: You said earlier that Umiliani is one of the greats. Your edition of “Mah-Na Mah-Na’” is one of the only ones that credits his wife, Giulia De Mutiis, and Sandro Alessandroni. Is anonymity and a lack of credits a problem that is often found within library music?

Yes, it’s a mess. For us to study these albums, we always ask ourselves, “Who the hell played bass? Who the hell played the guitar? Who the hell played the drums?” So, we started to train our ears to recognize the sound of all the instrumentalists. We would talk amongst friends who worked as music consultants or publishers to share information from our research. We learned the sound of Enzo Restuccia, the drummer who played for Ennio Morricone soundtracks in the 1970s.

After so many listening sessions, we were able to recognize the differences between individual musicians, and it means that when we work in various roles on labels, we can credit the real names of these musicians. It completes the history behind the making of these totally obscure albums because, at the time, 95% of these albums were issued without any kind of credits regarding the musicians.

The only names credited were the ones regarding the choir. I Cantori Moderni di Alessandroni, for example, was a choir that worked a lot in the Italian industry, including pop music, soundtrack music, and library music. The other choir that was created by Nora Orlandi was called I 4 + 4 di Nora Orlandi.

It’s also great when I recognize an electric or regular piano played by Enrico Pieranunzi. Enrico Pieranunzi is an Italian jazz piano player who is very famous and now very well known. When he was young, he started by playing piano for soundtrack recording sessions. I met him a few years ago, and I told him, “Hey, I listened to the work at the start of your career in Ennio Morricone soundtracks, and you played the piano.” and he replied, “Oh, wow. Was it me? Really?” He recalled the beginnings of his career, and we had a great time discussing his work. He played piano for all the maestros in the ‘70s: Piero Umiliani, Piero Piccioni, Carlo Savina, and Stelvio Cipriani. It was really fun to discover this aspect that was completely unknown at the time.

T: Is there one project in particular that you feel is your high point? One that stands out to you as the closest you’ve come to perfection?

It’s difficult to pick one, but I’ve had some favorites over the years. In the early years of Four Flies, there was the Sortilegio LP, a soundtrack to a movie from 1974 that was completely lost. The film was never released, and only the tape to the soundtrack survived. When I first listened to this music, I went crazy because it was so beautiful, so modern, and filled with great instrumentation. There were influences from everything from jazz-funk to horror soundtracks. That soundtrack sold out in one month, and I was very happy.I met the composer, Silvano D’Auria. He barely remembered working on this project because the film studio went bust, and the movie was never released. He was so surprised that his music had survived and that I was able to find and rescue his work. He thought it was lost forever along with the film.

F: What are your lasting impressions of being a collector?

This search for Italian soundtracks and library music is something—I don’t know if I have to even say this—that keeps you alive. Of course, life is made up of many things that are more important than record collecting, to me at least, but I keep searching for these rare records.

When I find some record that I’ve been searching for for 20 years, it’s always a joy. It’s cool, and it really is a part of my identity as a person. I guess it’s a pathological deviance when you spend money on it, but I maintain that I follow the path of luck more.

T: What’s your grail project? One you’re chasing unsuccessfully?

For many years, the most important one to me has been Ennio Morricone’s lost soundtrack to Danger: Diabolik, a 1968 film based on the Italian comic strip character. It’s really psychedelic but also a bit avant-garde jazz. For many years, I have been trying to track down this soundtrack, but I haven’t been able to find anything. I even asked Morricone himself, but I never got an answer. There are a lot of bootlegs on the market, with audio sourced from the film, so they sound terrible. This is my most wanted tape, but there are also so many more.

F: Who would you like to see next on Dust & Grooves?

I think the world of collectors has been discovered well by Eilon, but I’m curious to know more about some music industry insiders. I’d like more insights from extraordinary labels like Mr. Bongo, Soundway Records or Analog Africa. They are incredible. It would also be interesting to have a musician’s insight. I’m curious to enter their heads and what their inspirations are. It would be nice also to share these secrets because you go to the collectors and labels, but it could also be good to go directly to the musicians who play really good music.

Pierpaolo De Sanctis is an Italian DJ, music consultant and the founder of Four Flies Records, an independent music label dedicated to reissuing Italian golden age soundtracks.

Further Adventures in Record Collecting

Dust & Grooves Vol. 2

Pierpaolo De Sanctis and 150 other collectors are featured in the book Dust & Grooves Vol 2: Further Adventures in Record Collecting.

Become a member or make a donation

Support Dust & Grooves

Dear Dust & Groovers,

For over a decade, we’ve been dedicated to bringing you the stories, collections, and passion of vinyl record collectors from around the world. We’ve built a community that celebrates the art of record collecting and the love of music. We rely on the support of our readers and fellow music lovers like YOU!

If you enjoy our content and believe in our mission, please consider becoming a paid member or make a one time donation. Your support helps us continue to share these stories and preserve the culture we all cherish.

Thank you for being part of this incredible journey.

Groove on,

Eilon Paz and the Dust & Grooves team